February 21, 2019, by Norman E. Sharpless, M.D.

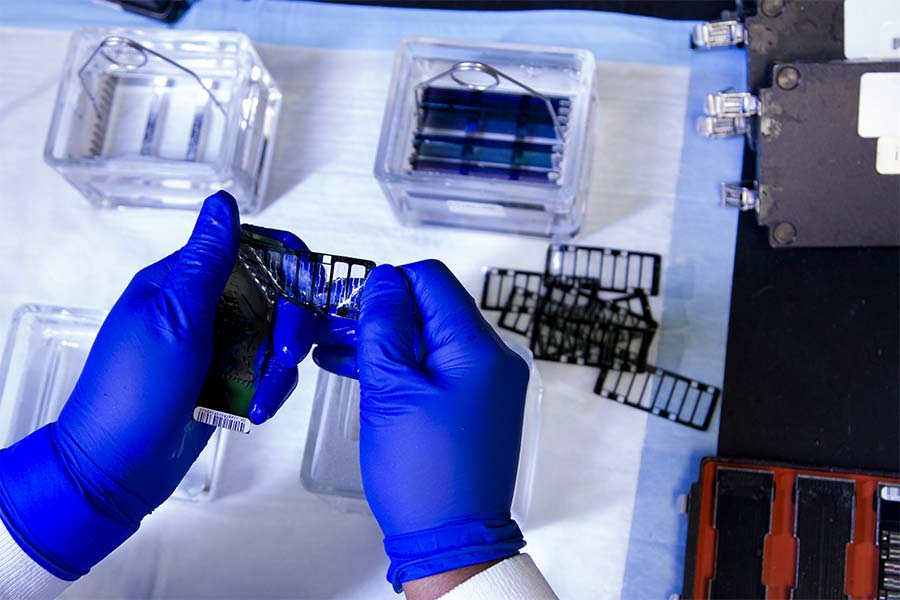

NCI’s SBIR/STTR helps small businesses advance the development of new technologies for research and cancer treatments.

Credit: National Cancer Institute

NCI is the federal government’s principal agency for cancer research. To advance that mission, NCI leads many highly visible activities related to basic research, clinical trials, training, and coordination of a national cancer plan.

Perhaps less well-known are robust NCI programs specifically set up to help small businesses develop and commercialize innovative devices, diagnostics, algorithms, and therapeutics to improve cancer research, prevention, detection, and care. Early in my career as an independent scientist, I remember being surprised not only by the existence of these programs, but also by their scale. I then very quickly came to learn, through personal experience, of their importance.

NCI’s Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs have been in existence for several decades. The programs provide seed funds to encourage small, innovative companies to participate in research and development activities that have the potential for private-sector commercialization and public benefit.

Last week marked two important moments for NCI’s SBIR/STTR programs. One was the presentation of a report from a working group, convened under the National Cancer Advisory Board (NCAB), with recommendations on how to improve and strengthen the programs. And the second was the release of a study, commissioned by NCI, to help evaluate the economic impact of these programs.

The report and study provide insight into a strong set of NCI programs that many in the cancer community may not be familiar with.

My Personal Experience with SBIR

All federal agencies that provide at least $100 million in funding for research and development are required by law to set aside a portion of their extramural research budget for SBIR and STTR programs. In fiscal year (FY) 2019, the SBIR/STTR set-aside is 3.65% of NCI’s extramural budget, that is, approximately $160 million for commercialization activities. This policy makes these programs one of the largest sources of financing for early-stage cancer biotechnology in the United States.

Before becoming NCI director, I was able to experience firsthand just how invaluable these startup funds can be for getting novel ideas off the ground.

When I was at the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, we were studying compounds that inhibit enzymes involved in cell division. Not only did these compounds cause healthy bone marrow cells to stop dividing temporarily, which we called “pharmacological quiescence,” but they also made them resistant to DNA-damaging agents like radiation and chemotherapy.

Although radiation and chemotherapy are important cornerstones of cancer therapy, as anybody who has ever received them can tell you, they can do more than just kill tumor cells. Both also damage healthy cells, particularly dividing cells in the bone marrow. This bone marrow damage leads to many of the most common and most important toxicities of cytotoxic chemotherapy: anemia, susceptibility to infection, and increased bleeding risk.

The results of our work suggested that the compounds we were studying might prevent or limit the damage to bone marrow caused by standard cancer therapies, like radiation and cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Hoping to advance this approach toward clinical trials and ultimately develop a nontoxic drug that could prevent the damaging side effects of radiation, I applied for a basic research R01 grant from the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). While waiting for NIAID to decide whether to fund the proposal, I was told by a NIAID program officer that, while they liked my proposal, they thought it represented a commercial opportunity and therefore was better suited for an SBIR award.

This was the first I had heard of these commercialization awards and I recall my exact words during that phone call: “What’s an SBIR?”

After learning more about these programs, it became clear this would be a good approach to develop our ideas. In 2008, I joined with several colleagues to launch a startup company that applied for NIAID SBIR funds. We received our first SBIR award in 2009 and, over the next few years, received approximately $5 million in additional SBIR funds from NIAID, NCI, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases to advance our research.

