Some cancers grow fast and spread quickly, while others grow so slowly that if they went undetected, the cancer would not result in any major problems.

Determining which cancers are aggressive or fast growing and will need immediate treatment is really important, but can often be challenging.

Prostate cancer in particular presents multiple diagnostic problems. Researchers around the world are working hard to try and improve testing for prostate cancer so that we can identify more of the aggressive cancers that need treating and reduce the number of harmless cancers that are diagnosed – known as overdiagnosis.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men in the UK, with around 52,300 new cases diagnosed every year, and increasingly sensitive tests mean that more prostate tumours are detected which are not life threatening, but it’s difficult to tell which tumours to treat immediately and which to monitor closely.

Now, research published in Nature Communications, has found that using an advanced MRI technique, to observe in real time the metabolism of tumours, may enable doctors to pinpoint these potentially aggressive or fast-growing cancers and guide treatment pathways.

The need for a targeted approach

Currently, there is no single definitive test for prostate cancer in the UK. Someone with suspected prostate cancer symptoms, or someone who has requested a prostate test, could be offered a PSA (prostate specific antigen) blood test, or a prostate gland examination by their GP. Depending on these results, they may be referred to a specialist, who will do a full assessment which may include an MRI scan and a biopsy if they are concerned. The results of the biopsy will grade the prostate cancer based on the Gleason scoring system.

What is the Gleason Score?

The Gleason Score is the most common system doctors use to grade prostate cancer. The grade of a cancer indicates how different the cells are compared to normal: the greater this difference, the more aggressive the tumour is likely to be. This gives your doctor an idea of how the cancer might behave and what treatment you need.

To find out the Gleason Score or Grade Group, a pathologist looks at several biopsies from your prostate.

The pathologist grades each sample of prostate cancer cells based on how quickly they are likely to grow or how aggressive the cells look.

While a standard MRI test has its merits, it lacks some of the detail to successfully differentiate between aggressive and non-aggressive prostate cancers, a problem that our researchers were keen to answer.

“Focussing this advanced MRI test on prostate cancer was critical because there are diagnostic challenges in this disease that require improvement from the current standard of care,” says Professor Ferdia Gallagher, joint senior author on the paper.

“The key challenge of standard MRI is differentiating what we call indolent prostate cancer from clinically significant disease. Indolent cancers usually require no active treatment and these patients are put onto active surveillance, which is used to monitor the disease over time, and avoids the side effects of radical treatment. Clinically significant disease requires treatment, and we want to detect it as early as possible.”

Being able to get more information about how prostate tumours will behave is really important because of the high numbers of people who are diagnosed with non-aggressive disease using the current standard of care work-up.

How does the new imaging work?

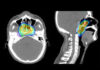

The emerging imaging technique, known as carbon-13 hyperpolarised imaging, works by measuring how quickly cells convert a naturally occurring molecule called pyruvate into another molecule called lactate.

This process produces energy and provides the building blocks for making new cells. Tumours have a higher metabolism to healthy cells, and so produce lactate more quickly.

The specialised scan has previously been used to see a detailed picture of breast cancer metabolism, which could show the cancer ‘breathing’ by imaging the tumours in real time. The same technique has also be used to monitor how well a patient is responding to chemotherapy within days of beginning treatment.

Previously, researchers have used this technique in trials of prostate cancer, where the scan was able to help doctors assess tumours by their overall pathological grade. This latest study however, jointly funded by us and Prostate Cancer UK, has allowed researchers to identify the tumours in even more detail, revealing subtle differences in tumours that can predict how they will behave.

Results from the study

Researchers used the specialised scan on 10 prostate cancer patients, whose tumours were subsequently removed and examined. The information on the aggressiveness of the prostate tumours taken from the metabolic MRI matched up to the findings from biopsy.

Using the innovative technique enabled researchers to identify several tumours that were not picked detected on standard MRI.

The scan was able to identify subtle differences in tumour aggressiveness within tumours of the same overall grade, which are important in determining whether a cancer requires immediate treatment.

As well as successfully recognising the difference between indolent and clinically significant disease, the scan was also able to tell the researchers about the metabolism in different compartments of the tumour itself, which may in the future allow clinicians to track response to drug treatments.

Ultimately, as well as improving the diagnostic performance of MRI and its specificity for aggressive disease, the new technique could also reduce the requirement for an invasive biopsy.

“Although this is a small study, it does show the potential of using hyperpolarised MRI to assess tumours in more detail. This technique could be critical when deciding to use “focal”, therapies, which involves treating the tumour rather than the whole prostate” says Gallagher.

“In the future this technique could help guide doctors with their treatment decisions, ensuring patients undergo immediate treatment if needed, or ensure their cancer is monitored closely when not on treatment”

What does this mean for patients?

Being able to save people from unnecessary treatment and its associated side effects could have a huge impact on quality of life for patients and their loved ones. Using MRI to make this decision rather than an invasive biopsy, presents an important potential advantage for patients as well as doctors.

The next step for the team is undertaking a multicenter trial, in collaboration with University College London, also funded by us. “This will allow us to build on these results in a larger setting and answer some of the questions about measuring response to therapy, but also having a larger group of samples will help us understand some of the underpinning biology of prostate cancer,” says Gallagher.

Scaling up the project will allow the team to see the potential for this innovative technology to become part of a routine MRI scan. “We hope that in 5, or maybe 10 year’s time, that this could be something that is more widely used in centres across the UK.”

Lilly