, by NCI Staff

The Oncotype DX test, which helps guide treatment decisions for women with early-stage breast cancer, may be less accurate for Black women than for non-Hispanic White women, a new study suggests.

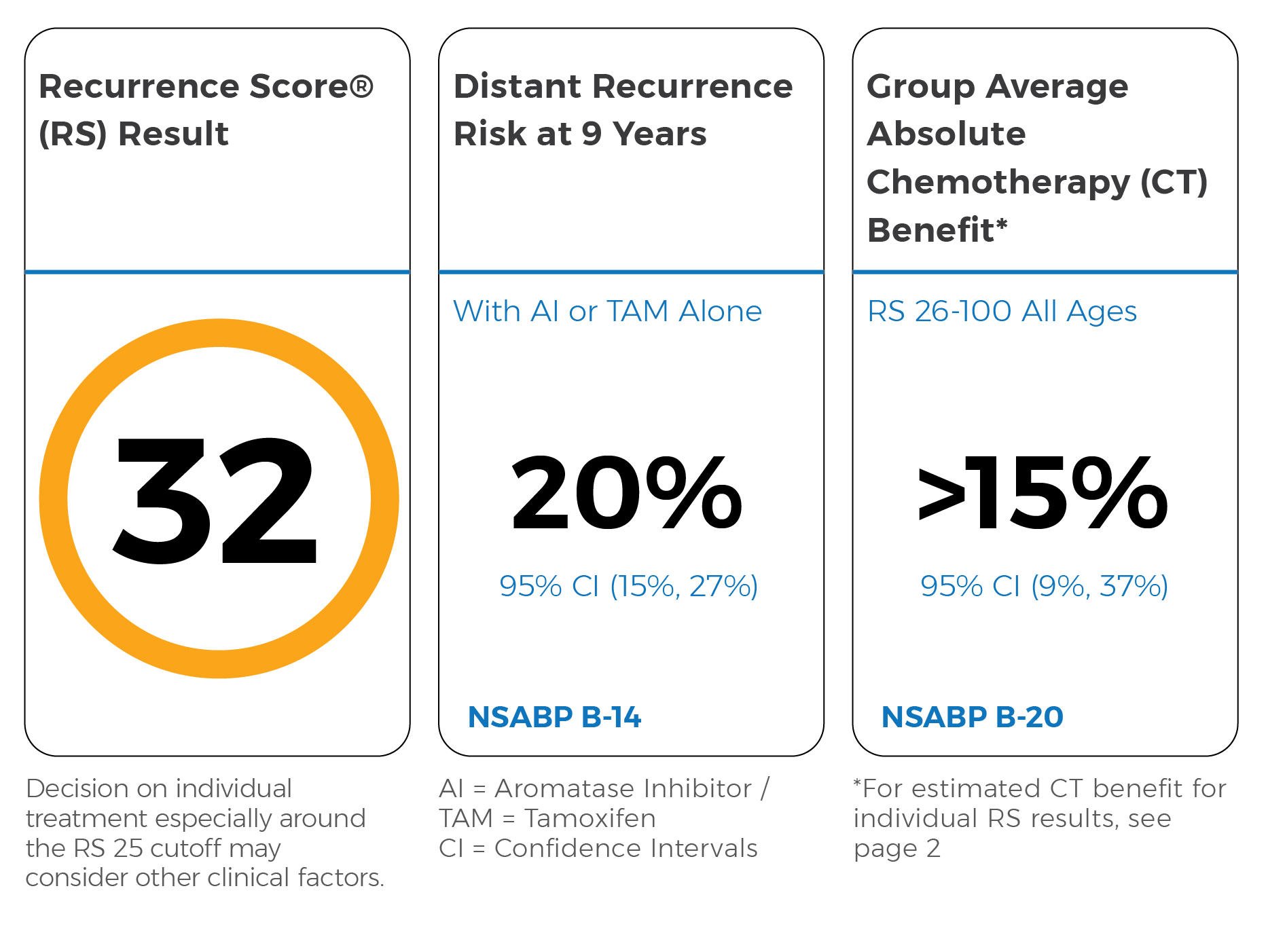

The test measures how aggressive a woman’s breast cancer is and helps her and her doctor decide if she should get chemotherapy after surgery. Oncotype DX works by looking at the activity of a group of genes in the tumor and calculating a score between 0 and 100. The score predicts the risk of the cancer coming back, which can help gauge the patient’s risk of dying from breast cancer.

The new study showed that, overall, Black women had higher Oncotype DX scores than White women. And among women with similar scores, Blacks were more likely than Whites to die of breast cancer. The researchers also determined that the test was not as good at predicting the risk of breast cancer death for Black women, according to the results published January 21 in JAMA Oncology.

These findings “raise the question of whether the test is less accurate [at] identifying which [Black] patients need chemotherapy,” noted the study’s leader, Kent Hoskins, M.D., of the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Dr. Hoskins and his colleagues are currently exploring that question. But until then, current medical practices for recommending chemotherapy based on Oncotype DX scores shouldn’t change, he said.

“The larger message here,” Dr. Hoskins stressed, “is that as we develop new tests like this, it’s really important that the study populations have greater racial diversity because there really can be differences that influence the performance of these tests.”

