December 7, 2018, by NCI Staff

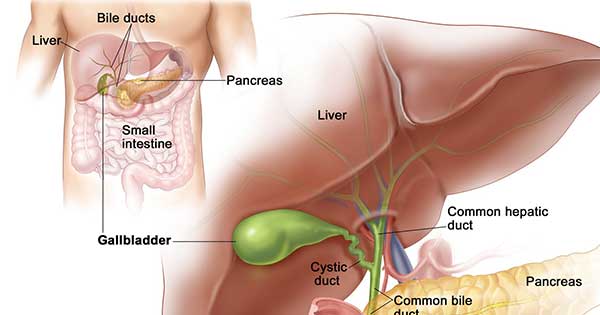

In patients with biliary tract cancer, a combination of two targeted drugs can shrink tumors with a specific genetic mutation.

Credit: National Cancer Institute

In an early-phase clinical trial, a drug combination that targets tumors with a specific genetic mutation improved outcomes for patients with rare gastrointestinal (GI) cancers that have the mutation.

The combination, dabrafenib (Tafinlar) plus trametinib (Mekinist), shrank tumors in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer and adenocarcinoma of the small intestine. There are few effective treatments for either type of cancer, and long-term survival is poor, particularly for patients with biliary tract cancer.

The 36 patients in the trial all had a specific genetic mutation in the BRAF gene, called BRAF V600E. The mutation is found in about 15% of biliary tract cancers and adenocarcinomas of the small intestine, said one of the trial’s lead investigators, Zev Wainberg, M.D., of the gastrointestinal oncology program at UCLA.

Dabrafenib blocks the BRAF protein, and trametinib inhibits MEK, a molecule that is in the same cell signaling pathway as BRAF. The drugs are already being used together in the clinic, having been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to be used in combination to treat patients with melanoma, anaplastic thyroid cancer, and non-small cell lung cancer whose tumors have the BRAF V600E mutation.

The trial findings were presented November 16 at a symposium on molecular targets and cancer therapeutics sponsored by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, NCI, and the American Association for Cancer Research. The findings have not yet been published.

Given that patients diagnosed with biliary tract cancer have “very poor prognoses” and limited therapeutic options, Dr. Wainberg said, “the results are very compelling.”

Promising Findings for Biliary Tract Cancer

Currently, the first-line therapy for biliary tract cancer is a combination of the chemotherapy drugs cisplatin and gemcitabine. There is no standard therapy for patients whose cancers progress after initial treatment, with most second-line therapies typically showing little if any efficacy.

This international phase 2 trial, called ROAR, is not focused on a specific cancer type. Rather, it is “a basket trial,” Dr. Wainberg explained, that includes nine rare tumor types in which all patients have the same molecular alteration.

The trial enrolled patients whose disease had already progressed on standard treatments. At the symposium, he reported that 13 of the 32 evaluable patients with biliary tract cancer and 2 of the 3 patients with adenocarcinoma of the small intestine had experienced enough reduction in the size of their tumors to be classified as a tumor response.

Patients with advanced or metastatic biliary tract cancer like those enrolled in the trial would normally be expected to survive a few more months. But those in the trial survived a median of 12 months.

The most common side effects experienced by patients in the trial were fatigue, low-grade fevers, and blood count changes, he reported.

An Increasing Number of Potential Molecular Targets for Biliary Tract Cancer

The trial involved researchers from universities, medical institutions, and pharmaceutical companies in eight countries in Europe as well as the United States. The trial was designed to expedite the FDA approval process, even though relatively small numbers of patients could be enrolled for these rare tumors with BRAF mutations, Dr. Wainberg said. The goal was to show efficacy with relatively small groups of patients, he noted, with toxicity across the entire group taken into account.

“The response rate they describe is certainly very encouraging,” commented Tim Greten, M.D., head of the gastrointestinal malignancy section of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research. He noted that other genetic features found in some cases of biliary tract cancer—mutations in the IDH1 and IDH2 genes and FGFR fusion gene—are also under investigation as potential molecular targets for treatment, with ongoing clinical trials at various stages.

“This study adds to our knowledge and reinforces that patients with biliary tract cancers should have their tumors sequenced or analyzed for molecular changes,” Dr. Greten said. “This work adds a molecular change that we may be able to target therapeutically.”

Drs. Wainberg and Greten hesitated to speak conclusively about the findings on adenocarcinoma of the small intestine given the very small number of patients with that cancer who were enrolled in the study. Dr. Wainberg said the trial attempted to recruit at least 10 patients for each type of rare cancer studied, but the investigators were only able to enroll three with small intestine cancer.

Targeting BRAF across Cancer Types

The BRAF V600E mutation leads to the substitution of one amino acid for another in the BRAF protein. This change causes the protein to become hyperactive, directing excessive signaling through MEK and other proteins and causing unregulated cell growth. The V600E mutation accounts for 90% of the BRAF mutations found in cancer cells.

Past research, especially in melanoma, showed that inhibiting MEK and altered BRAF simultaneously is more effective than inhibiting either alone.

“For a number of cancer types, the combination has already proven to be better than the single-agent BRAF inhibitor,” Dr. Wainberg said. Using combination therapy can also help prevent tumors from developing drug resistance, he added.

Promising results have been obtained for four of the nine patient groups (cohorts) in the trial, he noted. FDA’s approval of the dabrafenib–trametinib drug combination to treat anaplastic thyroid cancer was based on results from this trial. The group also presented promising results with this combination for the treatment of hairy cell leukemia at the American Society of Hematology meeting in early December. (See the box below.)

“What I hope comes out of these findings, and what I think is supported by the data, is that patients at any point can be checked to see whether they have the BRAF mutation,” Dr. Wainberg said. “If they do, consideration should be given to using these drugs.”