, by NCI Staff

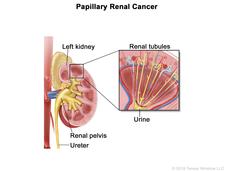

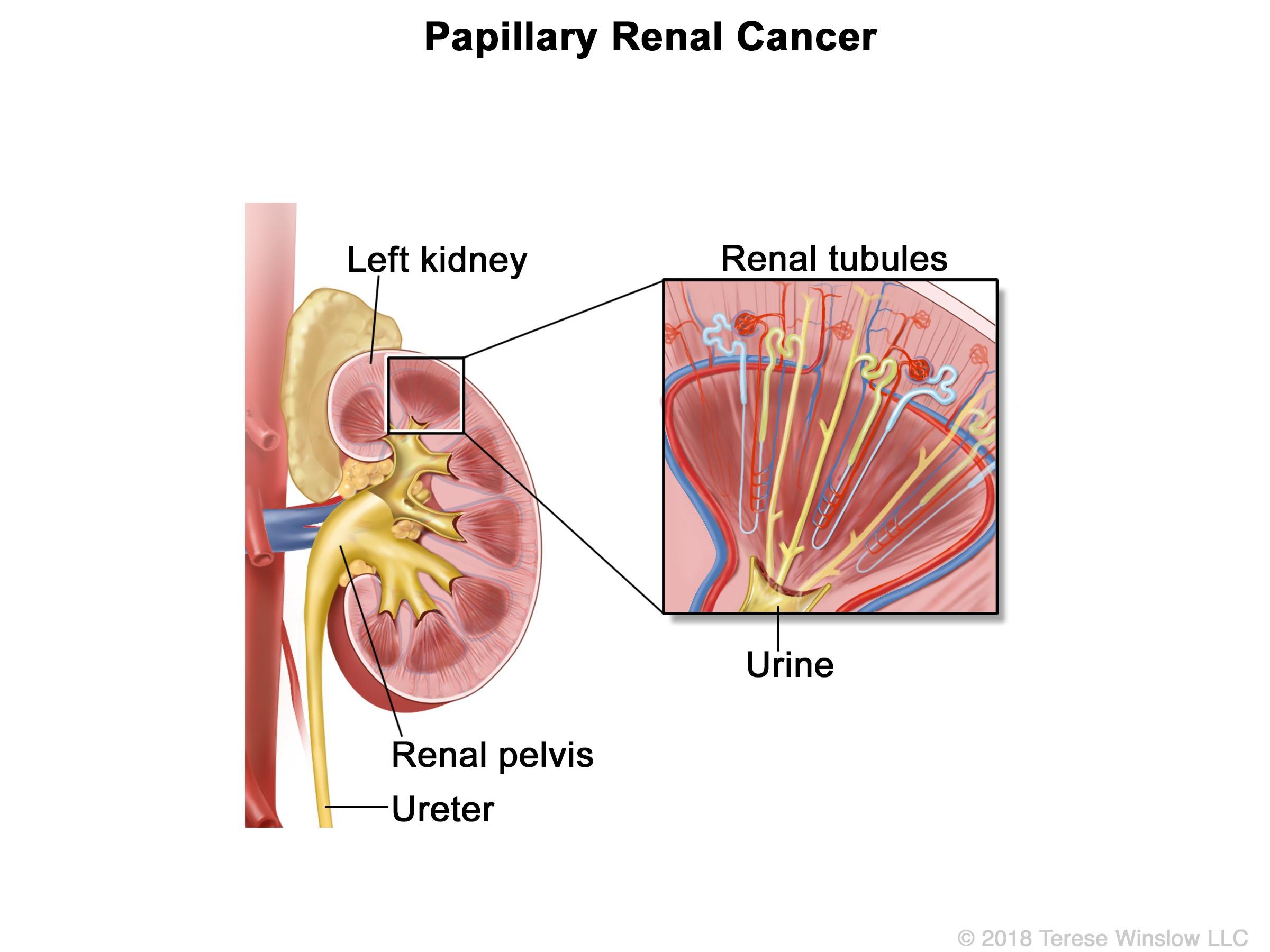

Results from a new study have identified the most effective treatment option to date for some people with papillary renal cell carcinoma (PRCC), a rare type of kidney cancer.

