, by NCI Staff

Before a tumor spreads from its original location to other parts of the body, it typically invades nearby lymph nodes. For more than a century, researchers have debated whether this invasion of lymph nodes helps the cancer spread (or metastasize) to other organs.

A new study in mice suggests that it is an important step for cancer metastasis, and details how that happens.

Lymph nodes are bean-shaped organs that filter viruses, bacteria, and cancer cells out of the body. When you’re sick and the doctor feels the sides of your neck, they’re checking to see if your lymph nodes are swollen with immune cells fighting off an infection.

The study, partially funded by NCI’s Cancer Systems Biology Consortium, showed that cancer cells in the lymph nodes of mice encourage immune cells to protect tumors rather than attack them. As a result, the initial tumor essentially gains a pass to spread to the rest of the body.

The findings were published May 6 in Cell.

Cancer cells “not only avoid attack in the lymph nodes, but they actually turn things completely around and somehow convince the immune system to help the tumor spread,” explained the study’s senior scientist, Edgar Engleman, M.D., of Stanford Medicine.

Many studies have looked at the interplay of immune cells and cancer cells inside tumors, but these findings highlight “action happening somewhere else, outside of the metastatic and primary tumors,” said Hannah Dueck, Ph.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Biology. It highlights the role of the lymph nodes in the overall immune response to cancer, she said.

With some exceptions, the study was mostly carried out in mice implanted with melanoma, so additional studies are needed to see if the same phenomenon happens in people and with other kinds of cancer, Dr. Dueck noted.

What are lymph nodes?

“Lymph nodes are the heart and soul of the immune system,” Dr. Engleman said. But they haven’t gotten as much attention as they deserve, he added.

Lymph, a watery mixture of immune cells and fluid, flows through our bodies via a network of vein-like pipes. Hundreds of lymph nodes are dotted along this network.

Lymph nodes are like sophisticated training centers. Inside, immune cells learn how to fight infections and cancer. Once fully trained, the immune cells leave the lymph nodes to monitor the body for intruders.

To metastasize, cancer cells break off from the primary tumor and travel through the blood or lymph to other organs. If someone is found to have cancer in their lymph nodes, it’s usually a bad sign that the cancer has or will soon spread to other parts of the body. Most cancer deaths are caused by metastatic cancer.

But it’s never been clear what cancer cells are actually doing in the lymph nodes.

“One of the theories is that, in the lymph node, [cancer cells] gain traits that make them metastatic. And then, from there, they go to the distant organ,” Dr. Dueck explained.

“There is another theory that some cells from the tumor go to the lymph nodes, and some go to the distant organ,” she said. With this view, the lymph nodes don’t play a critical role in metastasis, she added.

With the necessary models and tools at their disposal, Dr. Engleman’s team set out to address the long-standing debate about these two theories.

Spreading to lymph nodes helps cancer metastasize

The researchers first asked whether cancer in the lymph nodes of mice helps tumors metastasize to the lungs, one of the most common places cancer spreads to.

They implanted groups of melanoma cells under the skin of mice and let them form tumors. In some mice, the cancer spread to the lymph nodes, and in other mice, it didn’t. After several weeks, the researchers injected melanoma cells that don’t spread to lymph nodes into the veins of the mice and then checked their lungs for cancer.

There were far more tumors in the lungs of mice that had cancer in their lymph nodes than in mice that didn’t, they found.

So, it appears that spreading to lymph nodes helps cancer metastasize to the lungs, Dr. Engleman said.

Cancer cells dodge attack on the way to lymph nodes

Next, the researchers asked what gives some melanoma cells the ability to spread to the lymph nodes.

They found that cancer cells that had spread to the lymph nodes had higher levels of certain proteins, including PD-L1 and MHC-I, than melanoma cells that didn’t spread. High levels of PD-L1 and MHC-I send signals that tell cancer-fighting immune cells not to attack.

Further studies confirmed that higher levels of PD-L1 and MHC-I shielded melanoma cells from attack by immune cells. More specifically, immune cells called NK cells killed fewer melanoma cells that spread to the lymph nodes than melanoma cells that didn’t spread.

“It’s quite remarkable what [cancer cells have] to dodge on the way to the lymph nodes. There is lots of immune attack,” Dr. Engleman explained.