This early SBIR funding allowed our early-stage research to grow rapidly and achieve important scientific milestones, enabling it to subsequently garner venture capital backing from the private sector. Although the amount of funds eventually raised privately for this effort was many times larger than the SBIR support, it is important to note that the early support from the SBIR program made the later success possible.

Fast forward to the present and the company is now a publicly traded company, has conducted successful phase II clinical trials in small cell lung cancer and triple-negative breast cancer, and is currently testing three clinical-stage compounds for use in cancer patients.

It is still unclear whether this line of studies will lead to a new FDA-approved therapy for patients with cancer or other indications (the vast majority of efforts to develop oncologic therapeutics from scratch ultimately fail), but the results thus far have exceeded my own expectations.

How SBIR/STTR Programs Are Helping the Broader Community

Based on these experiences, I have been enthusiastic about the NIH SBIR/STTR programs for many years and consider them to be true “engines of innovation” for biotech companies.

Once I became NCI director (which required divesting from all industry relationships to enter federal service), I came to learn about the exciting technologies and therapies NCI’s SBIR/STTR programs are supporting.

These programs are an integral component of our mission to bring cancer medicine and technology to patients as quickly and effectively as possible. And, having had a positive personal experience with NIH SBIR/STTR programs, I wanted to better understand how NCI’s SBIR/STTR programs were helping the broader community and whether we might be able to strengthen the programs.

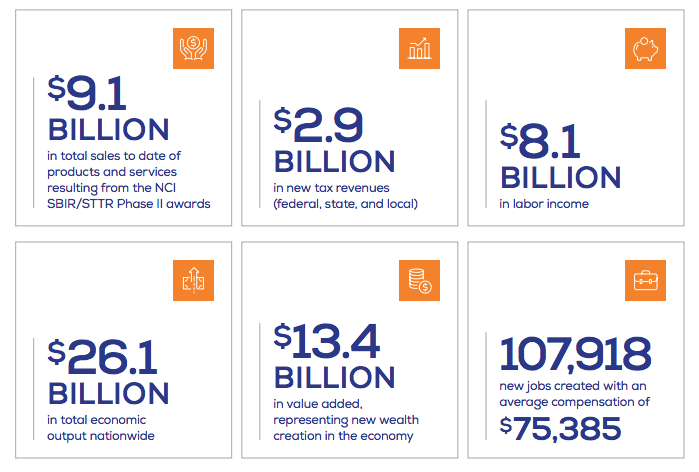

Toward that end, we took on an assessment of the NCI SBIR/STTR programs’ overall contribution to cancer research and the national economy. NCI commissioned an economic impact study last year that looked at how NCI SBIR/STTR investments from 1998–2010 translated into economic and scientific impact today. Although I encourage you to read the full report, here are some of the study’s highlights:

- Between 1998 and 2010, NCI’s investment of $787 million in SBIR/STTR funds in 444 companies led to 247 technologies and agents that are commercially available today, including 71 FDA-approved products.

- NCI’s SBIR/STTR programs led to an estimated $26.1 billion in total economic output nationwide, including product sales, tax revenue, and job creation. That’s a 33:1 return on investment.

- During the period 1998 through 2010, more than 400 (65%) of the surveyed technologies supported by the SBIR/STTR programs were developing a treatment option for a subgroup of patients who previously lacked options.

One example of a product developed with support from NCI’s SBIR/STTR program is the Infinium assay for genotyping, which is being used in the NIH All of Us Research Program, in other basic and clinical research, as well as by commercial companies like 23andMe and Ancestry.com. The NCI SBIR/STTR grantee, Illumina, developed the base technology for this assay.

The array of technologies and therapies, from advanced imaging approaches to cutting-edge immunotherapies, that SBIR/STTR programs support is impressive. And the economic impact study’s findings reveal the compelling story behind these efforts, one that supports continued investment in small businesses’ early-stage development of new cancer-related technologies and therapies.

Working Group Recommendations

In the spirit of continuous improvement, I asked the NCAB to convene a working group of NCAB members, along with individuals with expertise in small business, technology development, and translational research, to advise NCI on several strategic questions related to the SBIR/STTR programs. Examining such questions in a focused way would yield a fresh perspective and constructive suggestions on how to make a good program even better.

NCI Director Dr. Norman E. Sharpless

Credit: National Institutes of Health

Last week, at a regularly scheduled NCAB meeting, the working group presented its findings. Their recommendations to strengthen the SBIR/STTR programs included increasing award size, broadening diversity of participants and peer reviewers, enhancing assistance to grantees, improving metrics for continuous evaluation, and expanding awareness of the programs. NCI leadership embraces the working group’s report and will work toward implementing its recommendations.

We encourage small biotech businesses to learn more about the SBIR/STTR programs at NCI and join the many companies that have already experienced the benefits of SBIR/STTR funding to advance their early-in-development innovative ideas.

We believe these efforts to commercialize cutting-edge cancer science are economically significant, but most importantly, these programs demonstrably provide a means of getting novel technologies from the bench into broad clinical use in a way that will directly help patients with cancer.