If I asked you what causes lung cancer, you’d probably say smoking.

And you’d be right, smoking tobacco is the biggest cause of lung cancer in the UK. Even light or occasional smoking increases the risk of lung cancer, and that includes breathing in other people’s cigarette smoke.

But some people who get lung cancer don’t smoke. In fact, up to 14% of people with lung cancer in the UK have never smoked.i

To put this into perspective, if lung cancer in people who have never smoked was a separate disease, it would be the eighth most prevalent cause of cancer-related death; higher than ovarian cancer, leukaemia and lymphoma.i

In some ways, lung cancer is a distinct disease in people who have never smoked, as it has unique molecular and biological characteristics, and it responds differently to treatment.

But regardless of your smoking status, your route to diagnosis as someone with lung cancer symptoms should be the same, right? You notice your symptoms; you go to the doctor; you get a diagnosis.

Unfortunately, as new research, funded by us and published today Psycho-Oncology, has revealed, that isn’t always true.

What we already knew

Before we dive into that, we’ll have to do a little bit of scene setting. And to do that, let’s go back to last year.

A group of researchers at University College London (UCL) were faced with a problem.

There was evidence that people who have never smoked were facing delays in being diagnosed with lung cancer, but it wasn’t clear how their experiences differed from those of smokers.

As a starting point, they set out to review the research that was already out there to date.

Over the course of a year, they analysed seven quantitative and three qualitative studies about people’s experiences in relation to symptom awareness, help‐seeking, and the lung cancer diagnostic pathway, comparing people with and without a history of smoking.

This wasn’t just an exercise in finding out what we know. Crucially, this review highlighted what we didn’t know to lay the groundwork for more research into lung cancer in people who have never smoked.

And one of their main findings was that there was a lack of evidence about why there were delays in diagnosis for people who have never smoked. The research indicated that people who have never smoked had a different experience to current and former smokers in getting a diagnosis, but the reasons why were still unclear.

That brings us to where Dr Georgia Black and her team at UCL, Queen Mary’s and the University of Surrey took the lead, and to the research published today.

Why the delay in diagnosis?

The team, who were part of the group that performed the review, followed up on this review with another study, this time interviewing people with lung cancer to figure out similarities and differences in help-seeking behaviour depending on smoking status.

This is the first time people who have never smoked have been compared directly with current and former smokers with regards to help seeking and experiences in primary care, primary care being, for the most part, their GP.

The study interviewed 40 people with lung cancer: 20 of those were people who had never smoked, 11 were former smokers and 9 were current smokers.

And what they found paints quite a complex picture.

“The thing that’s interesting is that there are lots of similarities between smokers and non-smokers,” says Black.

“Almost no one thinks they have lung cancer when they have a cough or shortness of breath, or other similar symptoms. Even if you’re a smoker, that’s not the first thing you think of.”

“People who have never smoked rarely had ‘dramatic’ or disruptive symptoms, and regularly attributed them to common illnesses like colds or hay fever, which meant they didn’t initially think that making an appointment with their GP was necessary.”

Smokers on the other hand were more likely to have multiple symptoms, other chronic health conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and to have disruptive symptoms, like coughing up blood.

That meant that while they might notice new symptoms as unusual, and would make an appointment to see a doctor, they often put it down to existing health conditions rather than suspecting cancer.

“When people who smoke experience a cough or breathlessness, their automatic thought is, ‘oh, my COPD is playing up’ or ‘my asthma is playing up,’” Black explains.

“And so, because they tend to have COPD or asthma check-ups regularly, it doesn’t feel like a massive leap for them to go and get it checked out.

“Whereas non-smokers, who don’t have a chronic disease and have much less dramatic symptoms assume it will go away. It takes a long time for them to realise something is wrong.”

But it was once they got past the point of their initial appointment that the biggest differences began to appear.

The study revealed that smokers tended to remain vigilant until they received a diagnosis and were quick to arrange follow-up appointments if medication they were originally prescribed, like antibiotics, didn’t clear their symptoms.

By contrast, people who have never smoked were falsely reassured by their GP that their symptoms were benign, as it aligned with the patient’s own thoughts.

“After that first appointment, if it’s something you’re not at all worried about, and you’re not monitoring it, you’re going to wait until something dramatic happens until you do anything again.”

This often resulted in long periods before they thought about booking another appointment, even in some cases in the presence of alarm symptoms like coughing up blood.

“Whereas we found that smokers, whose antibiotics or new inhaler didn’t work, would be back in the surgery as soon as they could.”

So, whilst smokers and non-smokers may both put off contacting primary care initially, the real delays for people who have never smoked begin after that, with some waiting up to several months before going back to the GP.

But with any primary care interaction, the patient’s viewpoint is only one half of the story.

The other half is that of the healthcare professionals (HCPs), the ones able to make the decisions about further tests. Black is also considering how their behaviour and decision making might be affected by a patient’s smoking status.

In her current research, she’s conducting in-depth interviews with HCPs in other to research their behaviours and advance our understanding of this complex topic even further.

The view from the other side

But while we might have to wait a little longer for insights into the behaviours of HCPs, we do already know that it isn’t just patient factors that might delay their lung cancer diagnosis.