Cancer highjacks the immune system

The researchers also explored what happens once cancer gets to the lymph nodes. Similar to what other studies have found, it appears that when cancer cells arrive, they shift the amounts and types of immune cells in the lymph nodes.

In mice, for example, there were fewer cancer-killing immune cells in lymph nodes that were invaded by melanoma than in lymph nodes that were cancer-free, the researchers found.

There were also more immune cells called T-regulatory cells (T-regs) in lymph nodes that were invaded by melanoma cells.

And in tissue samples from people with head and neck cancer, there were more T-regs in lymph nodes where cancer had invaded than in lymph nodes that were cancer-free.

The main role of T-regs is to protect healthy cells from attack by other immune cells that have gone off the rails. By doing so, T-regs help prevent autoimmune diseases and chronic inflammation. But T-regs can sometimes get mixed up, protecting unhealthy cells that should be eliminated, like cancer cells.

That’s exactly what the researchers appeared to see in their mouse studies: In mice that were bred to lack T-regs, melanoma tumors were less able to spread to the lungs.

The scientists then removed T-regs from the lymph nodes of mice where melanoma had or hadn’t invaded. They transferred the T-regs into other mice with melanoma that hadn’t invaded the lymph nodes. Only the T-regs from lymph nodes with cancer helped melanoma cells spread to the lungs, the researchers found.

Like other kinds of T cells, T-regs have special receptors that let them “recognize” the cells they protect. In mice with melanoma that invaded into lymph nodes, the researchers found T-regs that recognized the cancer cells.

In the near future, the team plans to examine exactly how cancer cells in the lymph nodes coax T-regs to protect them.

A new view of cancer metastasis

In the lymph nodes, immune cells learn what to attack (such as infected cells) and what to protect (such as healthy cells).

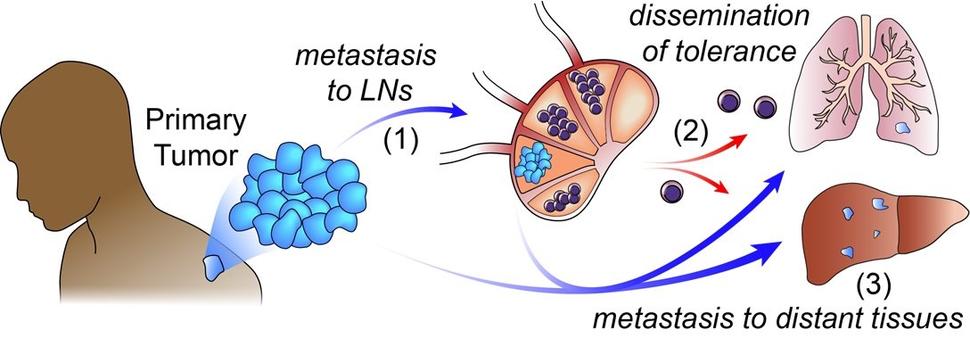

But this study suggests that, in lymph nodes invaded by cancer, immune cells learn to protect the cancer cells rather than attack them, Dr. Engleman said. This phenomenon is called immune tolerance.

The research team suspects that “those specialized [T-reg] cells—once they’re educated by the tumor—leave the lymph node, go all over the body, and instruct the immune system not to attack” other cancer cells, he explained.

If that’s the case, it would make distant organs more hospitable to the cancer, he said.

“Thus, we propose a new model of metastasis we call ‘Metastatic Tolerance,’” tweeted the study’s lead scientist, Nathan Reticker-Flynn, Ph.D., of Stanford University.

“There’s missing pieces about how exactly the T-regulatory cells get sent around the body,” Dr. Dueck noted. But the idea is that “there might be tolerance from the immune system by the time the [cancer] cells get to distant organs.”

With this new view of metastasis, the two prevailing theories on lymph nodes can be reconciled, Dr. Dueck explained. By spreading to lymph nodes and turning immune tolerance on, it’s easier for cancer cells in the primary tumor or in the lymph nodes to metastasize to distant organs.

Dr. Engleman and his team think it may be possible to develop therapies that switch off this tolerance. If used at the right time, such therapies could prevent cancer metastasis.

The findings could also prompt new research on cancer immunotherapies, Dr. Dueck noted. “In some cases, resistance to immunotherapy may involve some sort of effect in the lymph nodes. So, [the study findings] could also provide clues about ways to address resistance to immunotherapy,” she said.