May 10, 2018, by NCI Staff

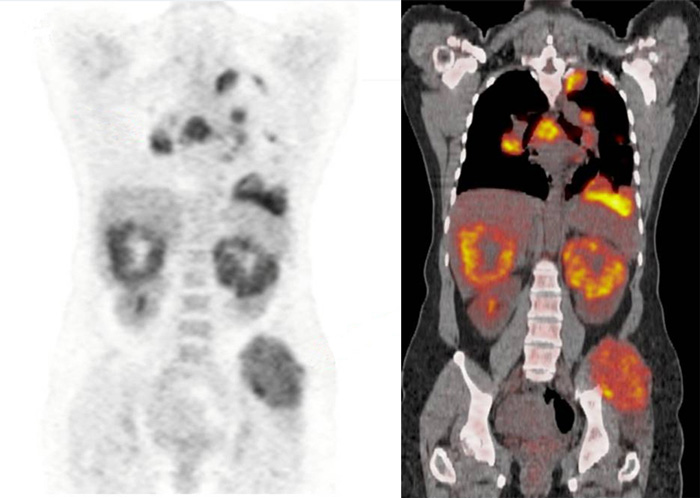

FDG PET/CT scans from a patient with metastatic renal cell carcinoma.

Credit: PLOS One 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153321. CC BY 4.0.

On April 16, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the immunotherapy drugs nivolumab (Opdivo) and ipilimumab (Yervoy) in combination as an initial, or first-line, treatment for patients with advanced kidney cancer whose disease has an intermediate or poor prognosis.

This is the first immunotherapy regimen to be approved by FDA for the initial treatment of patients with kidney cancer. Nivolumab was previously approved to treat patients with advanced kidney cancer whose disease had gotten worse after treatment with standard first-line therapy.

The new approval was based on results from an international phase 3 clinical trial. In the trial, people with intermediate- or poor-risk advanced kidney cancer who received the immunotherapy combination lived longer overall and were more likely to have their tumors shrink compared with those treated with sunitinib (Sutent). Results from the trial, which was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Ono Pharmaceutical, were reported April 5 in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).

Better Outcomes with Immunotherapy

The trial, called CheckMate 214, involved nearly 1,100 patients with previously untreated advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC), which is the most common type of kidney cancer. (For this study, advanced RCC was defined as cancer that was not amenable to potentially curative surgery or radiation therapy or that had metastasized to other areas of the body.)

Participants were randomly assigned to receive either nivolumab plus ipilimumab, both of which are immune checkpoint inhibitors, followed by nivolumab alone as a maintenance therapy, or sunitinib, an angiogenesis inhibitor that is a standard treatment for patients with advanced kidney cancer.

The majority of patients in each treatment group had intermediate- or poor-risk disease. Oncologists use well-established risk factors to categorize patients with advanced kidney cancer into favorable-, intermediate-, and poor-risk groups. Approximately 75% of all patients with advanced kidney cancer have intermediate- or poor-risk disease.

At 18 months after initiating treatment, 75% of patients treated with the immunotherapy combination were still alive, compared with 60% of those treated with sunitinib. At a median follow-up of 25 months, the median overall survival for patients treated with the immunotherapy combination had not been reached. For patients treated with sunitinib, it was 26 months.

More patients assigned to the immunotherapy combination than to sunitinib experienced an objective tumor response (42% versus 27%), including complete responses (9% versus 1%), meaning their cancer was no longer detectable.

Fewer patients in the trial treated with nivolumab and ipilimumab than with sunitinib experienced serious side effects (46% versus 63%). However, more patients in the immunotherapy group discontinued treatment because of side effects (22% versus 12%). There were eight deaths likely related to treatment among patients treated with nivolumab and ipilimumab, the trial researchers reported, and four among patients treated with sunitinib.

Despite the prevalence of side effects and greater percentage of patients stopping treatment, patients who received the immunotherapy combination reported higher quality of life throughout the study.

Patients with Favorable-Risk Disease Fared Better with Sunitinib

The improvements in survival and tumor response rates seen in patients with intermediate- and poor-risk disease treated with the immunotherapy combination were not seen in patients with favorable-risk disease.

In fact, among patients with favorable-risk RCC, those treated with sunitinib had a higher tumor response rate than those treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab (52% versus 29%) and longer progression-free survival (25.1 months versus 15.3 months), noted Brendan D. Curti, M.D., of the Providence Cancer Institute, Portland, OR, in an accompanying editorial in NEJM.

The study authors acknowledged the different outcomes for patients with favorable-risk disease, but said that the results should be “interpreted with caution because of the exploratory nature of the analysis, the small subgroup sample, and the immaturity of survival data.” However, they continued, the disparate results “highlight the need to better understand the underlying biologic processes driving responses to these two different treatment regimens.”

Eric Jonasch, M.D., a genitourinary oncologist at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, added that the findings in favorable-risk patients suggest that their tumors may have a different biology that might be defined by a lack of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment.

“I think we need to perform further studies to really understand from a [tumor microenvironment] perspective what the differences are between favorable-, intermediate-, and poor-risk patients,” said Dr. Jonasch, who was not involved in the study.

Moving Beyond Blocking the Tumor Blood Supply

Since 2005, FDA has approved numerous drugs like sunitinib that target angiogenesis, the growth of new blood vessels that nourish tumors, to treat kidney cancer. Unlike antiangiogenesis drugs, nivolumab and ipilimumab work by blocking proteins that deter or dampen an immune response against tumors.

The new approval will likely change how patients are treated, said Dr. Jonasch. Now, patients with intermediate- or poor-risk disease likely will receive nivolumab and ipilimumab as their initial treatment, he suggested.

“I think the key [research] question now is what is the right strategy in terms of combining checkpoint inhibitors with other checkpoint inhibitors or with targeted drugs like lenvatinib or cabozantinib, and what are those strategies giving us in terms of complete responses and durable responses,” Dr. Jonasch said.

The underlying biological mechanisms of why tumors respond and develop resistance to these treatment strategies need to be studied so clinicians can better identify individuals who may be most likely to benefit from a particular strategy, he explained.

Both Dr. Jonasch and Dr. Curti suggest that the complete response rate seen with the immunotherapy combination moves the bar for treating patients with advanced RCC.

“The 9% complete response rate will probably be the new standard that we will strive to surpass as we try to improve on these results,” said Dr. Jonasch.