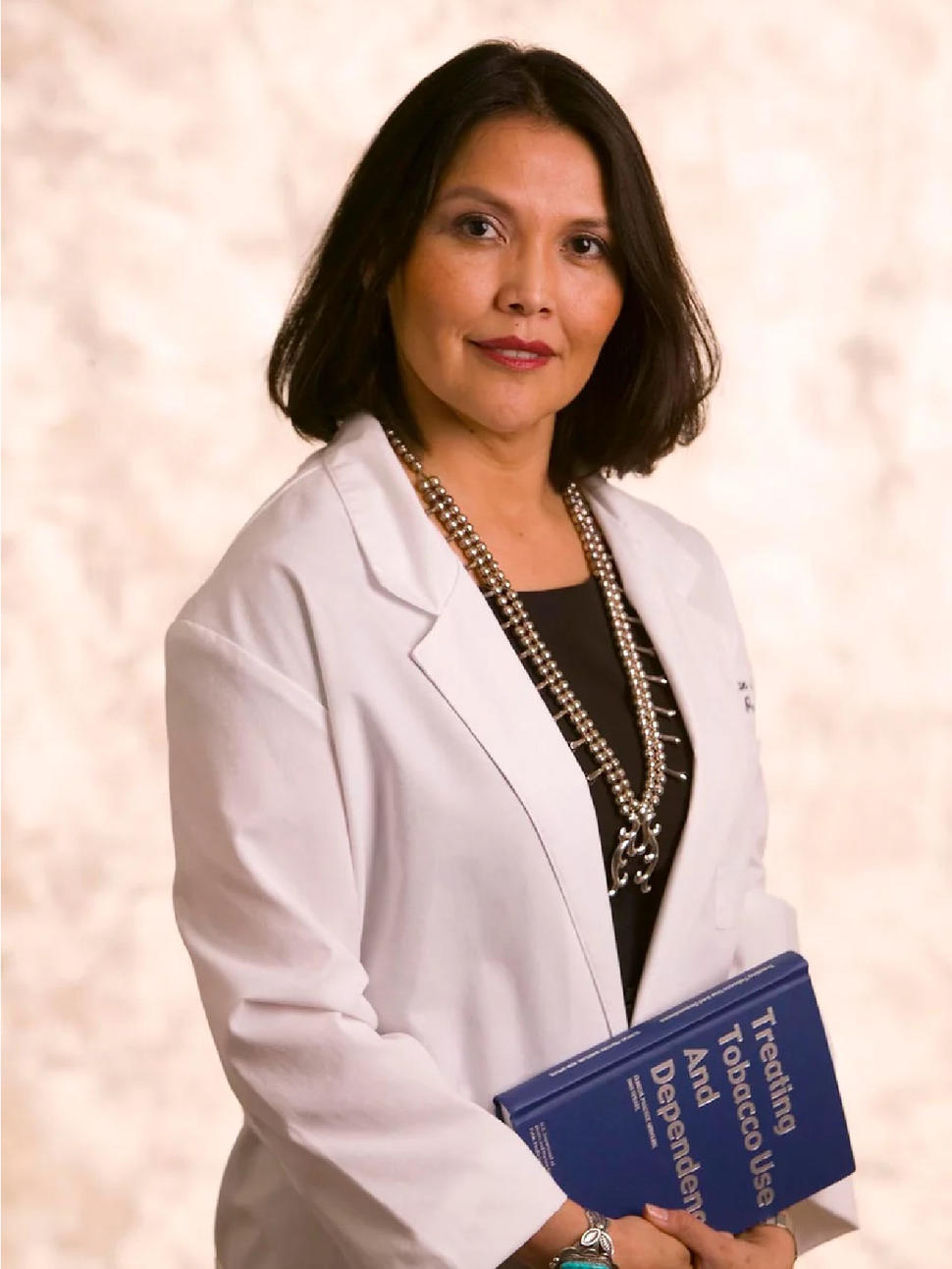

, by Patricia Nez Henderson, M.D., M.P.H., and Scott Leischow, Ph.D.

Dr. Nez Henderson of the Black Hills Center for American Indian Health is president-elect of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. Dr. Leischow is executive director of Clinical and Translational Science at Arizona State University’s College of Health Solutions.

In 2008, the first legislation introduced to the Navajo Nation Council calling for a ban on the use of all commercial tobacco products in all public buildings and businesses in the Navajo Nation proclaimed:

This past fall—following more than a decade of additional legislative proposals, research, collaboration, and outreach—the ban became a reality.

On November 6, 2021, the Navajo Nation enacted the Niłch’ Éí Bee Ííná – Air is Life Act of 2021, the first comprehensive ban on commercial tobacco products on American Indian tribal lands.

The prohibition—which went into effect on February 5, and includes casinos, other businesses, and public Navajo buildings and lands—covers conventional cigarettes, e-cigarettes, cigars, and similar products. It excludes tobacco used for ceremonial purposes and use of any tobacco product in a person’s home.

As researchers who have spent much of our careers documenting the health and economic burdens of commercial tobacco and ways to mitigate those burdens, it’s difficult to overstate what this ban means for the health of the Navajo people—the Diné, in Navajo—and its potential to inspire similar bans on other Indigenous lands.

The story of how this landmark achievement came to be is quite remarkable because, we can assure you, it wasn’t easy.

Tobacco: From Indigenous people to commercial exploitation

A good place to begin is with some history.

It’s important to understand how essential tobacco is to Navajo traditions and culture. A form of tobacco known as Dził Nat’oh is a centerpiece of traditional Navajo healing ceremonies. As one Navajo healer explained, Dził Nat’oh, “is not used … socially, without purpose. It’s only used to heal a person’s mind and body.”

