, by Linda Wang

For people with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) who are in remission, even when there is no trace of their disease, adding blinatumomab (Blincyto) to their treatment can help them live longer, results from a large clinical trial show.

In the trial, combining blinatumomab with chemotherapy substantially improved how long people whose cancer was in remission lived compared with those who got chemotherapy alone, which is the current standard therapy. In addition to being in remission, patients in the trial had no sign of their cancer, also known as minimal residual disease (MRD)-negative ALL.

Findings from the trial were presented in December 2022 at the American Society of Hematology (ASH) annual meeting in New Orleans.

In 2018, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved blinatumomab to treat people in remission but who still had signs of cancer in follow-up testing, also known as MRD-positive ALL. Although recurrences after remission are always a possibility, people with MRD-positive ALL after their initial treatment have a higher risk of their disease coming back than those who are MRD negative.

The results presented at the ASH meeting were for people who were MRD negative after their initial, or first-line, treatment.

At 3.5 years after starting postremission therapy, 83% of patients treated with blinatumomab and chemotherapy were still alive, compared with 65% of patients treated with chemotherapy alone.

“These results represent a new standard of care for this group of MRD-negative patients,” study leader Mark Litzow, M.D., of the Mayo Clinic, said during a presentation at the ASH meeting.

“The findings are a reminder that undetectable minimal residual disease does not mean that there is no disease left,” said study coauthor Richard Little, M.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis. “This very low level of disease that is responsible for relapse can be successfully eradicated in many cases by the addition of an immunotherapy component like blinatumomab.”

Blinatumomab effective for MRD-negative ALL as well

An aggressive type of blood cancer, B-cell ALL is the most common form of ALL in both adults and children. Chemotherapy is the standard treatment and often leads to remission, but many patients relapse, even those whose follow-up testing show no signs of disease.

Immunotherapy drugs have shown some promise as postremission treatment to decrease the risk of relapse.

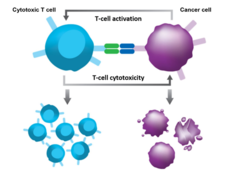

Blinatumomab is a type of immunotherapy called a bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE). It simultaneously attaches to T cells and cancer cells, enabling T cells to easily find and destroy the cancer cell by bringing them closer together. The drug, which is given intravenously, has been shown to be more effective than chemotherapy in treating children and young adults with B-ALL that has come back after initial treatment.

This trial, conducted by the NCI-supported ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group, was launched in 2013 to see if blinatumomab would be effective in treating adults newly diagnosed with B-cell ALL.

Although the trial enrolled 488 patients overall, the results presented at ASH were just for the 224 participants who were in remission and MRD-negative after the standard initial chemotherapy regimens. Those patients were randomly assigned to additional chemotherapy along with blinatumomab or just chemotherapy alone. All participants then received 2.5 years of maintenance chemotherapy. Some patients also received a bone marrow transplant at the discretion of their doctor.

In addition to improving overall survival, adding blinatumomab to chemotherapy improved how long patients lived without their disease coming back compared to those treated with chemotherapy alone.

No unexpected side effects were seen among the patients who received blinatumomab, Dr. Litzow reported. Common side effects associated with blinatumomab include fever, infusion-related reactions, headaches, infections, tremor, and chills.

Opening the door for less toxic chemotherapy alternatives

“The results are extremely exciting and impressive,” said Wendy Stock, M.D., of the University of Chicago, who was not involved in the design of the study but did enroll some patients on it.

“It suggests that adult patients with B-cell ALL who achieve MRD-negative status after aggressive combination chemotherapy can still benefit significantly from the addition of blinatumomab to postremission therapy,” Dr. Stock continued. “The study also shows that our techniques for detecting minimal residual disease in ALL are still not perfect.”

During his presentation at the ASH meeting, Dr. Litzow acknowledged that many of the patients who were initially enrolled in the trial could not continue in the study because chemotherapy didn’t help them achieve complete remission, which was a requirement for continued participation.

“It certainly raises the question of, ‘Should we be [using] immunotherapy earlier in the course [of treatment]?’” he said.

Another question that remains, he continued, is whether blinatumomab can be combined with other targeted therapies to further improve outcomes in people with ALL. Some studies are already trying to get that answer.

One small trial, for example, is testing blinatumomab along with the targeted therapy inotuzumab (Besponsa) and chemotherapy in people with newly diagnosed B-cell ALL. Although there are still many more studies to be done, Dr. Stock said, it’s clear that blinatumomab is helping patients in remission with B-cell ALL live longer.

“Five-year survival rates now approach over 80% in that patient population, which is wonderful,” Dr. Stock said. “Just 10 years ago, we were quoting rates of about 45% to 50% for this population, at best.”