, by NCI Staff

Routine cervical cancer screening is very effective for preventing cervical cancer and deaths from the disease. On July 30, the American Cancer Society (ACS) published an updated guideline for cervical cancer screening. The guideline’s recommendations differ in a few ways from ACS’s prior recommendations and those of other groups. An expert on cervical cancer screening, Nicolas Wentzensen, M.D., Ph.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, explains the changes.

How have the cervical cancer screening recommendations changed?

The American Cancer Society’s new guideline has two major differences from previous guidelines. One is to start screening at a slightly older age, and the other is to preferentially recommend a type of screening test called an HPV test.

ACS recommends cervical cancer screening with an HPV test alone every 5 years for everyone with a cervix from age 25 until age 65. If HPV testing alone is not available, people can get screened with an HPV/Pap cotest every 5 years or a Pap test every 3 years.

These recommendations differ slightly from those given by ACS in 2012 and by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) in 2018.

| 2020 ACS | 2012 ACS | 2018 USPSTF | |

| Age 21‒24 | No screening | Pap test every 3 years | Pap test every 3 years |

| Age 25‒29 | HPV test every 5 years (preferred) HPV/Pap cotest every 5 years (acceptable) Pap test every 3 years (acceptable) |

Pap test every 3 years | Pap test every 3 years |

| Age 30‒65 | HPV test every 5 years (preferred) HPV/Pap cotest every 5 years (acceptable) Pap test every 3 years (acceptable) |

HPV/Pap cotest every 3 years (preferred) Pap test every 3 years (acceptable) |

Pap test every 3 years, HPV test every 5 years, or HPV/Pap cotest every 5 years |

| Age 65 and older | No screening if a series of prior tests were normal | No screening if a series of prior tests were normal | No screening if a series of prior tests were normal and not at high risk for cervical cancer |

What’s the difference between an HPV test, a Pap test, and an HPV/Pap cotest?

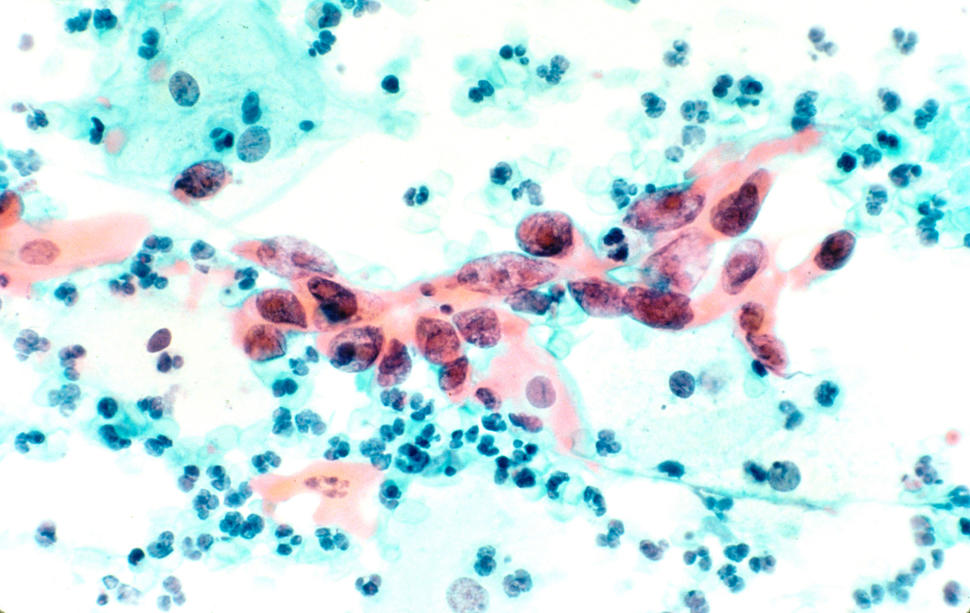

A Pap test, often called a Pap smear, looks for abnormal cells that can lead to cancer in the cervix. An HPV test looks for the human papillomavirus, a virus that can cause cervical cancer. For an HPV/Pap cotest, an HPV test and a Pap test are done together.

For a patient at the doctor’s office, an HPV test and a Pap test are done the same way—by collecting a sample of cervical cells with a scraper or brush.

The Pap test has been the mainstay of cervical cancer screening for decades. HPV tests are a newer method of cervical cancer screening. Two HPV tests have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use as a primary HPV test, meaning it is not part of an HPV/Pap cotest. Other HPV tests are approved as part of an HPV/Pap cotest.

Why does the new guideline recommend an HPV test over a Pap test or HPV/Pap cotest?

All three tests can find cervical cancer precursors before they become cancer. But studies have shown that HPV tests are more accurate and more reliable than Pap tests. Also, you can rule out disease really well with HPV tests so they don’t have to be repeated as frequently.

