, by NCI Staff

A new drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is expected to immediately affect the treatment of some men with prostate cancer. In a large clinical trial, the drug, relugolix (Orgovyx), was shown to be more effective at reducing testosterone levels in men with advanced prostate cancer than another commonly used treatment, leuprolide (Lupron).

Treatments that block the production of the hormone testosterone by the testes have been the cornerstone of advanced prostate cancer treatment for several decades. Known as androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), these treatments are akin to putting a stopper in a car’s gas tank: robbing prostate tumors of the fuel they need to grow and spread.

In the clinical trial, relugolix was also much less likely than leuprolide to cause serious heart issues, said Neal Shore, M.D., of the Carolina Urologic Research Center, who led the clinical trial on which the approval was based, called HERO. That’s important, Dr. Shore said, because leuprolide and other ADT drugs have been linked with an increased risk of cardiac events, including heart attacks and heart failure.

“For me, this [approval] is significant,” Dr. Shore said. “Many of the patients we start on testosterone suppression are at risk of having a cardiac complication.”

Given its superior ability to reduce testosterone and safety with regard to heart-related effects, Dr. Shore said, “it’s perfectly arguable” that relugolix should be the preferred choice for ADT in men with advanced prostate cancer.

Alicia Morgans, M.D., who specializes in treating prostate cancer at the Robert H. Lurie Cancer Center of Northwestern University, generally agreed.

“I believe this is a new standard of care for men with [advanced] prostate cancer,” Dr. Morgans said. “It meaningfully and effectively lowered testosterone levels, which is what we manipulate to try to control prostate cancer.”

It may not “necessarily replace every [ADT] option for every patient, but it’s definitely a new standard that appears safe and effective,” she continued, especially for men concerned about any potential heart-related risks.

Going After Testosterone

Prostate cancer that is confined to the prostate is typically treated with surgery or radiation therapy. Once it advances beyond the prostate, either to nearby tissues or to other parts of the body (e.g., bones, liver), ADT is typically used.

