Widely-used anti-inflammatory drugs make tumours in mice more responsive to treatments that harness the power of the body’s own immune system to tackle cancer, according to research funded by Cancer Research UK and published in the journal Cancer Discovery.

Scientists based at the Cancer Research UK Manchester Institute, part of the University of Manchester, found that a type of immunotherapy worked better and faster in mice when combined with anti-inflammatory drugs.

“These proof-of-concept results are exciting,” said lead researcher Dr Santiago Zelenay. “Our work supports evidence that widely used anti-inflammatory drugs, commonly used to treat conditions like arthritis, can favour a type of inflammatory response that boosts the cancer-restraining function of our immune system.”

Cutting off cancer’s escape route

The scientist looked at a type of immunotherapy called checkpoint inhibitors. These immune-boosting treatments became a breakthrough cancer treatment in the last decade, approved to treat some lung cancers, melanomas and head and neck cancers, among others. But despite their promise, not everyone responds to checkpoint inhibitors, something scientists are keen to change.

When the researchers treated tumours growing in mice using a checkpoint inhibitor, less than 30% of the mice responded to treatment.

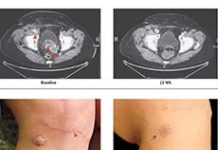

But when the mice were given the checkpoint inhibitors along with a common anti-inflammatory called celecoxib (Celebrex), up to 70% of the mice responded to the combined treatment with many having their tumours fully eradicated. Celecoxib targets a protein called COX-2, which helps cancer cells escape the immune system and grow aggressively. By cutting off the cancer’s escape route, the drug can help make checkpoint inhibitors more effective.

Similar results were also achieved when combining checkpoint inhibitors with steroid anti-inflammatory drugs – a surprising finding, as steroids are widely considered to suppress the immune system.

Zelenay said: “Improving the efficacy of the immune checkpoint blockade remains a major clinical need, so our progress in this area is very exciting.

“Our study has identified mechanisms by which anti-inflammatory drugs can rapidly enhance an immune response in tumours that can prevent their growth.”

Giving immunotherapy a boost

“Checkpoint inhibitors are widely used in the treatment of melanoma and lung cancer to name a few, but they don’t work for everyone. Making them more effective would make a huge difference to many, so finding ways to unleash their potential is vital,” said Michelle Mitchell, chief executive of Cancer Research UK.

“Although this is early research, funding in this area is important because it can set the course for practice-changing clinical trials later down the line. Repurposing drugs that have already passed safety tests is a great opportunity to save more lives with tools already at our disposal.”

The results of this research were supported by analysing fragments from surgically-removed patient’s tumours, where treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs produced similar molecular changes as those seen in mice. This gives hope that the combination could be effective in patients.

Researchers will test combinations of celecoxib with checkpoint inhibitors in types of lung, kidney and breast cancers in the LION trial, set to launch towards the end of 2021 at the Christie NHS Foundation Trust. Funded by The JP Moulton Charitable Foundation and The Christie Charity, the study hopes to determine if, and in which cases, these combinations might work best in patients.

These trials are necessary to see if combining anti-inflammatories with immunotherapy treatments are safe and effective for humans, and Zelenay stresses that this research is not suggesting patients should self-medicate with any of these drugs.