, by NCI Staff

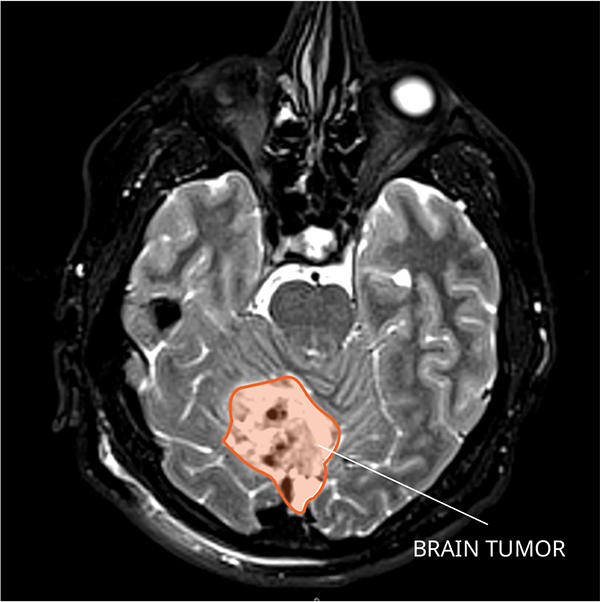

In up to one-third of children treated for a common and fast-growing type of brain tumor called medulloblastoma, the tumor will come back. But by the time doctors discover the cancer has returned—through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or a spinal tap—it is often at such an advanced stage that it is difficult to treat. Almost all children whose cancer returns after treatment ultimately die from the disease.

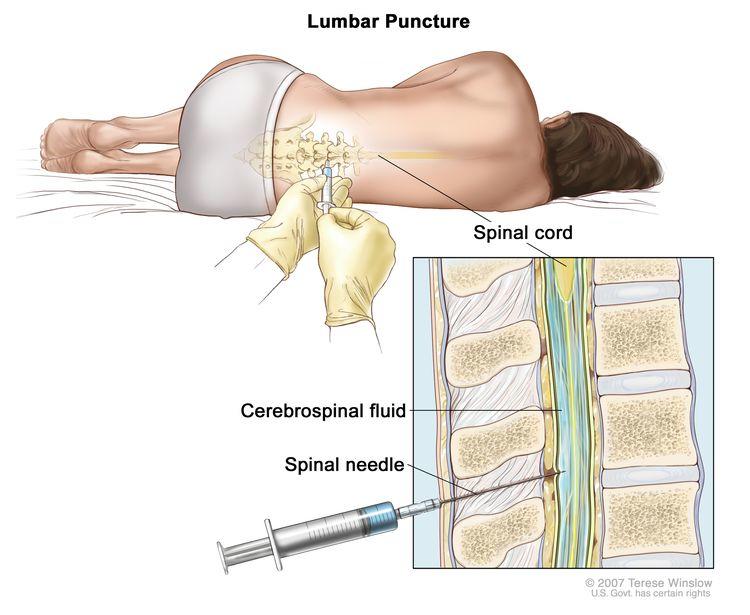

Now, researchers have developed a test that detects specific changes in DNA fragments, or cell-free DNA, shed from medulloblastoma tumor cells into the fluid surrounding the brain and spinal cord, known as the cerebrospinal fluid. Based on their findings from a recent study, the researchers believe this test could potentially be used to identify children who, shortly after completing treatment, still have evidence of cancer—known as residual disease—who are at high risk of relapse.

The findings appeared October 21 in Cancer Cell.

Being able to identify residual disease sooner than is possible with other methods could be very important for children with medulloblastoma, the researchers who led the study believe, giving doctors precious time to treat these patients with more aggressive therapy.

“Parents will tell you that once they reach the end of therapy, they get incredibly nervous because they’re just waiting and observing” to see if their child’s cancer comes back, said Giles W. Robinson, M.D., of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, one of the study’s leaders.

“If you have a test that can say you’re truly free of the disease at the end of treatment, that adds a huge amount of reassurance,” he said. But if the test shows you have evidence of residual disease, “then maybe that shouldn’t be the end of therapy.”

In the new study, researchers analyzed samples of cerebrospinal fluid collected at various points during and after treatment from children with medulloblastoma. Patients whose cancer came back, they found, were much more likely to have cell-free DNA with cancer-related characteristics in the fluid samples than those who remained cancer free.

“This study is groundbreaking,” said Marta Penas-Prado, M.D., of the Neuro-Oncology Branch in NCI’s Center for Cancer Research, who was not involved with the study. “It opens the door to a highly sensitive method of confirming the presence of tumor cells when imaging scans or conventional spinal taps aren’t conclusive.”

Dr. Robinson noted that more studies are needed to validate the test in additional groups of patients before we can determine how it might be used to direct treatment.

Improving Residual Disease Detection

Medulloblastoma typically forms in the cerebellum region of the brain and is very fast growing, with tumors spreading to other areas of brain and spinal cord through the cerebrospinal fluid. Depending on the age at diagnosis and whether the disease has spread, approximately 70% of kids with medulloblastoma will survive at least 5 years.

