, by Linda Wang

Radiation combined with chemotherapy, also known as chemoradiotherapy, is routinely given to people with rectal cancer whose tumors can be removed with surgery. The treatment can shrink tumors, making it easier to remove the entire tumor and helping to prevent the disease from coming back.

Now, results from a large NCI-funded clinical trial suggest that radiation may not be needed before surgery for all people with this form of rectal cancer, which is called locally advanced because it has spread within the rectum but not to other organs. A newer form of combination chemotherapy ahead of surgery appears to be just as effective as chemoradiotherapy at keeping the disease at bay, the trial showed.

“This is practice changing,” said Deborah Schrag, M.D., of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, who led the study.

Patients with specific clinical stages of rectal cancer may be able to safely skip radiation, Dr. Schrag continued. “And if you don’t get radiation, you’re not going to have the long-term adverse effects of radiation, which may be very important to some people. Globally this is important because in some countries access to radiation is very scarce.”

In the trial, called PROSPECT, nearly 1,200 people with locally advanced rectal cancer were randomly assigned to receive either a chemotherapy regimen called FOLFOX or chemoradiotherapy, which uses just one chemotherapy drug, before surgery.

After a median follow-up of nearly 5 years after surgery, 81% of people in the FOLFOX group were still alive with no signs of cancer (known as disease-free survival), compared with 79% of people in the chemoradiotherapy group, Dr. Schrag reported at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting in June. The study results were simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

During treatment, people in the chemoradiotherapy group reported fewer side effects than people in the FOLFOX group. However, one year after surgery, people in the FOLFOX group reported fewer side effects than those in the chemoradiotherapy group. Those results were published separately June 4 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“What PROSPECT gives us is an alternative,” said Carmen Allegra, M.D., who works with NCI’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program and was not involved in the trial. “Patients now have an option other than chemoradiotherapy.”

Younger people who want to avoid the harmful effects of radiation on fertility might opt for FOLFOX, while someone who can’t tolerate the side effects of FOLFOX might choose chemoradiotherapy instead, Dr. Allegra said.

Questioning the need for radiation

Globally, around 800,000 people will be diagnosed with rectal cancer in 2023, and about half with locally advanced tumors.

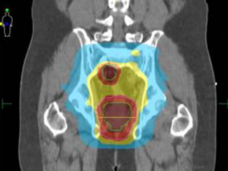

For more than 3 decades, chemoradiotherapy before surgery, called neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, has been standard treatment in the United States for people with locally advanced rectal cancer. The treatment, when combined with modern surgical techniques, is very effective. But pelvic radiation comes with many short- and long-term side effects, such as impaired bladder, bowel, and sexual function; pelvic fractures; and secondary cancers.

In recent years, multidrug chemotherapy regimens like FOLFOX have become a standard postsurgical (adjuvant) treatment for people with locally advanced rectal cancer. In addition, colorectal cancer screening rates have improved, leading to earlier diagnoses. Surgical techniques and methods for ensuring that patients’ cancers are accurately diagnosed so they get the most effective and appropriate treatment have also improved.

“All these other things got better, but we just kept doing [neoadjuvant] radiation,” Dr. Schrag said. “It was time to try to capitalize on those advances.”

So she and her colleagues set out to answer some critical questions: Could neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy be omitted for patients who respond to combination chemotherapy without increasing the risk of recurrence? And how do the two treatment options compare with respect to side effects?

Following promising results from a pilot study of FOLFOX before surgery in people with this stage of disease, Dr. Schrag and her colleagues launched PROSPECT to compare these options head-to-head.

Similar outcomes with chemotherapy alone

In PROSPECT, which was conducted by the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology, researchers randomly assigned 1,194 people with locally advanced rectal cancer (stages T2 or T3 involving lymph nodes and T3 not involving lymph nodes) to receive either pelvic chemoradiotherapy or six cycles of FOLFOX before surgery. Adjuvant chemotherapy was recommended but not required.

The study was a noninferiority trial, meaning it was designed to test whether neoadjuvant FOLFOX would be no less effective than neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for people with tumors that weren’t at high risk of spreading.

After almost 5 years, cancer-specific outcomes between the FOLFOX and chemoradiotherapy groups were very similar. In addition to patients in both groups having nearly identical disease-free survival, they also had nearly the same outcomes for other cancer-related findings, including their 5-year overall survival and the return of the cancer in the rectum.

For those in the FOLFOX group who had serious side effects or whose tumors shrank by less than 20%, chemoradiotherapy was given ahead of surgery. Only 9% of people in the FOLFOX group went on to receive neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy.

When it came to side effects, there were notable differences between the groups with respect to timing. During treatment, for example, fewer people in the chemoradiotherapy group reported effects, such as appetite loss, constipation, fatigue, and neuropathy, than people in the FOLFOX group.

However, a year after surgery, the pattern had reversed, with fewer people in the FOLFOX group reporting lingering side effects than people in the chemoradiotherapy group. Participants in both groups reported similar overall quality of life during and after treatment.

Empowering people with more options

According to Corrie Marijnen, M.D., Ph.D., of the Netherlands Cancer Institute, who commented on the study at the ASCO meeting, guidelines for treating locally advanced rectal cancers vary in different parts of the world. For example, in Europe, neoadjuvant treatment is generally only used in people with what are considered to be high-risk tumors. So PROSPECT’s findings will likely apply largely to people being treated in North America, she said.

In addition, she noted, new approaches to treating rectal cancer have emerged since the trial launched in 2012.

One approach being evaluated is total neoadjuvant therapy, which incorporates chemotherapy with chemoradiotherapy before surgery. In some cases, total neoadjuvant therapy can help some patients avoid surgery altogether.

Other studies are testing immunotherapy, particularly in people with locally advanced rectal cancer that has specific genetic changes. In one recent study of 12 people with rectal cancer whose tumors had these changes, the immune checkpoint inhibitor dostarlimab led to complete tumor shrinkage in every patient. According to updated data from the trial presented earlier this year, 30 patients have been treated and all 30 had their tumor completely disappear.

In the meantime, for many people with locally advanced rectal cancer, being able to avoid the effects of radiation can be empowering, Dr. Allegra said.

“Before PROSPECT, we didn’t [know if it was] safe to not give radiation,” he said. “Now we know, yes, there’s a safe way to skip radiation, if that’s your preference. There are a lot of factors that go into that decision, but at least you have the opportunity to make that decision.”