December 27, 2018, by NCI Staff

Credit: iStock

Some older people diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) now have two new treatment options, with the approvals last month by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of two targeted therapies.

The drugs, venetoclax (Venclexta) and glasdegib (Daurismo), were approved for use in patients aged 75 and older and those who have health conditions that prevent them from receiving the intensive chemotherapy regimen that is the standard initial treatment for AML.

Both venetoclax and glasdegib were approved to be used in combination with other low-dose chemotherapy drugs already used to treat AML.

People over age 65 represent the majority of those diagnosed with AML, and patients who can’t tolerate the standard chemotherapy regimen—which can cause significant side effects—fare far worse than those who do receive it. So having two new treatment choices, both of which have proven effective in clinical trials involving older patients with AML, is critically important, said Eunice Wang, M.D., chief of the Leukemia Service at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo, New York.

Despite long-standing efforts to develop effective, safe therapies for this patient group, “too many times we’ve been disappointed,” Dr. Wang said. “With two new approved regimens … it really opens the door to being able to treat many more patients than we have in the past.”

Treatment Considerations for AML

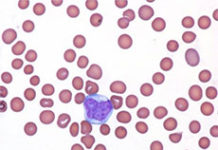

AML is a common form of leukemia in adults and is also among the most aggressive forms of the blood cancer. It is diagnosed most often in people in their late 60s, so by definition “it’s a disease of the elderly,” Dr. Wang said.

For patients who aren’t healthy enough to tolerate the standard initial chemotherapy regimen—typically called 7+3, for the days of the week on which the drugs in the regimen are delivered—AML is particularly fatal. Only approximately 5% of older patients or those deemed unfit to undergo intensive chemotherapy survive for at least 5 years following diagnosis, compared with 40% of those diagnosed at younger ages.

A patient may be unable to tolerate the standard regimen due to frailty or because of other health problems, including those related to having had myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or being treated for cancer in the past, explained Aric Hall, M.D., who specializes in the treatment of blood cancers at the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center. The biological characteristics of AML in older patients also often make their disease not likely to respond well to the 7+3 regimen.

But it is not always simple to determine whether an older patient is a candidate for intensive chemotherapy, Dr. Hall explained. To begin with, the 7+3 regimen, on its own, can almost never cure an older patient with AML, he said. For the best chance of long-term survival, Dr. Hall continued, those who have a complete remission following the treatment would go on to receive a stem cell transplant, which can induce a cure in a substantial portion of patients.

Some older or unwell patients may be willing to try the intensive 7+3 chemotherapy (even if it turns out that they cannot tolerate it) to see if they can then make it to a transplant. But the transplants can also be physically grueling and pose serious risks, including death.

“If I’m going to suggest putting them through that [chemotherapy], I first need to assess their transplant eligibility and their willingness” to undergo a transplant, he said. For those patients for whom a transplant isn’t a likelihood, Dr. Hall continued, “then I start thinking about low-intensity options, which can be used for a long period of time.”

In the past, many older or unfit patients have been directly referred for palliative care and hospice, Dr. Wang said. One study, in fact, found that more than half of people over age 65 diagnosed with AML never received any treatment for their cancer.

But over the last several years, there has been a shift in treatment patterns for such patients, Dr. Wang explained, particularly with the increased use of azacitidine (Vidaza) and decitabine (Dacogen)—chemotherapy drugs known as hypomethylating agents—as stand-alone options in these patients. Up to a quarter of older patients respond to these therapies, she noted, with some improvement in survival compared with other commonly used options.

At the same time, studies have shown that a number of cancer-related genes are commonly mutated in AML, leading researchers to begin investigating whether drugs that target some of these genes may be effective in older patients who aren’t candidates for intensive chemotherapy.

Glasdegib: Targeting the Hedgehog Signaling Pathway

One such gene is SMO, the target for glasdegib. FDA’s decision marks the first approval for glasdegib.

The SMO protein (also called smoothened) is a component of a signaling pathway in cells called Hedgehog that is often hyperactive in AML, fueling its growth and spread. The Hedgehog pathway is involved in the regulation of key functions of cancer stem cells, which have been linked to treatment resistance and cancer recurrence.