Doctors currently treat medulloblastomas with surgery, followed by radiation and chemotherapy. But in up to one-third of children with medulloblastoma, the cancer comes back after treatment.

MRI scans can help doctors see when a tumor has come back, but imaging cannot detect small amounts of remaining tumor cells—known as measurable residual disease, or minimal residual disease—that can indicate that treatment has not eliminated the cancer entirely. Also, imaging can be difficult to interpret, especially in patients who have undergone previous surgeries and radiation.

“There are things like scar tissue from surgery and from radiation that can look exactly the same as a tumor,” said Dr. Penas-Prado.

As a result, during the period of treatment after surgery, repeated spinal taps—in which a needle is inserted between vertebrae (under anesthesia) to collect samples of cerebrospinal fluid for analysis—are typically performed to look for any cancer cells that remain.

“The cerebrospinal fluid is currently used to identify metastatic tumor cells under the microscope,” said one of the study’s lead researchers, Paul Northcott, Ph.D., also of St. Jude. “But even in patients who have active disease, we often fail to detect tumor cells in the cerebrospinal fluid. It’s not a very sensitive test.”

Many studies have investigated whether identifying cancer-related changes in bits of genetic material in the blood or other body fluids can help to detect cancer recurrences sooner than other methods. The St. Jude team wanted to see if this approach could be used as a marker of measurable residual disease in cerebrospinal fluid from kids with medulloblastoma.

“What we have seen in diseases like leukemia is that, if you can detect signs of residual disease really early on, then you can make some treatment adjustments and actually improve the prognosis of those patients and potentially prevent relapse,” said Dr. Robinson.

“There’s a lot of interest in the concept of liquid biopsy for cancer, but the technology hadn’t been optimized for pediatric brain tumors,” said Dr. Northcott. “Through careful scientific trial and error and optimization at the lab bench, we found a protocol that can reliably identify the genomic variations characteristic of medulloblastoma.”

Genetic Analysis of Cerebrospinal Fluid Looks Promising

In the new study, the researchers analyzed available cerebrospinal fluid samples that had been collected from 123 children ages 6 to 11 years who were newly diagnosed with medulloblastoma and participating in a clinical trial. Using a technique called low-coverage whole-genome sequencing, they looked for cell-free DNA that had specific genomic changes, called copy number variations, that are characteristic of medulloblastoma.

In the samples collected from children after surgery but before the start of treatment, the new test detected these tumor-specific copy number variations—the marker for measurable residual disease—in 85% of children with disease that spread beyond the cerebellum (metastatic disease) and in 54% of children whose cancer had not spread. This suggested to the researchers that this test could identify disease when it was present in small quantities.

However, in samples collected after therapy had begun from 25 children within 3 months of their cancer returning, measurable residual disease was found in nearly all of them: 24 out of 25. In comparison, the test did not detect any measurable residual disease in 92% (193 out of 209) of cerebrospinal fluid samples from children whose cancer did not return.

What’s more, in 32 children whose MRIs showed no signs of cancer after radiation therapy but whose disease eventually returned, the test found measurable residual disease in half of these patients at least 3 months, and up to 2 years, earlier than imaging did.

“We could see that the disease was starting to re-emerge in that fluid well before we could see it on an MRI,” Dr. Robinson said. “This offers us an opportunity to intervene earlier than ever before.”

Spotting the return of disease this early also has scientific potential, Dr. Northcott said. With further improvements in technology and as researchers gain more experience in analyzing cell-free DNA, he continued, “we believe we will be able to make more molecular discoveries [that can explain] why the disease has not gone away.”

Still Work to Do before Test Can Be Used for Kids with Medulloblastoma

Dr. Robinson noted that it may take years before such a test is incorporated as part of standard care for children with medulloblastoma. Additional studies are needed to validate their results, he explained. However, it may not be long before this test is included in future medulloblastoma clinical trials “so we can better understand how to tailor therapy around detection of measurable residual disease,” he said.

Dr. Penas-Prado also cautioned that this test has only been studied in children and may not apply to adults with medulloblastoma. This brain cancer is now commonly grouped into four subtypes, based on the cancer’s genetic makeup. The majority of adults have a subtype of medulloblastoma called Sonic Hedgehog. This subtype is less common among children.

“It turns out in this study that the tumors with the Sonic Hedgehog molecular subtype were less likely to shed DNA into the cerebrospinal fluid,” she said. “That means this [test] may be less applicable for adults with medulloblastoma than for children.”

In an accompanying editorial, John R. Prensner, M.D., Ph.D., and Scott L. Pomeroy, M.D., Ph.D., of the Broad Institute of Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University noted that analyzing cerebrospinal fluid may be less practical for patients not being treated as part of a clinical trial where cerebrospinal fluid is collected at different time points.

Although further research is needed, they continued, “the lessons gained from this work will inevitably catalyze important conversations regarding the development and standardization of measurable residual disease assays for patients with medulloblastoma.”