, by NCI Staff

A form of immunotherapy known as CAR T-cell therapy is increasingly being used to treat some people with the blood cancer non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). To date, however, CAR T-cell therapy is used only after patients have already received several lines of treatment. But it has not been clear whether the use of CAR T-cell therapies earlier in a patient’s course of disease would be more effective against their cancer than the standard treatment of chemotherapy and a stem cell transplant.

New results from three large clinical trials now suggest that, after initial chemotherapy, CAR T-cell therapies may be more effective than standard treatment. These results could herald a change in clinical practice, several researchers said, with CAR T-cell therapies being used earlier in the course of disease.

All three studies involved patients with aggressive B-cell NHL, the most common form of NHL, whose cancer had returned early or gotten worse following their initial treatment.

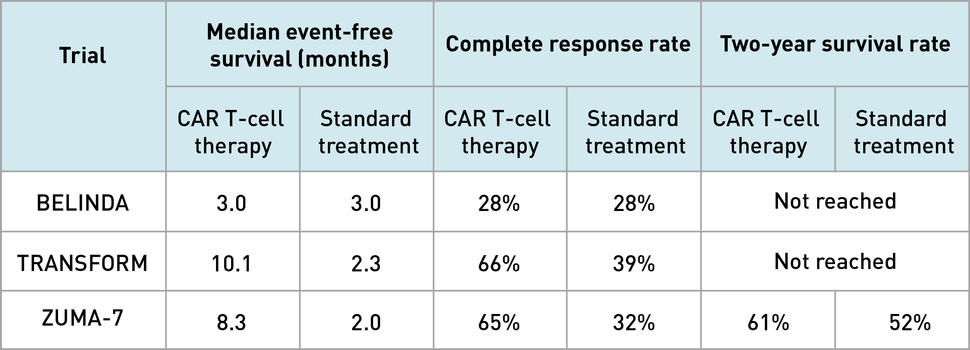

In two of three trials—called ZUMA-7 and TRANSFORM—patients who received CAR T-cell therapy after just one round of chemotherapy lived longer without their disease progressing than patients who underwent the standard treatment approach. That approach usually involves additional, or “salvage,” chemotherapy, followed by a stem cell transplant.

The third trial, called BELINDA, however, found no difference in how long patients lived without their cancer getting worse regardless of whether they were treated with CAR T-cell therapy or the standard approach.

In an interim analysis of data from the ZUMA-7 trial, the researchers estimated that more patients treated with CAR T-cell therapy were alive after 2 years than those who received the standard treatment. In the BELINDA and TRANSFORM trials, it was too early to determine whether there was a difference in how long patients lived overall.

Each trial used a different type of CAR T-cell therapy. ZUMA-7 used axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta), TRANSFORM used lisocabtagene maraleucel (Breyanzi), and BELINDA used tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah).

Results from all three trials were presented at the American Society of Hematology (ASH) annual meeting, which took place from December 11 to 14, 2021. Results from ZUMA-7 and BELINDA were published December 11 and 14, 2021, respectively, in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). Results from TRANSFORM are available in an ASH meeting abstract.

It is unclear whether the conflicting results from the BELINDA study mean that tisagenlecleucel is less effective than the other two CAR T-cell therapies tested, said lymphoma specialist Christopher Melani, M.D., of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research, who was not involved in any of the trials.

There were key differences in how each trial was conducted and the patients included in each study which may have affected the results, Dr. Melani explained. So, without a head-to-head study comparing the CAR T-cell therapies against each other, “I don’t think we’re going to know,” he said.

Nonetheless, two of the three trials show that CAR T-cell therapies are “more effective than salvage chemotherapy and an autologous stem cell transplant,” Dr. Melani said.

“I think the results [from the ZUMA-7 and TRANSFORM trials] are really quite remarkable,” said Laurie Sehn, M.D., a lymphoma specialist at the University of British Columbia Faculty of Medicine, during an ASH press briefing on the studies. “I think it’s inevitable that [CAR T-cell therapies] will become the standard of care” for second-line treatment of patients with aggressive NHL.

Which therapy is best for treating chemo-resistant NHL?

For patients with aggressive B-cell NHL, the standard first-line treatment is chemotherapy. “[First-line] chemotherapy will cure approximately 70% of patients overall,” Dr. Melani said.

