, by NCI Staff

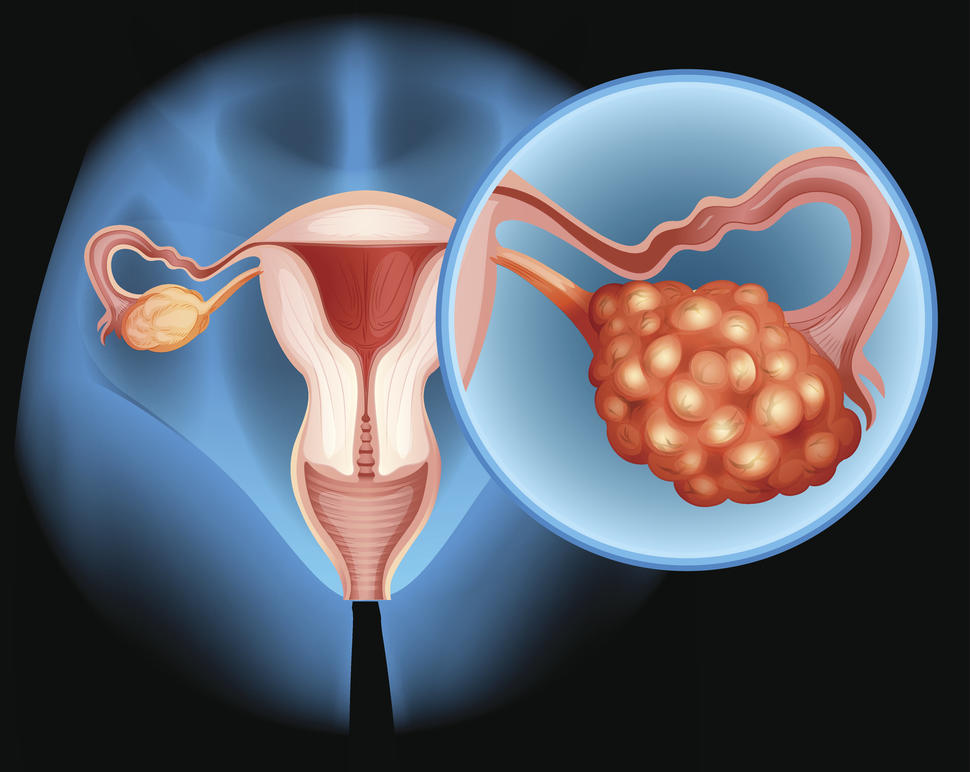

New results from a large clinical trial provide the first strong evidence that a rare form of ovarian cancer, known as low-grade serous ovarian cancer, should be treated differently from other forms of the disease.

The trial involved women with low-grade serous ovarian cancer that had come back after earlier treatments. Participants who received the targeted drug trametinib (Mekinist) lived longer without their cancer progressing than those who received standard treatment. Trametinib, which is taken as a daily pill, blocks the activity of a protein called MEK that fuels tumor growth.

“Previously, patients with any type of ovarian cancer were treated with the same chemotherapy when their cancer relapsed,” or came back, explained Christina Annunziata, M.D., Ph.D., of NCI’s Women’s Malignancies Branch, who was not involved in the trial. “Now, people with low-grade serous ovarian cancer have a new, more effective treatment option.”

Indeed, “[t]his is the first randomized clinical trial to show a benefit of any therapy specifically for women with this rare and understudied form of ovarian cancer,” said study leader David Gershenson, M.D., professor of gynecologic oncology and reproductive medicine at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

The findings, published February 5 in The Lancet, “are very significant, given that there are few effective treatment options for patients with low-grade serous ovarian cancer that has recurred,” said Ursula Matulonis, M.D., chief of gynecologic oncology at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, who also was not involved with the trial.

However, the possible side effects of trametinib, which can be severe, may factor into how and when this drug is used, experts said.

How low-grade serous ovarian cancer differs from most common form

Low-grade serous ovarian cancer, which accounts for about 5% of all cases of ovarian cancer, has been recognized as a distinct form of ovarian cancer only since 2004.

Compared with the most common form of ovarian cancer, known as high-grade serous ovarian cancer, the low-grade form grows more slowly and is more likely to be diagnosed in younger people. Although it is less likely to respond to chemotherapy than high-grade disease, people with the low-grade form tend to live longer after their diagnosis.

Like other forms of ovarian cancer, low-grade serous ovarian cancer is often diagnosed when the cancer is at an advanced stage. And the cancer will eventually come back, or recur, in at least 70% of people with advanced disease, Dr. Gershenson said.