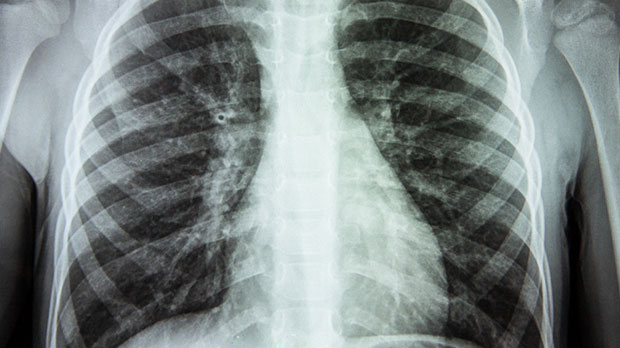

Dr Stephen Bradley, a practicing GP and clinical research fellow at the University of Leeds, is researching how we can improve lung cancer diagnosis in primary care. Specifically, his research focusses on the accuracy of chest x-ray, one of the main tests used to diagnose lung cancer.

Bradley’s research has shown that chest x-rays are an effective tool for ruling out lung cancer in low-risk patients, including people who have never smoked. However, his research has also shown that chest x-ray referrals don’t occur at the same rate in all GP surgeries.

“We found that there was a big variation in how often GP practices were using chest x-rays,” says Bradley.

“And we also found that this variation is not accounted for by differences in the population, or by the numbers of smokers, or entirely by age, and so on.”

And if the variation can’t be explained by chance, it means it’s likely to be down to the culture of individual GPs and practices and how willing they are to refer their patients for x-rays.

“Historically, GPs have been a bit reticent to use investigations too frequently,” Bradley continues. “For example, they may worry sometimes about putting too much burden on the health service.

“But we know that the practices that refer more patients under urgent suspected cancer pathways see better patient outcomes. So, we wonder whether the same holds for chest x-ray. That’s work that I’m doing now.

“I think there’s an opportunity here for us to have a more permissive attitude to using chest x-ray for patients who we previously might have considered low risk or so low risk that they don’t warrant any investigation at all,” adds Bradley.

“My intuition is that a lot of these patients who don’t smoke aren’t getting the chest x-ray in the first place, so they’re not getting an investigation promptly enough, and that delays diagnosis.”

And concurrently, if we can encourage urgency in people who have never smoked so they’re aware of potential lung cancer symptoms and increase vigilance of symptoms after initial contact with primary care, we may be able to decrease diagnostic delays.

“Rather than over-reassuring a patient,” says Black. “GPs can help by encouraging patients to monitor their symptoms and tell them to come back if their symptoms don’t go away.

“GPs can do quite a lot in the way they communicate to increase the patient’s vigilance. There’s a balance to be struck between being informative and encouraging without causing unnecessary anxiety.”

Angela’s Story

Angela, who lives in Windsor, was diagnosed with lung cancer when she was 39. The mother of two had a bit of a cough over the winter and went to see her GP. After two rounds of antibiotics and a week of steroids, her cough still wouldn’t clear and she was sent for an x-ray, which showed some shadowing on her lungs.

100vw, 200px”></p>

<p class=) Angela running her third London Marathon in April 2017

Angela running her third London Marathon in April 2017

“I was a non-smoker and also in the middle of a project to run a half marathon every month for a year, so it wasn’t expected to be anything serious,” Angela said. “My doctor and I never discussed lung cancer specifically. It was more along the lines that it was unlikely to be anything sinister as I was generally fit and active.”

But a follow-up ultrasound revealed fluid around her heart, and she was rushed to hospital. Once the fluid was drained, doctors began investigating the cause. They took a CT scan, a PET scan and a biopsy from one of the shadows.

Angela was diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer, which had spread to both lungs, as well as her liver, adrenals and lymph nodes. As a keen runner and non-smoker, the diagnosis came as a huge shock.

“Just six weeks before I’d run a half marathon,” she said.

After eight years of treatment, Angela still has one visible tumour on her right lung. Now 48, she is still very active and continues to run – though sometimes a bit slower than she would like. She is planning to run the London Marathon again next year.

“I still have rubbish days when I want to curl up on the sofa and say, ‘why me?’ But most of the time it’s about getting on with life, doing what I want to do while I can.

“I’m a Trustee of the ALK Positive UK charity and we support patients diagnosed with ALK+ lung cancer.”

Building our understanding

Lung cancer in people who have never smoked, despite its relative scarcity compared to lung cancer in smokers, is a growing field of interest in research in a variety of fields.

In September of this year, Professor Charles Swanton, Cancer Research UK’s chief clinician, presented results from TRACERx that uncovered how air pollution can cause lung cancer in people who have never smoked.

And TRACERx EVO, a new programme to build on the discoveries made in TRACERx, will continue to investigate further causes of lung cancer in people who have never smoked.

Using the findings from research like Black’s and Bradley’s, alongside those from TRACERx, we can build a more complete picture of lung cancer in people who have never smoked.

An increased understanding of the biology of the disease can lead us to newer, more effective treatments, and unpicking the behaviours of both patients and HCPs can help us to devise ways of minimizing unnecessary delays in diagnosis.

“It feels as if we are capturing the Zeitgeist with this topic,” Black adds. “And that’s thrilling as a researcher, to know we’re not alone in worrying about this problem.

“There’s a real movement towards trying to collectively solve this problem at all levels, in radiology, at a molecular level and at a behavioural science level. And that’s how you get things solved.”

Diagnosing lung cancer early, in both smokers and people who have never smoked, can make all the difference to survival outcomes.

When diagnosed at its earliest stage, 57% people with lung cancer will survive their disease for five years or more, compared with just 3% of people when the disease is diagnosed at the latest stage.

If we can diagnose more lung cancers earlier, we can see more people with lung cancer surviving their cancer for longer.

And research like this is showing us just how we can make that happen.

References

i. Bhopal A, Peake MD, Gilligan D, Cosford P. Lung cancer in never-smokers: a hidden disease. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2019;112(7):269-271. doi:10.1177/0141076819843654