, by NCI Staff

On December 18, 2019, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted accelerated approval to enfortumab vedotin-ejfv (Padcev) for people with advanced bladder cancer that has progressed despite treatment with two previous therapies.

Enfortumab vedotin was the second targeted drug to be approved for the treatment of advanced bladder cancer in 2019. Earlier in the year, FDA granted accelerated approval to erdafitinib (Balversa). However, erdafitnib can only be used to treat cancers that have an alteration in one of several genes called FGFR. Only about 20% of bladder cancers harbor an FGFR alteration.

“We have been desperately looking for a new treatment option for patients” with advanced, progressive disease, said Joaquim Bellmunt, M.D., Ph.D., who directs the Bladder Cancer Program at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

The approval of enfortumab vedotin was based on findings from a cohort of participants in a small clinical trial called EV-201 that enrolled people with metastatic bladder cancer. All 125 participants in the cohort had been treated with chemotherapy that used platinum-containing drugs (such as cisplatin and oxaliplatin) as their initial, or first-line, treatment. When their cancer progressed, an immune checkpoint inhibitor had been used as their second-line treatment.

All patients in the trial received enfortumab vedotin. Overall, 55 participants (44%) had their cancers shrink or stop growing during treatment. Fifteen of these had their tumors disappear entirely, known as a complete response. Responses to treatment lasted for a median of 7.6 months. The trial was funded by the drug’s manufacturers, Seattle Genetics and Astellas Pharma.

Currently, the standard third-line treatment for people with metastatic bladder cancer is chemotherapy that uses taxane agents, such as paclitaxel and docetaxel.

“And less than 10% of our patients actually have responses to these regimens,” said Tian Zhang, M.D., of Duke University, who is involved with another ongoing study of enfortumab vedotin. “We’ve seen some great responses [with enfortumab vedotin], and I’m really hopeful for a lot of my patients who might benefit from this drug.”

A Common Target

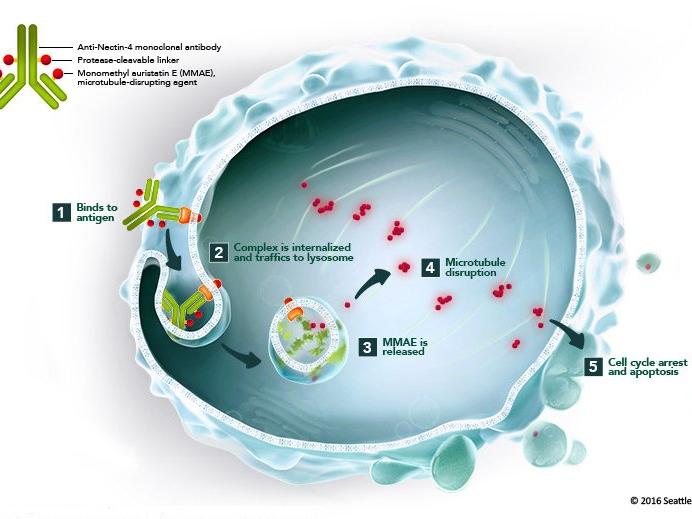

Enfortumab vedotin is a type of targeted therapy called an antibody‒drug conjugate. Antibody‒drug conjugates consist of a monoclonal antibody chemically linked to a drug.

The monoclonal antibody part of enfortumab vedotin binds to a protein called nectin-4, which is found on the surface of most bladder cancer cells. The antibody is chemically linked to monomethyl auristatin E, or MMAE, a type of chemotherapy drug called a microtubule inhibitor. Once the conjugate is taken up by cells, the drug stops them from dividing and leads to their death.

Because nectin-4 is present on the majority of bladder cancers, it’s not necessary to have a diagnostic test to determine which patients are eligible for treatment, explained Dr. Bellmunt.

The participants enrolled in EV-201 received infusions of the drug about 3 times a month until disease progression or unacceptable side effects occurred, or if they chose to leave the study for any reason.

The most common side effects included fatigue, hair loss, decreased appetite, changes in the ability to taste, and peripheral neuropathy. Febrile neutropenia—fever and a reduced number of white blood cells—was the most common serious side effect related to treatment.

Treatment-related rash also occurred in about half of participants but was usually mild.

Overall, side effects led 32% of patients to receive a lower dose of enfortumab vedotin and 12% to discontinue treatment. Peripheral neuropathy was the most common cause of dose reduction or treatment discontinuation.

At the time the trial’s preliminary results were published, almost half of the 55 patients who had had a response to the drug still hadn’t experienced progression of their cancer. Responses lasted from about 3 months to more than 11 months.

Though the trial is still ongoing, the researchers estimated that the median progression-free survival was 5.8 months, and the median overall survival was 11.7 months.

More to Study

Under an accelerated approval, a drug’s manufacturer must further study and verify a treatment’s clinical benefit. An ongoing phase 3 clinical trial is comparing enfortumab vedotin with taxane-based chemotherapy as third-line treatment.

There are currently unanswered questions about which third-line drug should be given first to people with FGFR-positive bladder cancer, who would also be eligible to receive erdafitinib.

“We don’t know if the order [of these drugs] matters. There’s no clinical trial or data [yet],” explained Dr. Bellmunt.

And because treatment response rates in the EV-201 trial were so high—comparable to what’s normally seen with first-line therapy—researchers are beginning to test enfortumab vedotin earlier in treatment, Dr. Zhang said.

For example, an ongoing trial is testing enfortumab vedotin alone and in combination with immunotherapy, chemotherapy, or both as an initial treatment for people with advanced bladder cancer.

Preliminary results from one arm of that trial were presented in September 2019 at the European Society for Medical Oncology’s annual meeting. That data showed response rates of around 70% with the combination of enfortumab vedotin and the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda) in patients who were too sick to receive platinum-based chemotherapy. Such a response rate is “phenomenal” for people with metastatic bladder cancer, explained Dr. Zhang.

“The concept is really to try to bring active treatments earlier in the disease process,” Dr. Zhang said. “We want to [learn] more about enfortumab vedotin, potentially even for [treating] localized disease.”