But for the 30% of patients whose cancer doesn’t respond to chemotherapy, or returns after initially responding, outcomes are uncertain at best. The standard second-line treatment often begins with salvage chemotherapy.

“Most [salvage chemotherapy regimens] will have some effect in upwards of half of people with aggressive B-cell NHL, but salvage chemotherapy alone usually does not lead to long-lasting remission,” said Dr. Melani.

Patients who do respond to salvage chemotherapy typically go on to receive a stem cell transplant if they are healthy enough to undergo one.

But “more than half of patients [receiving salvage chemotherapy] will not receive a transplant,” said Michael Bishop, M.D., of the University of Chicago’s David and Etta Jonas Center for Cellular Therapy, the lead researcher of the BELINDA trial. If patients don’t respond adequately to salvage chemotherapy, they won’t be eligible for a transplant, Dr. Bishop said.

Although this sequence of treatments cures some patients, it only leads to long-lasting remissions in less than 20% of patients who receive it.

At the same time, CAR T-cell therapies used after two or more prior treatments have had impressive results. “We are likely curing somewhere between 35% and 40%” of people with relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell NHL with CAR T-cell therapy after salvage chemotherapy has failed, Dr. Melani said.

So, researchers wondered whether CAR T-cell therapies could be used not just after salvage chemotherapy and a stem cell transplant, but as second-line treatment in place of these other treatments.

ZUMA-7, TRANSFORM, and BELINDA: Similarities and differences

The three studies presented at the ASH meeting were all phase 3 clinical trials that compared CAR T-cell therapy with the standard of care in people whose B-cell NHL had come back after initial treatment.

ZUMA-7 was funded by Kite Pharma, TRANSFORM by Celgene, and BELINDA by Novartis Pharmaceuticals—the respective manufacturers of the CAR T-cell therapies studied in each trial.

The ZUMA-7 trial, which evaluated axicabtagene, enrolled 359 patients. TRANSFORM, which tested lisocabtagene, enrolled 184. And the tisagenleucel study, BELINDA, enrolled 322 patients.

After enrollment, patients were randomly assigned to receive either the CAR T-cell therapy or salvage chemotherapy. If possible, patients in the salvage chemotherapy group went on to receive a stem cell transplant.

In all three trials, researchers measured the length of time between a patient’s enrollment and when important “events” occur, such as disease progression, death, or beginning a new treatment. This measure is called event-free survival.