If the cancer does recur, he said, treatment options include several types of chemotherapy; hormone therapies, which are also used to treat certain types of breast cancer; and bevacizumab (Avastin).

People may live for a relatively long time after the cancer recurs, requiring treatment for most of that time. One treatment may work for a while, and then when the cancer progresses, a person is switched to a new treatment, Dr. Gershenson continued.

Targeting underlying tumor biology with trametinib

As researchers have learned more about the underlying biology and genetic hallmarks of different cancers, including ovarian cancer, they have begun developing more-targeted therapies designed to block specific proteins that may drive cancer growth.

In the case of low-grade serous ovarian cancer, roughly half of all patients have tumors with genetic alterations that rev up the activity of the MEK protein, fueling tumor growth and spread. So, when drugs such as trametinib that could block MEK activity were developed, it made sense to test them in people with low-grade serous disease, Dr. Gershenson explained.

Trametinib is already approved for treating certain forms of melanoma, thyroid cancer, and non-small cell lung cancer.

In 2013, Dr. Gershenson and others reported results from a small study showing that a different MEK-targeting drug could shrink tumors in people with low-grade serous ovarian cancer. These findings set the stage for larger, more rigorous studies of MEK-targeted drugs as treatments for people with this cancer.

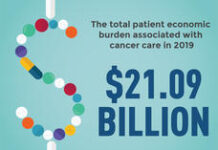

The clinical trial of trametinib, known as GOG 281/LOGS, was funded in part by NCI and conducted in the United States and United Kingdom. It enrolled 260 people with recurrent low-grade serous ovarian cancer.

Half of the trial participants were randomly assigned to receive daily trametinib and half to receive one of five commonly used, “standard-of-care” treatment options. These included the chemotherapy drugs paclitaxel, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, and topotecan, which are given intravenously, and the hormone therapies letrozole and tamoxifen, which are given as pills. Nearly half of all study participants had received three or more prior therapies for their cancer.

People in the trametinib group survived for a median of 13 months without dying or having their cancer progress, compared with just over 7 months in the standard-of-care group. In addition, tumors in 26% of people in the trametinib group shrank in response to treatment, compared with only 6% of those in the standard-of-care group.

Side effects of trametinib a concern

People in the trametinib group experienced more serious side effects than people in the standard-of-care group. The most common serious side effects seen with trametinib included skin rash, low red blood cell counts (anemia), high blood pressure, and diarrhea.

These side effects “are treatable but could also require some patients to reduce the dose or stop taking the drug,” Dr. Annunziata said.

“There are a wide range of side effects that can be seen, so oncologists need to be aware of these” and closely monitor their patients who are on the drug, Dr. Matulonis cautioned.

Participants in the trial also answered standard questionnaires to assess their quality of life at several points during treatment. Although people taking trametinib reported a worse quality of life at 3 months after starting treatment, there was no difference in quality of life between the groups in assessments at later timepoints, Dr. Gershenson said.

Trametinib “should be seriously considered” when a patient’s cancer first comes back, he continued. However, because of the drug’s potential side effects, it may not always be the go-to treatment. “For instance,” he explained, for some patients “it may be better to start with something like [the hormone therapy] letrozole, because the side effects are much better tolerated.”

Ultimately, Dr. Gershenson said, patients and their physicians will need to weigh the potential harms and benefits of trametinib against those of other treatment options.

Although experts agree that trametinib should be considered a new standard of care for patients with recurrent low-grade serous ovarian cancer, Novartis, the company that makes the drug and contributed study funding, said it currently has no plans to seek Food and Drug Administration approval for this particular use.

However, after the study results were presented at a 2019 conference, trametinib was put on the National Comprehensive Cancer Network compendium of drugs for low-grade serous ovarian cancer. And that has allowed most people who might benefit from the drug to get insurance coverage, at least in the United States, Dr. Gershenson said.

Some important questions still need to be answered about how best to use trametinib, Dr. Annunziata said. They include whether trametinib should be given only after someone has received chemotherapy or hormone therapy or as their initial treatment, as well as whether the drug should be given alone or with other treatments.

“Our study will undoubtedly lead to other trials testing combinations of a MEK inhibitor and other drugs,” including hormone therapy, Dr. Gershenson said. “We need to accelerate our efforts toward the discovery of additional novel drugs or regimens,” including options with fewer serious side effects.

He and his colleagues are also doing additional experiments to identify biomarkers that can best predict which patients with low-grade serous ovarian cancer are most likely to benefit from drugs that target MEK.