, by NCI Staff

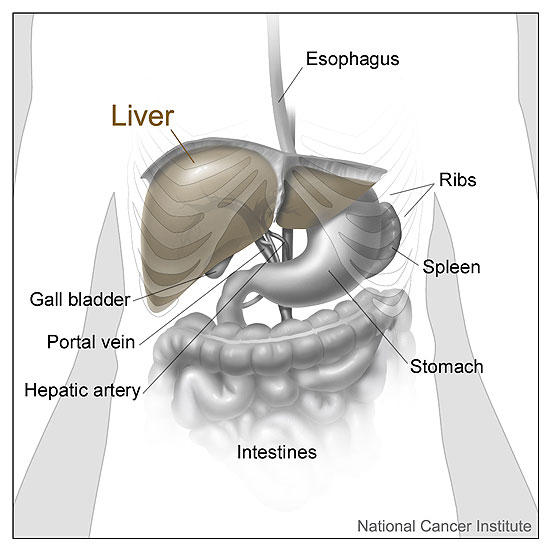

For the first time in nearly 13 years, there is a new treatment available that appears to be better than a standard therapy for people with a type of liver cancer called hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). On May 29, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved atezolizumab (Tecentriq) and bevacizumab (Avastin) as an initial treatment for people with liver cancer that has spread or that can’t be treated with surgery.

In the study that led to the approval, called IMbrave150, liver cancer patients treated with atezolizumab and bevacizumab lived substantially longer than those treated with sorafenib (Nexavar). They also lived longer without their cancer getting worse. The study findings were published May 14 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“This is a huge advance for patients,” said one of the study scientists, Richard Finn, M.D., of the University of California, Los Angeles. “This has been something that doctors who treat these patients have wanted for a long time, and this is a significant improvement.”

Atezolizumab is an immune checkpoint inhibitor, a type of treatment that helps the immune system seek out and destroy cancer. Bevacizumab is a targeted therapy that starves tumors by preventing new blood vessels from growing.

Sorafenib is another targeted therapy that blocks the growth of blood vessels and cancer cells. In 2007, sorafenib became the first drug approved by the FDA to treat some patients with HCC.

Until now, the only treatments for HCC that have been approved since 2007 are no more effective than sorafenib, said Tim Greten, M.D., deputy chief of the Thoracic and GI Malignancies Branch of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research.

And not only is the atezolizumab–bevacizumab combination more effective, it also led to “strikingly better patient-reported outcomes,” such as physical abilities, Robin Kelley, M.D., of the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, wrote in an editorial.

The combination regimen will likely replace sorafenib as the standard initial treatment for some people with advanced HCC, Dr. Greten said.

Adding on to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

Liver cancer is often diagnosed when it has already spread beyond the liver or is intertwined with many blood vessels, preventing it from being treated with surgery.

For people with liver cancer that can’t be treated with surgery (is inoperable), sorafenib and lenvatinib (Lenvima)—another drug that blocks blood vessel growth—are the only options for initial treatment.

A handful of clinical studies have tested immune checkpoint inhibitors as initial treatments for liver cancer but found that they didn’t work well on their own. With some more digging, scientists later found that high levels of a protein called VEGF may prevent immune checkpoint inhibitors from working.

VEGF stimulates the growth of new blood vessels and also changes the number and type of immune system cells in and around tumors, Dr. Finn explained.

Because bevacizumab blocks VEGF, researchers from Genentech and several different medical centers tested atezolizumab with bevacizumab in a small study of people with liver cancer. In 2019, they reported that the combination was more effective than atezolizumab alone and had tolerable side effects. The IMbrave150 trial is a follow-up to that earlier study.

Findings from the IMbrave150 Trial

The IMbrave150 trial, sponsored by F. Hoffman–La Roche/Genentech, involved more than 500 people with HCC. All participants had inoperable tumors and none had received whole-body (systemic) cancer treatment before.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive sorafenib or atezolizumab plus bevacizumab until the treatment stopped working or until the side effects became too harsh.