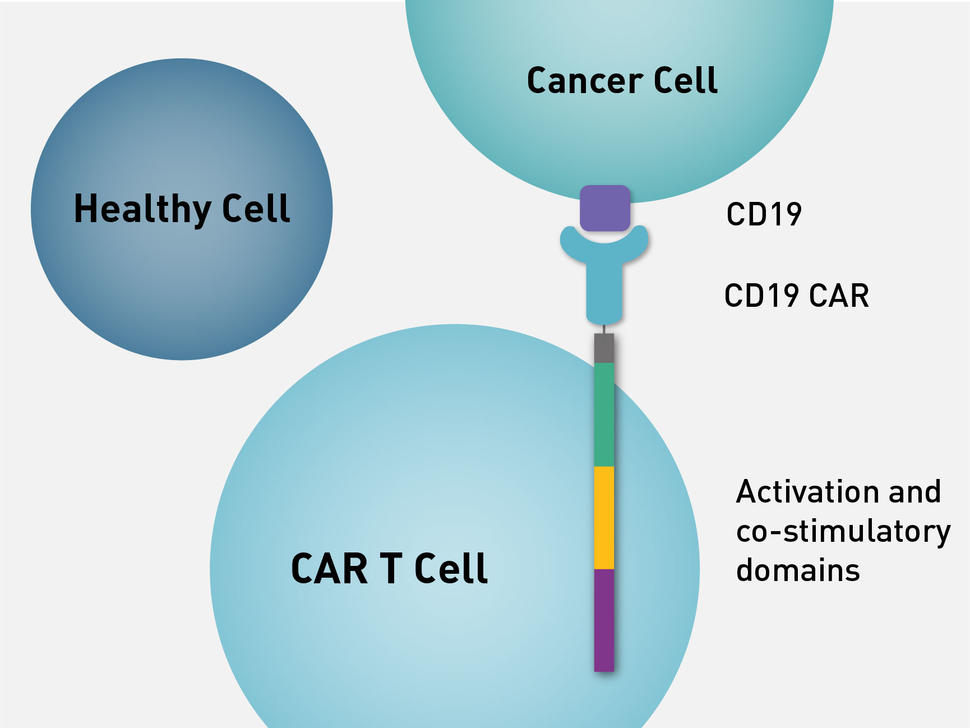

Like all CAR T-cell therapies, each of the three therapies tested are produced by a complex manufacturing process, in which the gene for an engineered protein called a chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR, is added to patient’s T cells to help them better attack cancer.

Although they share many features, the three CAR T-cell therapies used in the trials have some important differences, including in the “costimulatory” portion of the chimeric antigen receptor. The costimulatory domain is essential for full T cell activity. The method by which a patient’s T cells are genetically engineered also differs between the therapies.

Another difference was in the use of “bridging” chemotherapy that some patients who receive CAR T-cell therapies undergo to slow disease progression while the CAR T cells are being manufactured. The length of the manufacturing process can vary, but usually takes at least 2 weeks.

Whereas BELINDA allowed for multiple rounds of bridging chemotherapy, TRANSFORM allowed for only a single round, and ZUMA-7 did not allow for any bridging chemotherapy. Allowing bridging chemotherapy could affect the patient population of a trial, since sicker patients can be included in trials that use bridging.

In ZUMA-7 and TRANSFORM, patients randomly assigned to receive CAR T-cell therapy had longer event-free survival than those randomly assigned to receive the standard treatment of salvage chemotherapy plus a stem cell transplant, if possible. Patients treated with CAR T-cell therapy also were much more likely to have their cancer completely eradicated (a complete response). For patients in the BELINDA trial, however, event-free survival and the complete response rate were the same in both groups.

According to Dr. Sehn, the TRANSFORM and ZUMA-7 results are likely to change patient treatment moving forward. “It’s remarkable that the results are so favorable compared with standard of care,” she said.

But why did BELINDA not show a difference when the other two studies did? In an editorial published in NEJM in response to the BELINDA and ZUMA-7 trials, Mark Roschewski, M.D., of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research, and colleagues noted that because BELINDA allowed for bridging chemotherapy, it may have included more patients with very aggressive disease than ZUMA-7.

Based on previous studies, “it doesn’t seem like tisagenlecleucel should be less effective than the other two” CAR T-cell therapies, Dr. Melani said. Instead, he agreed that the inconsistent results between BELINDA and the two other trials could reflect their different trial designs and patient populations.

Side effects were similar across all three trials and, overall, severe side effects were uncommon.

Cytokine release syndrome (CRS), a common and potentially life-threatening side effect of CAR T-cell treatments, occurred in all three trials. CRS occurred most frequently among ZUMA-7 trial participants, with 92% of patients experiencing CRS but only 6% experiencing severe CRS.

In the BELINDA trial, 61% of patients experienced CRS, while only 5% had severe CRS. In the TRANSFORM trial, about half (49%) of patients had CRS symptoms and only one severe CRS event (1% of patients) was reported.

Optimizing CAR T-cell therapy for NHL

The differing results between these three trials provide interesting possibilities for future research, said Dr. Melani. A study directly comparing CAR T-cell therapies could help resolve whether one therapy is more effective than the other two, for example. At the moment, no such trials are planned.

Additionally, CAR T-cell therapy does not work for all patients, and “we have no effective way to predict who’s going to be cured versus not with CAR T cells,” Dr. Melani said. Further research is needed to identify features of a patient’s disease that makes it particularly susceptible to CAR T-cell therapies, he added.

Based on the results from ZUMA-7 and BELINDA, Dr. Roschewski and his colleagues concluded that patients who can undergo CAR T-cell therapy without bridging chemotherapy should receive CAR T cells as second-line therapy. However, they cautioned, “it is premature to conclude that CAR T-cell therapy is superior for all [stem cell transplant]–eligible patients.”

Dr. Bishop agreed. “I think we need to look at differences between the three trials to try and define which patients benefit the most” from CAR T-cell therapies, Dr. Bishop said during his ASH presentation.