Alec Kupelian is the operations and program development specialist at Teen Cancer America. Alec uses his own experience as a cancer survivor to help hospitals across the country develop comprehensive adolescent and young adult programs to treat the person with cancer and not just the cancer. When he’s not working, Alec loves to get outside to enjoy nature or dive into a good game of Dungeons & Dragons. View Alec’s disclosures.

I never finished my freshman year of college. Instead, I was diagnosed with cancer.

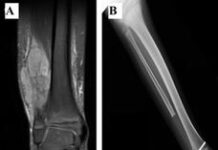

The very next day after receiving my diagnosis, I drove back to my college and packed up all my things, told my new friends I was leaving, and moved out. My tumor was so large that I had to start treatment as quickly as possible. The turnaround time from diagnosis to treatment was 1 day for me. I had 1 day to say goodbye to the life I had just established for myself and move back in with my parents.

I spent the next 11 months in and out of the hospital receiving the treatment that would save my life. People kept telling me how much my perspective on life must have changed and how much of an inspiration I was to go through this. The truth was that I didn’t walk away from cancer with a new outlook on life and the wisdom to inspire millions. I just felt lonely.

I don’t blame my friends for that loneliness at all. They made a huge effort to text, call, and visit me. But that sense of connection wasn’t enough to cover the days on end I would spend in the hospital hooked up to an intravenous (IV) pole doing nothing but watching TV and throwing up. It didn’t cover hearing about their stories at college and wishing I could’ve been there. I didn’t get to be a part of those stories they told me about.

Once my treatment was over and I was able to go back to college, my friends were no longer in my classes and they had new friends, new inside jokes, and a whole year’s worth of memories I had missed. At the time, I didn’t even know I was depressed. I started drinking heavily to cope but, even then, it wasn’t until my first suicide attempt that I sought professional help.

My friends didn’t know what I went through, and I didn’t have the understanding or the language to be able to explain it to them. I didn’t have a good understanding of that loneliness until 7 years after my cancer diagnosis, when I got a job at Teen Cancer America. Working in the field of adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer for the past 4 years has given me a greater understanding of what it means to be an AYA person with cancer because I am connected to people around the country who are just like me.

There are so many things I wish I could’ve told myself when I was diagnosed with cancer and was struggling with loneliness. But since I can’t tell me, let me tell you instead.

1: Ask your health team to provide you with a patient needs assessment every 1 to 3 months.

What I needed throughout the course of my cancer treatment and survivorship changed. I was constantly comparing myself to where I was at before my diagnosis, and I still do, but I’m working on it. I wanted a structured routine more than anything. So even when I needed something to change, I clung to my old habits for fear of that very change. It was a reaction that remained throughout treatment and onward into survivorship.

Often, there is this sense that once treatment is over, you’ll be fine. But the reality is, you just went from the rigid structure of treatment back into the wide world without a safety net. Cancer doesn’t end when treatment does, so your care shouldn’t either. By receiving a regular patient needs assessment, your health care team can help you identify which of your needs aren’t being met and work with you to meet those needs.

2: Seek professional mental health counseling on a consistent schedule throughout treatment and beyond.

The reality is that when my health care team first introduced me to psychological services, I didn’t have the mental capacity to think about going to another appointment. I was still trying to survive, so I wasn’t yet ready to engage with the process of healing. That changed for me partway through treatment, but I still didn’t reach out to a therapist until almost 2 years later. It was almost too late for me. Don’t follow my example.

3: Go to a support group once, even if you think you don’t want to.

Look, I think the term “support group” is stupid. Not because it is actually stupid, but because the connotation around the word makes it sound like you have to really need help to go. Rather, what a support group really entails is just a bunch of other people hanging out who are like you and who are going through something similar. You don’t even have to talk about cancer if you don’t want to. But these are the people who know better than anyone what you’re going through. Maybe they’re in a different place in their cancer experience, or maybe they have completed more or less of their treatment. But these are all people with cancer just like you. The most common thing I hear from AYA people with cancer after their treatment has ended is that they wish they had gone to a support group.

4: Find regional or national nonprofit organizations that help AYA people with cancer.

There is a whole world of cancer nonprofits waiting to give you a lot of free things and cool experiences. There are groups that do adventure trips specifically for people with cancer, for free. There are groups that do writing, art, or music together, and they often connect you to the professionals in the field, also for free. There are organizations that help you travel to the hospital, help with cancer care costs, or help you with legal and insurance concerns. There are even exercise platforms for people with cancer, all for free. The list goes on and on and on.

5: Give yourself and others some grace, but especially yourself.

The truth is, there are going to be times when cancer and survivorship just sucks. There is nothing you can do, and it just sucks. That’s OK, and it’s normal. There is a lot of pressure to feel like you need to be OK so that your support system doesn’t have to worry about you. But you have to give yourself the permission to not be OK and the patience to suffer. It sounds like weird advice, but I personally think it’s important to acknowledge that healing isn’t linear. Some days are going bad, some days are going to be less bad, and some days are going to be good. So give yourself some grace, because no matter what, you’re doing a good job. I promise.

If you feel you’re in crisis and cannot reach your doctor or a loved one, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing the code “988” (available in the United States).