Although the Pap test has led to huge drops in rates of cervical cancer and death from the disease, it has some limitations. Pap tests have lower sensitivity compared with HPV tests, so they may miss some precancers and have to be repeated frequently. They also detect a range of abnormal cell changes, including some minor changes that are completely unrelated to HPV. So, many people who get an abnormal Pap test result actually have a very low chance of developing cervical cancer.

HPV/Pap cotesting is only slightly more sensitive than HPV testing, but it is less efficient because it requires two tests. And it detects a lot of minor changes that have a very low risk of turning into cancer. For an entire population, that’s a lot of additional effort and cost.

Screening with an HPV test alone was not recommended by ACS in 2012 because that approach wasn’t yet approved by FDA. The 2018 USPSTF guideline included HPV testing alone, cotesting, and Pap testing as equal options. The difference in the new ACS guidelines is that they elevate HPV testing alone over the other two tests.

Why does the new guideline recommend screening starting at age 25, instead of age 21?

Using information from new studies, ACS concluded that the benefits of cervical cancer screening do not outweigh the harms for people aged 21 to 24 years old.

This is an important change that is related to HPV vaccines. The first cohort of women who received the HPV vaccine when they were younger are now in their 20s and are eligible for cervical cancer screening. HPV vaccines are very good at preventing HPV infections, particularly infection with HPV types 16 and 18, the types that cause most cervical cancers. So, the vaccines have led to a drop in HPV infections and cervical precancer in this age group.

Also, in young women, most HPV infections go away on their own. Screening people in this age group often leads to unnecessary treatment, which can have side effects. That’s why ACS recommends starting screening at age 25.

Have the recommendations for those who are 65 years old or older changed?

No, the recommendations for this age group are the same as before. If you’ve had a series of normal screening test results over a long period of time, then you can stop screening at age 65. If, in the past, you had an abnormal result or anything suspicious on a screening test, or had treatment for cervical cancer or precancer, then you should continue to be screened.

The recommended age limit for cervical cancer screening has been consistent across different guidelines over the years. But there are current efforts to study the age limit more because it’s an area where we have less data. There is more interest now in looking at people who had an abnormal screening test result at an older age to see if they require more years of screening or more frequent screening.

If these screening tests save lives, isn’t it better for people to get tested more often and with more tests?

No. As with many tests, there is the potential to do more harm than good if they are applied too frequently. There are a few risks that come with cervical cancer screening tests.

Screening tests and follow-up tests can cause physical discomfort. There’s also the possibility of added anxiety and other emotions from incorrect, or false-positive, test results. And if you have an incorrect result, you may end up getting unnecessary follow-up tests or even unnecessary treatment.

Treatment for cervical cancer or precancer can permanently alter the cervix. That may raise the risk of serious complications in a future pregnancy, including pregnancy loss and preterm birth.

So, while testing more often or with more tests may seem like a good idea, it can actually lead to more harms. ACS carefully evaluated the potential benefits and harms of each screening test for each age group to come up with their updated recommendations.

Do people who got the HPV vaccine still need to get cervical cancer screening?

Yes, the new guideline recommends screening for those who have had the HPV vaccine. It does not recommend making a screening decision based on whether an individual has had the vaccine.

But, over time, as rates of HPV vaccination increase among people who are eligible for cervical cancer screening, we may see more changes in screening recommendations down the road.

Why do the guidelines for cervical cancer screening keep changing?

It’s a very dynamic situation, and that’s for multiple reasons. One is we have amazing results from the HPV vaccine, so that continually changes the picture for screening.

We also have seen great development of new technologies like HPV testing and improvement in some of the secondary tests that are used for following up after screening.

All these improvements have allowed us to make more accurate predictions of a person’s chances of getting cervical precancer and cancer. We also have new evidence from large studies that really give us the assurance that we can update screening practices to provide better outcomes for women and for the health care system.

What happens after someone gets an abnormal cervical screening test result?

If something abnormal or suspicious was found, also called a positive test result, you will typically get a second test. The standard approach is to do a Pap test, but there is also a new FDA-approved test, called dual stain. The dual stain test uses two biomarkers that can give a more accurate sign that precancer is present.

The results of the second test will help decide if you need a colposcopy—a procedure to look at the cervix with a magnifying lens and take samples from spots on the cervix that look abnormal.

ASCCP (formerly known as The American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology) recently published updated guidelines for the care of patients with abnormal cervical screening test results. This was a large consensus effort involving several clinical organizations, federal agencies, and patient representatives. Several NCI scientists, including myself, performed extensive risk assessment and systematic literature reviews to support the development of the guidelines.

Using all the information that we have on the risk of cervical cancer and precancer, the guidelines create a framework that helps doctors make decisions about follow-up care based on a patient’s total risk level.

The 2012 ASCCP guidelines were based on which test a patient got and what the results were. The new recommendations are more precise and tailored to many factors that determine a person’s risk of cervical cancer and precancer, such as their age and past test results.

Now, doctors can use any combination of test results to determine an individual’s risk and decide whether that person should, for example, get a colposcopy or come back in a year to repeat the screening test.