June 5, 2018, by NCI Staff

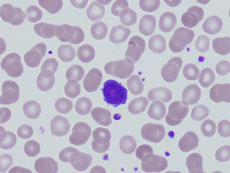

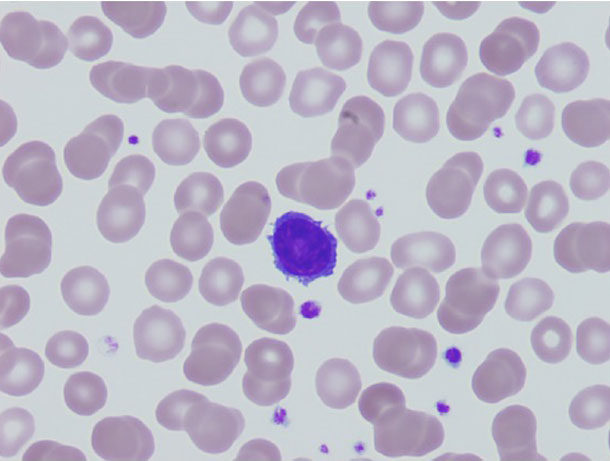

A peripheral blood smear showing several hairy leukemia cells.

Credit: Case Rep Pathol July 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/497027. CC BY 3.0.

People diagnosed with hairy cell leukemia (HCL), an uncommon form of leukemia, may soon have an effective new treatment option, according to findings from an international phase 3 clinical trial. In the trial, three-quarters of people with HCL that had come back or progressed after earlier treatment responded to treatment with the toxin-based drug moxetumomab pasudotox (Moxe).

The disease disappeared completely during treatment in 33 of the 80 patients (41%), and more than 70% of these patients remained cancer free after 6 months of follow-up. The trial results were presented June 2 at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting in Chicago.

“This drug offers an option for patients with relapsed or refractory hairy cell leukemia that avoids additional chemotherapy and also has the potential to provide better long-term outcomes,” said Robert Kreitman, M.D., of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research (CCR), who led the trial.

Bringing a Toxin to Its Target

Moxe is a type of drug called an immunotoxin. It consists of a fragment of a toxin naturally made by the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which is genetically fused to a carrier molecule. This carrier molecule, a portion of a monoclonal antibody, recognizes a protein called CD22, which is found in abundance on HCL cells. When the antibody locates and binds to a cell bearing CD22, the toxin is taken inside the cell and kills it.

Moxe was initially developed in CCR’s Laboratory of Molecular Biology, by a team led by Ira Pastan, M.D., and that included David FitzGerald, Ph.D., also of CCR. The drug was later licensed for commercial development to MedImmune, a subsidiary of AstraZeneca.

In a phase 1 trial, which enrolled 49 people with relapsed or refractory HCL, Moxe had shown promising safety and potential for effectiveness. Of the 33 participants who received the highest dose of the drug, more than 60% had a complete response (the disappearance of all signs of cancer by established tests) that lasted more than 3 years on average.

Based on these results, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) allowed the researchers to go straight from the phase 1 trial to the international phase 3 trial, which was sponsored by MedImmune.

Eliminating the Repository of Resistance

Because there are no drugs approved by FDA for the treatment of relapsed or refractory HCL, the phase 3 trial was a single-arm study, in which all participants received Moxe.

The trial included 80 participants from 14 countries, who had received an average of three previous treatments for their HCL. During the trial, participants could receive up to six cycles of the drug over a 6-month period.

Repeated cycles of treatment with Moxe can eliminate minimal residual disease, explained Dr. Kreitman. Minimal residual disease refers to tiny deposits of cancer cells that can hide deep within the bone marrow and avoid being killed by standard chemotherapies.

“Minimal residual disease is what we think causes HCL to relapse and is the reason this disease keeps coming back over and over again,” he said. “We feel that the long-term results for HCL patients will be better if we can get rid of the minimal residual disease.”

Treatment was stopped early, however, in trial participants who had a complete remission without evidence of minimal residual disease before receiving the full 6 cycles.

After almost 17 months of follow-up, 80% of trial participants had a hematologic remission—that is, normal blood cells returned to acceptable levels. More than 40% of patients experienced a complete response with Moxe treatment, the researchers reported, most of whom had no evidence of minimal residual disease.

Side effects from the drug were mostly mild. They included nausea, swelling in the hands and feet, headache, and fever. Importantly, Dr. Kreitman said, the researchers did not see any cumulative toxicity in patients. Cumulative toxicity is when side effects get worse the longer a treatment goes on.

“That’s important because we want to get rid of minimal residual disease, and that can happen if patients are given enough treatment cycles,” he explained.

Unlike chemotherapy drugs used to treat HCL, Moxe did not cause any permanent damage to the stem cells in the bone marrow, which produce red and white blood cells.

Next Directions for Moxe

Because HCL cells express a very large amount of CD22 on their surface, in theory, all patients could experience a complete remission with Moxe, explained Dr. Kreitman. However, multiple factors can affect whether an individual patient benefits from the drug.

For example, people who have been exposed to P. aeruginosa before being diagnosed with HCL would have developed antibodies to it and the toxins it can produce. These antibodies could recognize Moxe and inactivate it before it reaches enough HCL cells, Dr. Kreitman said.

This would not be the only reason for treatment resistance, though. During the trial, the researchers tested participants for antibodies to Moxe, and many patients with antibodies still had a good response to the drug, particularly if antibody levels were low, Dr. Kreitman said. He and others in Dr. Pastan’s laboratory are trying to better understand why some patients with HCL don’t respond to the drug.

Others are testing the drug in other types of leukemia. Moxe was recently tested in a clinical trial that enrolled children with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Although resistance to the drug developed quickly, studies are looking at ways to combine Moxe with other drugs to overcome this resistance.

Using Moxe earlier in the treatment of HCL could also potentially be beneficial, said Dr. Pastan.

“The dream now is to not use drugs that are toxic to patients’ bone marrow, like cladribine, which is currently used as a first-line therapy for hairy cell leukemia,” he said.