The tobacco traditionally used by healers—which is grown and collected in its natural environment—is a very different, far purer product than the commercial tobacco that is grown on an industrial scale and then laced with chemicals to form more addictive and more lethal products.

Many people don’t know, in fact, that the word “tobacco” has Indigenous roots. Unfortunately, tobacco has also been an inseparable part of the colonization and exploitation that, over 6 centuries, has decimated many Indigenous communities.

In modern times, the impact of this exploitation is reflected in the high rates of commercial tobacco use among American Indian adults and youth. It’s also seen in the nearly inescapable exposure to secondhand smoke—a documented cause of lung and other cancers, as well as numerous other health problems—among the workers at the casinos in the Navajo Nation and other tribal lands.

Although there has been strong support for a ban on commercial tobacco products among the Navajo people—the largest American Indian tribe at around 400,000, or about 14% of the American Indian/Alaska Native population—a few key sticking points held up its advancement through the legislative process.

Among them were concerns that a ban would affect the use of tobacco for ceremonial purposes. But perhaps the most difficult hurdle to overcome was anxiety—fueled, in part, by tobacco industry propaganda—about the potential financial impact of commercial tobacco-free laws in Navajo Nation casinos.

Casinos generate revenue, and a lot of jobs, for the Navajo Nation (and other American Indian tribes), so it’s no surprise that worries about a ban hurting the casinos were front and center in this debate.

Research, outreach, advocacy

The initial failure to pass a ban on commercial tobacco in 2008 was followed by another failure and then another. Those of us involved in research and advocacy agreed that it was time to rethink our efforts.

That included revisiting the type of research that was needed to better understand the Navajo people’s relationships with ceremonial and commercial tobacco and their perceptions of commercial tobacco-free policies. A major source of that information came as a result of NCI funding of a large research project launched in 2011: Networks Among Tribal Organizations for Clean Air Policies (NATO CAP).

As might be expected, the research supported by NATO CAP was not white lab coats and pipettes kind of work.

Much of it involved talking with and collecting survey data from the Navajo community: healers, tribal elders, and other community leaders.

Those interactions and survey results tended to center around the intersection of traditional Navajo beliefs and commercial tobacco, and how that knowledge is exchanged in order to make decisions—an approach directly informed by NCI Tobacco Control Monograph 18, which described a systems-based approach to developing commercial tobacco control policies and practices.

Conducted over the course of several years, this research offered novel insights into how the Diné view and share information through their networks on commercial tobacco and commercial tobacco-free policies, including how such policies fit within traditional beliefs around clean air, harmony with the environment, and individual liberty.

It also provided a greater understanding of more pragmatic concerns about potential economic impacts on Navajo businesses and the health impacts of secondhand smoke on their employees.

With regard to these latter issues, we conducted investigations of how existing smokefree policies affected casinos. We found, for example, that a smokefree policy enacted in Illinois had no material economic impact on casinos there.

Working with other groups, we also gathered data on secondhand smoke in casinos. Those studies clearly showed that, even with modernized ventilation systems, exposure to particles from secondhand smoke was still dangerously high in the casinos.

Better data on commercial tobacco bans, strong advocacy, and a pandemic

What NATO CAP and other studies provided was a strong foundation that grassroots advocacy organizations, including a group called Team Navajo, could use to reinvigorate their efforts to get the commercial tobacco ban through the Tribal Council (the Navajo Nation equivalent of the US Congress).

Formed in the early 2000s, Team Navajo has been a regular presence in the Navajo Nation, serving as a conduit to educate the Navajo community about research on commercial tobacco, including the harmful effects of secondhand smoke, and to advocate for policies banning commercial tobacco.

In the late 2010s, equipped with stronger information and data, members of Team Navajo met with elders, legislators, and business leaders to educate them about the health benefits of a commercial tobacco ban and about the Navajo community’s support for such a ban. At the same time, they were able to allay concerns about any potential economic impact.

Advocacy efforts also involved widespread public education on these topics, often through radio, newspaper ads, and community meetings.

Ironically, it was the COVID-19 pandemic that provided the final opening needed to advance the ban in the legislature. One of the chief concerns about a ban was its implementation: How could it be rolled out in a way that would not be disruptive to businesses, particularly casinos?

But with casinos shuttered for an extended period during the pandemic, it became clear that the ban could be implemented while they were reopening—greatly minimizing what potentially could be an otherwise difficult transition to a commercial tobacco-free casino environment.

Translating research into practice, more tribes coming on board

Although most people probably don’t associate the idea of translational science with something like a commercial tobacco ban, this is an ideal example of it. Passing the ban required using knowledge gained from high-quality research and making that knowledge available to networks of elected leaders, advocates, and others. Ultimately, these efforts led to a change in policy that we know will save lives.

We also know that the impact of this policy change for the Navajo Nation has a potentially long wake. In December, for example, the Tribal Council of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina voted to ban smoking in the two casinos it runs on tribal lands (smoking can still be permitted in small, set-away areas).

Other tribes have enacted commercial tobacco bans that exclude their casinos, although there is clearly momentum toward including casinos in those bans.

Finally, as is the case with most achievements of this scope, it could never have happened without strong collaborations. That includes the collaborative research supported by NATO CAP. But it also includes the numerous local, regional, and national partners who helped push for this change—whether that was sending letters of support for a ban to the Tribal Council, providing economic data, or helping with legislative language.

Air is life. And thanks to the efforts of so many, we believe this ban will improve the lives of the proud people of the Navajo Nation.