By all measures, the combination treatment worked better than sorafenib. More people who were treated with the combination than with sorafenib were still alive after 1 year: 67% in the combination group and 55% in the sorafenib group.

The length of time that half of the patients in a treatment group are still alive, called median overall survival, is a key measure of how well a treatment works. The median overall survival was 13 months in the sorafenib group and longer in the combination group.

The exact duration is still being determined for atezolizumab plus bevacizumab because most of the patients in that group are still alive, Dr. Greten noted.

Patients who received the combination treatment also lived 3 months longer without their cancer getting worse or dying (7 months versus 4 months for sorafenib).

The treatment worked—meaning it shrank tumors—for more patients who received the combination than sorafenib (27% versus 12%). That “is the highest reported [response] rate in a phase 3 trial for hepatocellular carcinoma to date,” Dr. Kelley noted.

In addition, far more patients in the combination group had a complete response, meaning all signs of cancer disappeared completely (6% versus 0% in the sorafenib group).

Although complete responses are noteworthy, “the more important point is how long patients actually benefit from the treatment,” Dr. Greten said. The treatment worked for longer than 6 months in 88% of people in the combination group and in 59% of those in the sorafenib group.

Patients in both treatment groups reported that their quality of life got worse during the study period. But people treated with the atezolizumab‒bevacizumab combination reported that their quality of life was preserved for considerably longer, about 7 months more than those treated with sorafenib.

“The goal with incurable cancers is to extend survival and maintain quality of life,” Dr. Finn stressed. In the studies that led to sorafenib’s approval, it didn’t improve quality of life over a placebo treatment, he added.

Safety of Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab

Many patients experienced side effects from the combination treatment. But overall, patients appeared to tolerate both drugs, Dr. Greten said.

There were similar rates of side effects and deaths due to side effects in the two groups. But more patients in the combination group had any serious side effects (38% versus 31%).

Fewer patients in the combination group paused or changed the dose of the treatments because of side effects (50% versus 61% in the sorafenib group). And although more patients in the combination group stopped taking one of the drugs (16% versus 10%), only 7% stopped taking both drugs because of side effects.

Bevacizumab can cause bleeding because of its effects on blood vessels, Dr. Greten explained. Liver cancer can also cause changes that heighten the risk of bleeding, such as low numbers of platelets, he added.

“There were a few more bleeding events in the atezolizumab‒bevacizumab arm, but still, as a percentage, it’s very low,” Dr. Finn said. Six percent of patients in both groups had serious bleeding events related to bevacizumab treatment.

“It will be important to identify the right patient population” for the combination treatment, Dr. Greten said. Patients may have to get routine tests to check for bleeding risk factors before taking the treatment, he suggested.

“Alternative therapies should be considered for patients at high risk for bleeding,” Dr. Kelley wrote.

More Combination Treatments Likely to Come

Many ongoing studies of HCC are testing combinations of an immune checkpoint inhibitor and a drug that targets blood vessels, such as pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and lenvatinib, Dr. Finn said. Other studies are testing combinations of immune checkpoint inhibitors, Dr. Kelley noted.

“We’ve made a huge step [with this study],” Dr. Finn said. But he and his colleagues are already thinking about how to continue to improve liver cancer treatment. “The question now is, what do we add on to bevacizumab and atezolizumab?”

Another future goal is to find biological markers (biomarkers), like the level of a blood protein, that doctors can use to figure out which patients are most likely to respond to immune checkpoint inhibitors that are part of a combination treatment. In general, immune checkpoint inhibitors are only effective for a fraction of patients with liver cancer.

“It would be helpful if you could actually identify the patients” who are likely to benefit from the treatment, Dr. Greten said. One of the ongoing goals of NCI’s Liver Cancer Program, of which Dr. Greten is the codirector, is identifying biomarkers for immunotherapy.