, by NCI Staff

Oliver Bogler, Ph.D., joined NCI as the director of the Center for Cancer Training (CCT) in January. CCT develops training and career development programs that help build the next generation of diverse cancer researchers, both within NCI (intramurally) and around the country (extramurally). We interviewed Dr. Bogler about his move to NCI and his goals for CCT.

What drew you to this position?

My background is in basic cancer research, but I’ve been engaged in training and career development since 2007. I trained a handful of people in my own lab, and in one of my previous roles at a cancer center, I initiated a small grant program to stimulate collaborative research. So, I was interested in both the intramural and the extramural focuses and roles of CCT. And, of course, to work at NCI is a privilege for anyone. Those are the combinations of things that prompted me to come and work with this great team.

What are your goals for CCT?

I inherited from my predecessor, Dr. Jonathan Wiest, a well-functioning team that is doing really good work. My goals are to build on that track record and success. Regarding our intramural trainees, I’m very interested in providing them with the best training environment possible.

Right now, I’m focused on learning from our students and fellows what their needs and goals are. And then I think we can explore how we can, for example, harness current information tech to make the many learning opportunities more accessible and build connections across the large and dispersed training community at NCI.

I also want to deepen and perhaps extend the amount of information and data we have to make decisions and answer questions such as, how do we know a given training program is working optimally? Are we training the right people? Are we training them in the right way? Are we providing them with everything they need? Are we supporting them in all the critical stages in their launch towards the career they wish to be in?

Another thing I want CCT to do more of is collaborate and build relationships across NCI. I see lots of opportunities. We are already well connected with NCI’s Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities, and we work together with the other training programs at NCI. I’d like to find [more] ways for CCT to be a partner across NCI.

What are the challenges of assessing CCT programs?

One of the challenges is tracking trainees and figuring out if a training program or award has been successful. If you train someone at the junior end of their [career] path today, it will take years before you can assess where they have ended up and what they are doing. It’s like a long-term clinical trial. We have to be patient and see what works and what doesn’t.

If a trainee stays in biomedicine and applies for [NCI] grants, then we can readily follow them. If they publish scientific literature, we can follow them. What we are struggling with is trainees who go into other disciplines—those who shift to industry or science-related activities like science journalism, science policy, or science education. It’s much harder for us to track them. We’re brainstorming right now about how to follow those people.

We live in a data age, and you could imagine potentially collaborating with external entities—LinkedIn, for example. If we could find a way to track people through those kinds of platforms, it would allow us to unlock a huge amount of data to know where our alums go and how we can celebrate their successes and fine-tune our programs to meet their needs and the needs of cancer research workforce as a whole.

Who makes up the “cancer research workforce”?

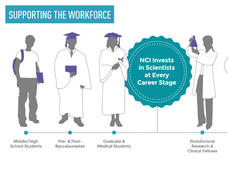

Many different people make up the cancer research workforce, but NCI’s primary focus is on cancer investigators. That includes Ph.D. scientists, but it also includes clinical scientists—doctors of various disciplines, nurses, physician assistants, and others who have an interest in both clinical care and research.

We have about 1,000 trainees at NCI in a given year. We know that about 30% will end up in traditional cancer investigator positions. But many of the others will go into other positions in science-related careers.

NCI’s priority is investigators, but I take a holistic view. People can make amazing contributions to cancer research and science in general without becoming an independent investigator. For instance, I believe that we need skilled science communicators to foster a cancer science-literate society that understands the value of cancer research.

What are the challenges for people entering cancer research today?

One challenge is that training in biomedicine has become more complex and more demanding. To be an effective cancer investigator now requires you to have knowledge across many fields and skills in many different areas. So, the training has become longer and more arduous.

Another challenge is that there are potential points of failure at transitions along the path to becoming an independent cancer researcher, such as getting your first faculty-level position and becoming a fully funded investigator. So how do we find the best people, bring them into the field, sustain them, and then launch them toward their independence as effectively and quickly as possible?

How does CCT support scientists during those difficult transitions?

There are many critical points on the path to becoming a scientist, but there is none more challenging than establishing yourself as an independent investigator. In our terminology, that is defined as someone who gets their first major grant for which they are the principal investigator or one of several principal investigators.

To get to that point, there is another critical point that immediately precedes it, which is to get a faculty position or an independent investigator position. Those two critical points are interconnected. To be competitive for a major grant, like an R01, you need a position that shows your independence, and increasingly getting such a position depends on a demonstrated track record of funding.

A few years ago, NIH introduced the Pathway to Independence Award to ease the transition through those two critical points. We identify someone during their postdoctoral training who has strong promise and give them some career development support with the K99 phase, and then give them an initial major grant with the R00 phase once they have transitioned into a faculty position. People with [these awards] get a running start in their efforts to launch their independent research and are very attractive to institutions that are searching for talent to add to their faculty.

There’s another training award that does the same thing for the graduate student-to-postdoc transition, the F99/K00. These kinds of awards are stepping-stones on the path from training to independence that we are trying to build to launch people into successful scientific careers.

Cancer research is changing so quickly. How do training programs keep up?

We need to think more broadly. Maybe we need to create environments where individuals can pick and choose from a broader offering of different kinds of science to put together a knowledge and skill base that helps them answer the questions they would like to answer, rather than training programs that have a particular predetermined path.

In addition to training people in traditional biology fields, there are other fields that we need to tap into, like data science, physical sciences, and artificial intelligence. Right now, we’re not making training in those fields part of the fundamental training of biologists. But if they were included, then we might unlock some potential to accelerate progress.

We have a couple of mechanisms that allow people to do that kind of training, including mechanisms that allow, for example, an established scientist to get support for additional training in an area like data science. It’s certainly an area where we can do more, and we can do better. You could imagine training programs for cancer biologists being enhanced and extended or new programs being created. That is a really good example of the kinds of things we need to be doing and will be exploring in the coming years.

CCT also focuses on diversity. Why is it important to have diversity in the cancer research workforce?

I think it is essential to NCI and CCT’s missions. Without expanding the inclusiveness of our training programs to expand the inclusiveness of our cancer research community, we are leaving a lot of talented people out, and that’s to the detriment of everyone.

There are still some big gaps in our understanding of cancer. For example, we know a lot more about medical conditions in white men than we do in any other group, and that’s obviously not sufficient. I believe a diverse cancer research workforce will do the most comprehensive cancer research and help fill in those gaps. We want anyone who has talent and has the desire to join the fight against cancer to be able to do that.

Does CCT support training for nonresearch careers?

At NCI we have programs that offer trainees the opportunity to explore nonresearch careers. For example, we have the Explore on Site (EXPOSE) program where NCI postdoctoral fellows go on external site visits to local companies and organizations spanning multiple sectors, from pharmaceutical companies to government organizations.

Also, we have the Preparing for Science-Based Non-Traditional Careers course where representatives from various companies come and share their experiences and individual journeys while describing best practices for getting a job and navigating unique challenges.

We also do workforce development training to help our trainees develop some of the skills needed to transition into non-academic careers. For example, we have a program where people learn how to do an elevator pitch—a succinct way of describing a complex research project in a compelling way in a minute and a half. That’s just one example of the kinds of skills we are training folks in.

While our primary focus is the training of cancer investigators, we see opportunities to contribute to the broader workforce and to help the people that chose NCI as a place to be trained reach their goals.