, by NCI Staff

Over the course of several decades, NCI scientists laid extensive groundwork for a novel treatment that would eventually go on to become axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta), a CAR T-cell therapy for adults with lymphoma.

While the therapy can lead to long-lasting remissions for some patients with very advanced cancer, it can also cause neurologic side effects such as speech problems, tremors, delirium, and seizures. Some side effects can be severe or fatal.

So, in 2017, NCI researchers tweaked their original CAR T-cell design with the goal of creating a safer and more effective therapy. Now results from the first clinical trial of the remodeled CAR T cells suggest that they may have achieved part of their goal.

The new therapy caused far fewer neurologic side effects than the original therapy did in an earlier trial, yet it was equally effective. The findings were reported January 20 in Nature Medicine.

“It’s remarkable that out of 20 patients in this trial, only one had severe neurologic side effects,” said associate investigator Jennifer Brudno, M.D., of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research.

“This appears to be a significant advance in our current understanding of how CAR T cells work and how to make a safer CAR T [-cell therapy],” said David Maloney, M.D., Ph.D., medical director of cellular immunotherapy for Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, who was not involved in the study.

However, the study is limited by the small number of patients involved and the relatively short amount of time patients’ outcomes have been tracked, he added.

T Cells Get a New CAR

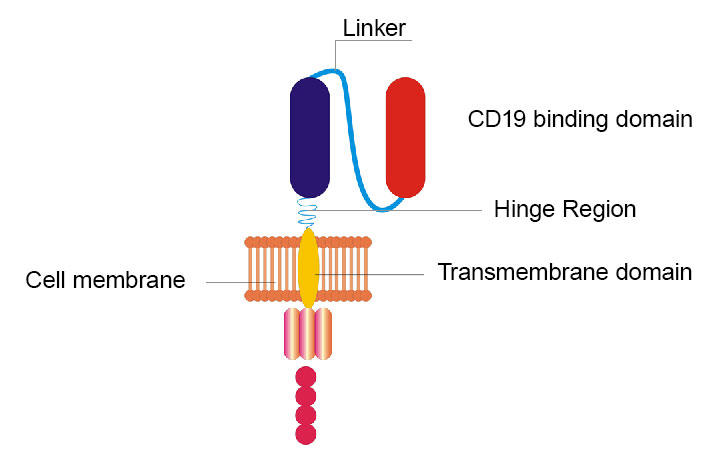

CAR T-cell therapy involves arming a patient’s own T cells (a type of white blood cell) with a specialized protein called a CAR, or chimeric antigen receptor. This receptor helps the T cells find and kill the person’s cancer.

The NCI team’s remodeled CAR is different from the original in a few ways. For instance, two sections (called the hinge and transmembrane domains) of the original CAR were replaced. And another section that originally consisted of a protein fragment found in mice was swapped for a similar fragment found in humans. But, like the original, the new CAR also targets CD19, a molecule that studs the surface of lymphoma cells.

In earlier lab studies, the researchers found that T cells armed with the new CAR slowed the growth of tumors in mice. And compared with the original CAR T cells, the new CAR T cells produced lower levels of substances called cytokines.

Scientists don’t fully understand how CAR T cells cause neurologic side effects, but cytokines may be partially to blame. Cytokines are also the culprit for cytokine release syndrome, another potentially life-threatening side effect of CAR T-cell therapy.

With these promising results, the team moved forward with a first-in-human study of the remodeled CAR T cells.

Fewer Cytokines, Fewer Neurologic Side Effects

In the new trial, Dr. Brudno and her colleagues gave the new CAR T-cell therapy to 20 patients with B-cell lymphoma.

Overall, four patients (20%) experienced some neurologic toxicity: Three had mild effects and one (5%) experienced severe effects that quickly went away after treatment with a steroid (medicine that tamps down the immune system).

In an earlier study of the original CAR T-cell therapy involving 22 people with B-cell lymphoma, 17 (77%) experienced some neurologic toxicity—including 11 patients (50%) who experienced severe symptoms.

Two patients (10%) in the new trial and four (18%) in the earlier trial had severe cytokine release syndrome. “It seems favorable that [the rates are] similar, but it is difficult to say if [cytokine release syndrome] is definitely less frequent” with the new therapy, Dr. Brudno said.

Cytokine levels were lower in the blood of patients treated with the new therapy than in patients who got the original therapy, the scientists found, which might explain why the new therapy caused fewer neurologic side effects, they wrote.

In both trials, the researchers used the same methods to grade the severity of neurologic toxicity and cytokine release syndrome, Dr. Brudno noted.

And although there are other similarities between the two trials—they were conducted at the same facility, for instance—it’s tricky to compare results from independent studies, she said.

CAR T Cells That Stick Around

One issue with current CAR T-cell therapies is that the cells don’t last very long in the patient’s body. That’s partially because the human immune system can see mouse proteins as unfamiliar and destroy the CAR T cells.

Part of the team’s goal was to create CAR T cells that stick around, or persist, longer. They reasoned that T cells with a CAR made of all human proteins might last longer than cells with a CAR containing mouse proteins.

If the patient’s immune system ignores a CAR made of human proteins, then the CAR T cells might last longer and be more effective, Dr. Brudno explained.

That may be the case for the new therapy. A month after receiving the treatment, there were higher levels of CAR T cells in the blood of patients who got the new therapy than in those treated with the original therapy.

These findings are “encouraging” and should be explored in future studies, Dr. Maloney said.

Although the new CAR T cells seem to persist longer than the original CAR T cells, they did not appear to be more effective. In both trials, more than half (55%) of the participants went into complete remission.

But it is “heartening” to see “very good efficacy for this CAR T-cell product, in addition to the low toxicity,” Dr. Brudno said.

An Informative Redesign

CAR T-cell therapy can lead to a diverse array of neurologic effects, ranging from very mild to severe and life-threatening, Dr. Brudno explained.

These side effects are associated with all currently available CAR T-cell therapies—two that are FDA approved and another pending FDA approval—Dr. Maloney noted. In other studies, rates of severe neurologic toxicity have ranged from 5% to 50%.

Other clinical trials are testing CAR T-cell therapies that have also been redesigned to be safer, Dr. Maloney noted. The new NCI study identifies aspects of the CAR T-cell design that weren’t previously known to affect neurologic toxicity, he said.

“But how you translate that into a new commercial product or upgrade [an existing] commercial product is a whole different question,” he said. Manufacturing a CAR T-cell therapy for each individual patient is a complex and expensive process that can only be done at highly specialized facilities.

For now, the NCI team, led by James Kochenderfer, M.D., is focused on conducting clinical trials of different CAR T-cell therapies for people with another type of blood cancer, multiple myeloma.