Tingting Zhang, PhD, is a thyroid cancer survivor and a patient advocate member of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO). Dr. Zhang is the chief executive officer of ONEiHEALTH, a virtual remote care navigation platform. She received her PhD in cancer biology from Columbia University and won a Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Information Processing Techniques Office special commendation in 2005 for her anti-bioterror work at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Dr. Zhang’s work on digital-enabled care management in Asia won a 2019 ASCO Breakthrough award. You can follow Dr. Zhang on X, formerly known as Twitter. View Dr. Zhang’s disclosures.

From 2000 to 2021, the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) population in the United States doubled to 24 million people, which is close to 7% of the total U.S. population, based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau. This population includes 5.2 million Chinese people, 4.8 million Indian people, 4.4 million Filipino people, 2.3 million Vietnamese people, 2 million Korean people, 1.6 million Japanese people, and people from a dozen or so other Asian countries or regions. By 2040, the AAPI U.S. population is expected to rise to 35 million people.

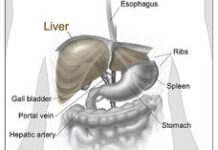

For people in AAPI communities, it is important to know how their cancer risk can differ from the general U.S. population. Among AAPI people with cancer, lung cancer causes the highest number of deaths every year. Yet overall, 3 out of 5 Asian women, and 4 out 5 Chinese women, with lung cancer do not smoke. Asian Americans also have higher incidences of liver cancer and stomach cancer that are often related to the hepatitis B virus and H. pylori bacteria, respectively, according to a 2022 report published by the American Association for Cancer Research. Meanwhile, cancers of the nose and throat in middle-aged Asian Americans are often related to the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), whereas in White people, these types of cancer are more commonly related to the human papillomavirus (HPV). Even though EBV infects a majority of the world’s population, there is an 18-times higher incidence rate of nose and throat cancers in southern Guangdong in China and in people who trace their ancestry to this region. The cause for this is unknown.

These types of cancer can often be prevented by managing the risks of infection and disease progression in the AAPI population. And, importantly, different cancer prevention and screening strategies are needed for this ethnically diverse group.

What people in AAPI communities should know about their individual cancer risk

Since the current AAPI population includes many recent immigrants, those of us in AAPI communities need to take the initiative of writing down our own family histories of known cancer risks. When writing this history down and talking with members of your family, some questions to ask include:

-

Who in our extended family has had cancer?

-

What type of cancer did they have?

-

At what age were they diagnosed with cancer?

-

How well did cancer treatment work for them?

Knowing the cancer statistics from the country or community that you or your family came from can also help. For example, liver cancer causes close to 12% of cancer deaths in the Philippines. So, it would be prudent for people who have come from the Philippines to know their hepatitis B status and get timely vaccination. In fact, hepatitis B vaccination is recommended for all adults ages 19 to 59.

Additionally, Japanese and Chinese men may be at higher risk for colon cancer, so they should talk with their doctors about whether to start screening for colon cancer earlier than general recommendations. Women in Asia also have a higher risk for cervical cancer. So, when receiving HPV screening, AAPI women should ask if the screening will look for Asian-prevalent high-risk HPV variants. Current HPV vaccines for adolescents in the United States already cover such high-risk strains.

You should also talk with your doctor about what steps you can take to help lower your cancer risk. For example, to help lower the risk of gastric cancer, you may be able to change how you share food, which can help lower the risk of transmitting H. pylori bacteria. Thankfully, antibiotic treatments can destroy these germs if you test positive for them. Those with a family history of gastric cancer—especially if someone in the family was diagnosed before the age of 40—might also want to consult with their doctor about whether to get screened for gastric cancer.

The importance of cancer screening in AAPI communities

For people in AAPI communities, there might be a culture-related tendency for many of us to avoid talking about our cancer risk, as if the topic were a bad omen. Some AAPI people with cancer even feel ashamed about getting cancer, as if the disease was retribution for their past sins. However, these perceptions are not fact-based. Cancer is just what happens when some random cells in our body have gone wild, and our immune system was unable to detect and kill them. However, it is important that we find these bad cells early to help us live on after a cancer diagnosis.

Many of the types of cancer that Asian Americans are at greater risk for are rare in the general U.S. population, and doctors may be less familiar with how to treat them. It is important that those of us in the AAPI population receive tailored cancer screening recommendations based on our diverse ethnic backgrounds. Talk with your doctor about what types of cancer screening are recommended for you. We also need to be vocal about raising awareness around prevention of Asian-prevalent cancers, and we need to ask for resources to create better guidelines for both cancer screening and treatment.

Some insurance policies may not currently offer coverage for AAPI-tailored cancer screening services in the United States. One option may be to receive this screening in Asian countries where such services are available, but this option may not be feasible for many people. Because of this, it is important that more high-quality, cross-border clinical studies in Asia are conducted and that we support them. Studies like this could provide evidence to support AAPI-related screening and treatment options here in the United States, where certain cancer types that largely affect the AAPI population are still considered rare. Personally, I have benefited from working on a global oncology project in Asia where I was diagnosed with a high-risk thyroid cancer and treated with success.

Addressing barriers for AAPI people with cancer

One significant issue for AAPI people with cancer in trying to access quality cancer care is when they face a language barrier. AAPI people with cancer speak dozens of different languages, if not more dialects. This language factor alone may render us a “silent minority” if it is not better addressed.

It is important to advocate for resources to better reach out to AAPI communities and educate them about cancer prevention and screening, and to better help people with cancer and their caregivers navigate our medical and insurance systems. You can also talk with your health care team about what types of translation services or resources may be available to you or a loved one.

There are several resources that are currently available to help support AAPI people with cancer. For example, Cancer GRACE offers patient education materials in different languages. There are also patient advocacy associations focused on cancer types that predominantly affect AAPI people, including the American Liver Foundation and Blue Faery. It is my hope that new initiatives will focus on coordination between AAPI cancer advocacy groups in the United States and in Asian countries to better share our knowledge of patient education materials in various languages or dialects. Through this type of coordination, we can help make these materials as accessible to our communities as possible.