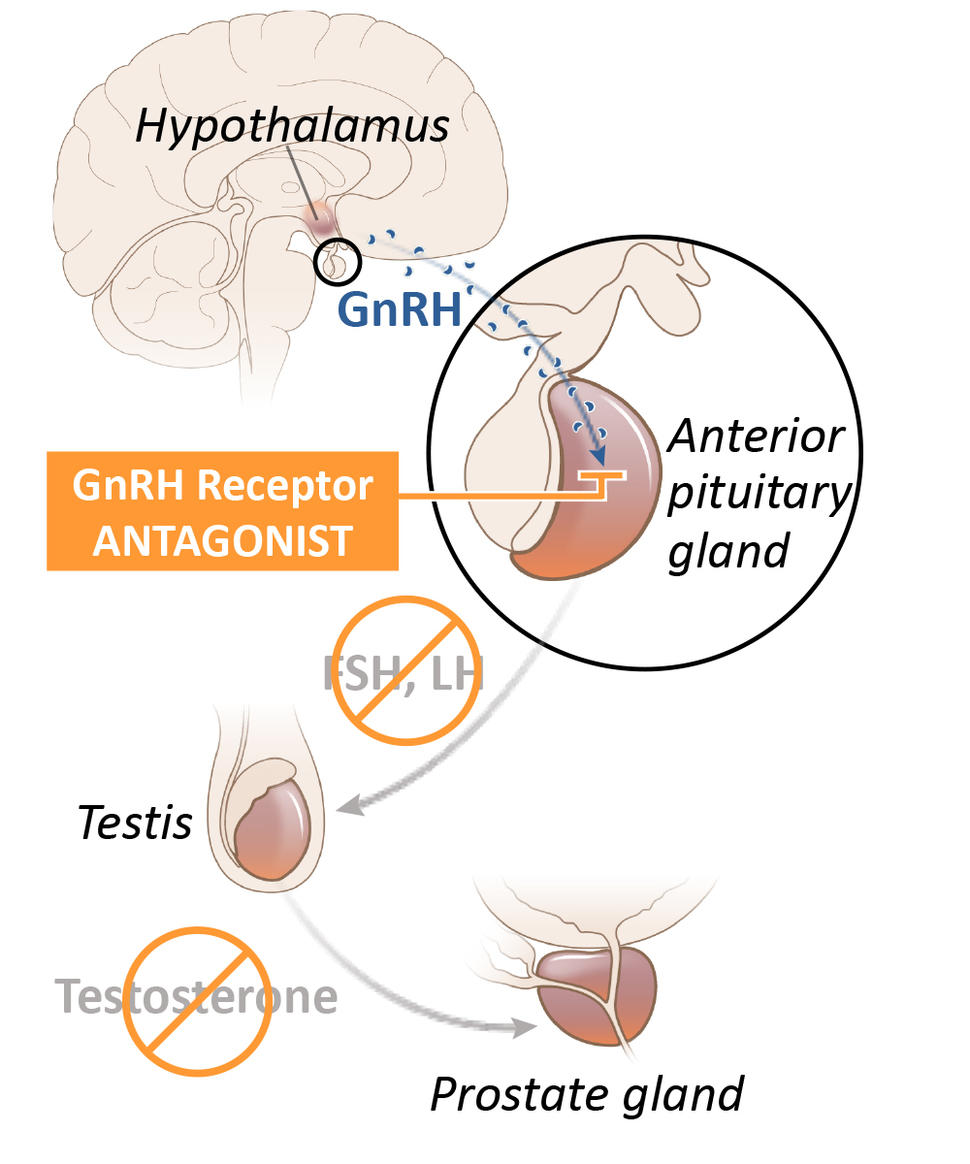

Although several drugs for ADT are available, in the United States leuprolide is the most commonly used option. Known as an LHRH agonist (also called a GnRH agonist), leuprolide acts on the pituitary gland—a tiny organ within the brain that is responsible for producing a hormone that eventually decreases the production of testosterone by the testicles. It is given to patients as an injection into muscle, typically every few months.

Reducing the production of testosterone to very low levels with drugs is often called medical (or chemical) castration, because it achieves the same results as surgical removal of the testes.

Relugolix is known as a GnRH (or LHRH) antagonist. It also acts on the pituitary gland, but in a way that more directly and rapidly blocks testosterone production in the testes. In addition, it is a pill that patients take every day.

ADT “wasn’t necessarily something we thought would be improved upon, because … we’ve had good strategies to lower testosterone with good medications for decades,” Dr. Morgans said. The development of drugs like relugolix is important, she added, because it “took something we’ve been doing forever and tried to make it better.”

Improved Testosterone Suppression, Lower Cardiac Risks

More than 900 men with advanced prostate cancer whose tumors still relied on testosterone (known as hormone-sensitive prostate cancer) were enrolled in the HERO trial, which was funded by Myovant Sciences, the manufacturer of relugolix.

Participants were assigned at random to take relugolix daily for 48 weeks or to receive leuprolide injections every 3 months for the same length of time.

Approximately 97% of men treated with relugolix reached and maintained very low testosterone levels through 48 weeks, compared with 89% of men who received leuprolide. In addition, men in the relugolix group also did substantially better on several other measures, including being able to return to normal testosterone levels within a few months of stopping therapy.

The latter finding is “very important,” Dr. Shore said. Suppressing testosterone for long periods can lead to significant side effects, he explained, including fatigue, hot flashes, and bone problems. And in clinical practice, ADT might only be used for short periods, such as when it’s being given along with radiation therapy.

“So if your testosterone level returns to normal values faster after stopping ADT, that to me is a real positive,” he said.

Side effects were generally similar in both treatment groups, although diarrhea was more common in men treated with relugolix. The biggest difference, though, was the effect on the heart: Twice as many men in the leuprolide group than in the relugolix group (6.2% versus 2.9%) had a “major adverse cardiovascular event,” which included nonfatal heart attack or a stroke.

When the HERO trial investigators looked specifically at men who had a history of heart problems, the difference in the frequency of these cardiac side effects was even more stark: 17.8% in the leuprolide group versus 3.6% in the relugolix group.

The potential heart risks associated with long-term ADT with LHRH agonists such as leuprolide have come into sharper focus over the past decade, Dr. Shore said. In discussions with colleagues who specialize in studying and treating the cardiac effects of cancer treatments, he continued, “they’ve told me that the likelihood of a typical man undergoing ADT having a major cardiac event is upwards of 30% to 40%.”

Impact on Everyday Care

Fatima Karzai, M.D., of the Genitourinary Malignancies Branch in NCI’s Center for Cancer Research, called relugolix “an exciting option” for men with advanced prostate cancer. Its most obvious role will be in men with advanced prostate cancer who also have cardiovascular disease, Dr. Karzai said.

Although trial participants who received relugolix had a more than 50% lower risk of serious cardiac events, she said it’s unclear exactly why it poses less of a threat to the heart. Some studies have suggested, she noted, that the difference in how the two drugs work may also influence how they affect plaque deposits in the cardiovascular system.

Relugolix is not the first GnRH antagonist to be approved by FDA to treat men with advanced prostate cancer. Degarelix (Firmagon) was approved more than a decade ago. However, degarelix is given as a monthly injection, and the injections can cause intense pain at the injection site, greatly limiting its use.

Dr. Karzai noted that there are still questions about using relugolix in patient care. For example, there might be problems with men’s ability to take a pill every day, as opposed to only having to get an injection of leuprolide or related drugs every few months.

Dr. Morgans agreed that this could be a concern but noted that men with more advanced forms of prostate cancer also receive other drugs that are taken as pills and have been generally good about using them as prescribed.

The ability to take a pill at home rather than having to travel to the doctor’s office for an injection definitely offers an upside, Dr. Morgans said. “It’s nice for patients to have that control.”