The trial that led to glasdegib’s approval, called BRIGHT AML 1003, enrolled 115 people with newly diagnosed AML who were not candidates for intensive chemotherapy. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either glasdegib, which is taken as a pill, in combination with low doses of the chemotherapy drug cytarabine or low-dose cytarabine alone. About half of the patients had what is called secondary AML, meaning disease that developed after prior MDS, or therapy-related AML, meaning it arose after treatment for a prior cancer.

The older patients with AML in the trial who received the glasdegib–chemotherapy combination had a substantial improvement in how long they lived overall compared with patients treated with chemotherapy alone: a median of 8.3 months versus 4.3 months.

Some of the most common side effects seen in patients treated with glasdegib included anemia, fatigue, and musculoskeletal pain. Although some patients experienced serious side effects, including pneumonia, hemorrhage, and low white blood cell count, Dr. Wang noted that the number and severity of these effects were much less than what is typically seen with intensive chemotherapy for AML.

Venetoclax: From CLL to AML

Venetoclax, which is already approved by FDA to treat some patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and is given by infusion in the hospital, kills leukemia cells by blocking the activity of BCL-2 proteins. These proteins, which are often overexpressed in AML cells, regulate a form of cell death called apoptosis. When there is too much BCL-2 in AML cells, it stymies the signals that would otherwise tell a cell to die.

The new approval of venetoclax for AML covers its use in combination with any of three different drugs: azacitidine, decitabine, or low-dose cytarabine. Studies have suggested that venetoclax works synergistically with these drugs—that is, the efficacy of each combination is greater than what would be expected from the additive effect of the individual drugs.

Whereas glasdegib was granted a regular approval by FDA, venetoclax was given an accelerated approval based on early data from clinical trials that strongly suggested the treatment will have a clinical benefit for patients. Under an accelerated approval, the treatment’s manufacturer must conduct a larger trial to confirm that the drug is both effective and safe. Two such trials are ongoing.

The venetoclax approval was based on results from two different early-phase clinical trials in which patients were age 75 and older and could not be treated with intensive induction chemotherapy.

In both trials, all patients were treated with venetoclax in combination with one of the three drugs. The rate of complete remissions following treatment ranged from approximately 20% (venetoclax plus low-dose cytarabine) to 54% (venetoclax plus decitabine). The duration of those remissions also varied; the median length was around 5 to 7 months, but some remissions in patients treated with venetoclax plus azacitidine lasted up to and, in some cases, beyond 2 years.

Anemia, nausea, and fatigue were among the most common side effects in both trials, with substantial decreases in white blood cell count the most common serious side effect.

Which Drug to Use?

With two new approvals for the same patient population, clinicians will have to decide which drug is the best choice for their patients. For many, Dr. Hall said, it may initially be venetoclax.

Because this drug is already approved for CLL, oncologists who treat blood cancers are familiar with venetoclax and, he added, some likely have already been using it off label to treat their older patients with AML.

Venetoclax can also be used in combination with azacitidine and decitabine, both of which clinicians in the United States already use frequently. Glasdegib, on the other hand, is approved for use with low-dose cytarabine, which is used commonly in Europe but much less so in the United States, he said.

Glasdegib “has been lower on the radar” of oncologists in the United States, he continued. Aside from those who have used it as part of a clinical trial in which they were involved, many clinicians have likely never used it.

“But it’s hard to get a survival improvement in older AML patients,” Dr. Hall said. “So clearly there is a role for it.”

Dr. Wang agreed that many clinicians will likely be more inclined to use venetoclax. But, she noted, glasdegib in combination with low-dose cytarabine (which is given via injection), both of which can be taken at home, may be preferable for some patients.

For more frail patients or those who have a hard time traveling, “their priority is often to be out of hospital,” she said.

Moving forward, Dr. Hall stressed that, although he welcomed these new treatment options, “they aren’t curative.” With the new choices, Dr. Hall also said he was concerned that some patients who could possibly tolerate intensive therapy and eventually be candidates for a stem cell transplant will receive venetoclax or glasdegib instead, and not be given the opportunity to consider transplant.

From a research perspective, Dr. Wang said studies are already ongoing to see if both drugs can be used as part of initial treatment of patients who are fit to receive intensive chemotherapy. For example, venetoclax is being tested in combination with 7+3 chemotherapy, she said, and other studies are testing these drugs in combination with other targeted agents.