, by Linda Wang

People with desmoid tumors, an extremely rare and potentially debilitating soft-tissue tumor, may soon have an approved treatment option based on the results of a new clinical trial. This disease currently has no standard treatment options.

At 2 years after starting treatment with the investigational drug nirogacestat, three-quarters of trial participants were alive without their disease getting worse, compared with less than half of patients who were given a placebo.

In addition, treatment with nirogacestat either partially or completely shrank tumors in about 40% of patients, whereas only 8% of patients given a placebo had tumor shrinkage. Patients who received nirogacestat also reported improvements in pain and physical functioning.

Side effects from nirogacestat were generally modest and included diarrhea and rash.

However, three-quarters of women of childbearing age had ovarian dysfunction, which generally resolved after stopping treatment.

The findings were published March 9 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

This is one of the largest studies to date on desmoid tumors, said Mrinal M. Gounder, M.D., of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, who led the study. The results “can potentially lead to the first new drug approved in this ultra-rare disease.”

The manufacturer of nirogacestat, SpringWorks Therapeutics, has submitted an application to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for approval of nirogacestat for the treatment of adults with desmoid tumors. A decision is expected by this summer.

Nirogacestat’s approval would be “a huge step forward” for people with desmoid tumors, said Jeanne Whiting, co-founder of the Desmoid Tumor Research Foundation. “The desmoid tumor journey can be long, arduous, and very painful. If there’s a treatment that will have fewer side effects, it can really ease the journey for the patient.”

A painful disease with no standard of care

An estimated 1,650 people in the United States are diagnosed with desmoid tumors each year. This rare disease mainly affects young people, but people of any age can develop desmoid tumors, also known as aggressive fibromatosis. People with the genetic condition familial adenomatous polyposis are at a particularly high risk of developing desmoid tumors.

Although desmoid tumors are not cancerous because they don’t have the ability to spread, these tumors can grow quickly and invade locally, causing severe pain and disfigurement. In extreme cases, desmoid tumors can lead to nerve damage, bowel perforations, amputations, and other severe complications. The tumors are also likely to come back after treatment, and people with desmoid tumors may become addicted to painkillers.

There is no standard of care for this disease. Surgery and chemotherapy are commonly used, but they typically fail to keep the disease at bay for long.

“In the past, there was very little for patients with desmoid tumors,” said Marlene Portnoy, co-founder of the Desmoid Tumor Research Foundation. “It was basically like taking a target and shooting in the dark. Doctors would say, ‘Let’s try this, or let’s try that. There was little research [on desmoid tumors] and no treatment protocols.”

Over the past decade, however, some progress has been made in developing a targeted therapy for desmoid tumors.

In 2018, Dr. Gounder and his colleagues published results from a large NCI-funded clinical trial showing that the drug sorafenib (Nexavar), a targeted therapy approved for the treatment of advanced kidney, liver, and thyroid cancer, halted the growth of desmoid tumors.

The feasibility of conducting a large, randomized trial paved the way for the phase 3 trial of nirogacestat, Dr. Gounder noted.

“What that study did was show that we can do phase 3 studies in this disease,” he said.

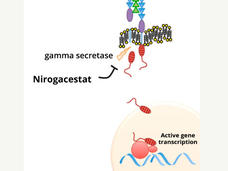

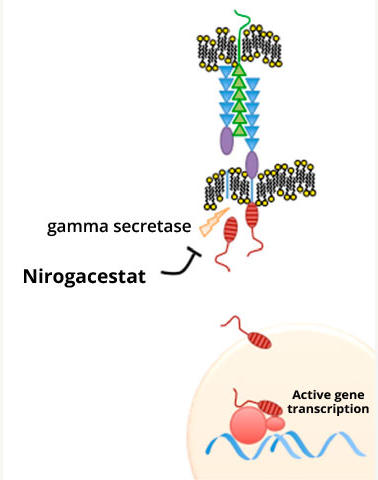

Nirogacestat works by blocking the activity of an enzyme called gamma secretase, which helps activate a signaling protein called Notch. Researchers have hypothesized that desmoid tumors produce high amounts of Notch protein, which is thought to drive their growth.

Nirogacestat was initially developed to treat Alzheimer’s disease, but the drug proved to be ineffective against that disease. However, in clinical trials, nirogacestat showed signs of activity in people with desmoid tumors.

This led NCI to launch a phase 2 study of nirogacestat specifically for desmoid tumors. The trial showed that, after 4 years of treatment with nirogacestat, the disease had not progressed in any of the 17 patients in the study.

The success of that study led SpringWorks Therapeutics—which Pfizer established in 2017 specifically to develop treatments “that hold significant promise for underserved populations,” according to a SpringWorks news release—to launch a phase 3 clinical trial of nirogacestat for adults with desmoid tumors.

Nirogacestat shows effectiveness in shrinking desmoid tumors

The phase 3 trial, called DeFi (for Desmoid Fibromatosis), included 142 adults between the ages of 18 and 76. The participants either had tumors for which they had not received prior treatment, or had tumors that returned after at least one line of treatment, such as chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive either nirogacestat or a placebo orally twice a day. The drugs were taken continuously for 28-day cycles.

After a median of 16 months, people treated with nirogacestat were 71% less likely to have died or had their disease worsen than those treated with a placebo. After 2 years, there was no evidence of tumors getting worse in 76% of people who received nirogacestat, compared with 44% of people who received a placebo.

In addition, 41% of people treated with nirogacestat had tumor shrinkage, compared with 8% of people treated with a placebo. Of those who had tumor shrinkage, tumors were completely eradicated in 7% of people treated with nirogacestat, compared with none in the placebo group.

People treated with nirogacestat also reported reduced pain, improved physical functioning, and improved health-related quality of life.

Side effects were mild and included nausea and fatigue. About 20% of people treated with nirogacestat stopped taking the drug altogether. The only serious side effect was ovarian dysfunction and premature menopause. However, both resolved after participants stopped taking the drug.

Study researchers are now looking more closely at which patients are at greatest risk for ovarian dysfunction, which is not uncommon for gamma secretase inhibitors, Dr. Gounder said.

Promising results, but questions remain

Alice Chen, M.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, who led the phase 2 trial of nirogacestat but was not involved in the phase 3 study, said that the findings are “very significant,” but some questions remain.

For example, nirogacestat’s optimal dose is still unclear, Dr. Chen said, as well as whether patients need to be on the treatment indefinitely or can take a break from treatment after their disease stabilizes.

“Since the tumor doesn’t metastasize, potentially you could follow patients off treatment for a period of time and, when the tumor starts to grow again, consider putting them back on treatment,” Dr. Chen said.

In this young adult population, for example, taking a break from treatment could benefit younger women who are trying to get pregnant, she added.

“We don’t know what the pregnancy consequences [of the drug] are,” she said.

Dr. Gounder pointed out that, even if nirogacestat is approved and becomes the standard of care for people with desmoid tumors, the drug may not be appropriate for every patient.

For some whose tumors are stable and not causing pain or other problems, observation may be warranted, he said. For others, sorafenib, chemotherapy, ablation, or surgery may be a better choice.

And other potential treatment options for desmoid tumors that are already in clinical trials may be on the horizon. For example, a randomized trial of AL102, another gamma secretase inhibitor, is enrolling patients with progressive desmoid tumors.