“That’s a broader problem in biomedical research in general—underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minority groups,” he added.

Does Oncotype DX Work for Everyone?

The Oncotype DX test is widely used to guide treatment decisions for people with a type of early-stage breast cancer, known as ER positive or hormone receptor positive.

But relatively few Black women participated in the studies that were done to develop and validate the test, Dr. Hoskins explained. That made the researchers wonder how well the test actually performs in Black women, he said.

The team looked at data from a specialized database developed by NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. The database includes information on more than 86,000 breast cancer patients from across the country who had Oncotype DX test results available. About 74% were White, 8% were Black, and 9% were Hispanic. All of the women had early-stage ER-positive breast cancer.

Black women were more likely than non-Hispanic White women to have a high score (greater than 25) on the Oncotype DX test, the scientists found. But even after taking into account age, tumor size, and whether there was cancer in the lymph nodes—factors that are linked with more aggressive breast cancer—Black women were still more likely to have a higher Oncotype DX score.

That finding “tells us that Black women, for unknown reasons, develop biologically more aggressive tumors. We don’t know why that is and that’s one of the areas we’re investigating,” Dr. Hoskins noted. NCI’s Breast Cancer Genetic Study in African-Ancestry Populations is also exploring how genetics and biology contribute to breast cancer outcomes among Black women.

Tumor characteristics (such as certain genetic changes or immune system changes) that might occur more frequently in Black women may be missed by Oncotype DX because the test was developed using very little information from Black patients, pointed out Christopher Li, M.D., Ph.D., of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, an expert on breast cancer disparities who was not involved in the work.

Biggest Disparity for Lowest Risk Cancers

Oncotype DX scores are grouped into three categories that reflect a patient’s risk of their cancer returning. Scores under 10 indicate a low risk, while those between 11 and 25 are intermediate risk, and scores 26 and above are considered high risk.

Most patients with low and intermediate risk scores get hormone therapy after surgery, whereas those with high scores get chemotherapy in addition to hormone therapy.

Within all three risk groups, Black women were more likely than Whites to die of breast cancer during the follow-up period (a median of 4.5 years), the research team found. This pattern was seen only in women with breast cancer that hadn’t spread to the lymph nodes (what’s known as node-negative breast cancer).

Although there seemed to be no racial or ethnic differences in breast cancer death rates for women with cancer that had spread to the lymph nodes, there wasn’t enough data in this group to make a firm conclusion, Dr. Hoskins said.

For women with node-negative breast cancer, Blacks with low risk scores were more than twice as likely to die of breast cancer than Whites with low risk scores. Black women with intermediate or high scores were also more likely than Whites with similar scores to die of breast cancer, but the difference was slightly smaller (1.6 and 1.5 times more likely to die, respectively).

These results partially confirm preliminary findings from the TAILORx trial, a clinical study of more than 10,000 women who received breast cancer treatment based on Oncotype DX test results.

Dr. Hoskins and his colleagues also calculated how well Oncotype DX predicts the prognosis—specifically the risk of breast cancer death—for women with node-negative breast cancer in each racial/ethnic group. They found that the test had a lower accuracy for Black women than White women, meaning it was not as accurate at predicting death from breast cancer.

This finding suggests that the test may need to be “recalibrated” for Black patients, Dr. Hoskins explained. It’s possible that further studies may find that there “should be different cut points for recommending chemotherapy in racial/ethnic minority women,” he said.

Real World Data

Using NCI’s SEER database is a strength of the study because it captures data from the real world, Dr. Li noted.

But a caveat is that the database has only tracked participants for about 4.5 years, noted Joseph Sparano, M.D., and Otis Brawley, M.D., in an accompanying editorial. That’s a relatively short amount of time, Dr. Hoskins agreed, because ER-positive breast cancer can return up to 20 years after surgery.

Another limitation is that the database didn’t include information on whether the women took hormone therapy as prescribed. Studies have shown that Black women are more likely to skip doses of or stop taking hormone therapy, which can affect the risk of cancer recurrence and death from cancer.

The Root of Breast Cancer Disparities

There are many glaring differences between the outcomes of Black and White women with breast cancer. For example, Black women are more likely to be diagnosed with advanced cancer and to die from it.

This study “adds an additional layer to our understanding of breast cancer disparities,” Dr. Li said. “But we have yet to understand what factors are contributing to the differences observed,” he added.

The conditions where people are born, live, work, and play (known as the social determinants of health) “are clearly the root causes of health disparities and undoubtedly play a role in why we saw that mortality disparity in the study,” Dr. Hoskins said.

Greater poverty and segregation in communities, institutional racism, and limited access to high-quality medical care all contribute to unequal health outcomes for Black Americans, Drs. Sparano and Brawley noted. For breast cancer in particular, these factors can make it more likely for Black women to delay or stop treatment.

Biology and genetics likely contribute to breast cancer disparities, as well, the editorialists wrote. For example, women of African heritage have higher rates of certain side effects from chemotherapy, leading them to take lower doses.

Dr. Hoskins and his colleagues are delving into some of these possibilities. They’re currently taking a closer look at social determinants of health to see how they might be influencing Oncotype DX scores.