In the first-ever completed randomized clinical trial for people with PRCC that has spread elsewhere in the body (metastasized), patients who received the targeted drug cabozantinib (Cabometyx) as their first treatment lived for a median of 9 months without their disease getting worse.

In contrast, people who received sunitinib (Sutent), another targeted therapy, lived for about 5 and a half months without their disease progressing. Two other drugs tested early in the trial—crizotinib (Xalkori) and the experimental drug savolitinib—were not any better than sunitinib at slowing or stopping the cancer’s growth.

Results from the NCI-sponsored trial, called SWOG S1500, were presented on February 13 at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Genitourinary Cancers Symposium and published in The Lancet.

Since tumors in people with metastatic PRCC will eventually progress on any currently available therapy, patients will likely get more than one targeted drug during treatment, explained Stephanie Berg, D.O., of Loyola University Medical Center, who was not involved with the study. But the results from the trial indicate that for now, “you’re going to get the most ‘bang for your buck’ from cabozantinib” for the initial treatment of metastatic PRCC, Dr. Berg said.

PRCC is not only a rare disease, but a complicated one, said Ramaprasad Srinivasan, M.D., Ph.D., of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research, who also was not part of the study. Although it’s given a single name, it’s really a collection of diseases with different genetic alterations, he added.

Studies have begun to uncover the wide range of these causes, hopefully paving the way for more individualized approaches to treatment, Dr. Srinivasan explained. By tailoring treatment based on the molecular changes driving each person’s cancer, he’s hopeful that in the future, “we should be able to do better than 9 months of progression-free survival,” he said.

A Rare Set of Diseases

Most kidney cancers are a type called clear cell. Beginning in the 1990s, scientists at NCI and elsewhere uncovered many of the genetic changes that can drive the development of clear-cell kidney cancers. Targeted therapies that can block the effects of those changes quickly followed.

But about 15% of people diagnosed with kidney cancer have PRCC, which starts in a different type of kidney cell. Until recently, the molecular basis of PRCC wasn’t understood.

However, recent data from The Cancer Genome Atlas and other research efforts highlighted that some cases of PRCC are driven by changes in a gene called MET. The resulting abnormal MET protein can potentially be shut down by several existing drugs.

Sunitinib, which was one of the first targeted therapies to prove effective against clear-cell kidney cancer, has also been used to treat PRCC. However, sunitinib shrinks tumors—or stops them from growing—in less than a quarter of people with PRCC, explained Sumanta Pal, M.D., of the City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, who led the SWOG trial.

And to date, due to the rarity of PRCC, no randomized study testing other drugs against each other has been completed, he explained at the ASCO meeting.

The SWOG team designed the S1500 trial to compare several drugs that block MET with sunitinib in patients with metastatic PRCC.

Cabozantinib targets MET, but also does double-duty by blocking a different protein called VEGF that tumors use to hijack the body’s blood supply. Both crizotinib and savolitinib target MET but not VEGF. Sunitinib blocks VEGF but does not target MET.

Narrowing Down Potential Treatments

The SWOG S1500 trial was led by the SWOG Cancer Research Network and conducted through NCI’s National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN), which is overseen by NCI’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP).

Over almost 4 years, researchers at 65 treatment centers in the United States and Canada enrolled 147 people with metastatic PRCC in the randomized phase 2 trial. At the start of the trial, the research team randomly assigned people to receive either sunitinib or one of three MET inhibitors: cabozantinib, crizotinib, or savolitinib.

A planned early analysis of the results found that neither crizotinib nor savolitinib was better than sunitinib at extending the time people lived without their disease progressing, and those drugs were dropped from the trial. From that point forward, new participants received either cabozantinib or sunitinib.

In the cabozantinib group, 23% of participants had their tumors shrink during treatment, compared with 4% of those receiving sunitinib. Two out of 44 people receiving cabozantinib (5%) had their tumors disappear entirely during treatment, known as a complete response. No complete responses were seen in patients treated with any of the other drugs.

At the time of the final analysis, people who received cabozantinib lived a median of 9 months without their disease progressing, compared with 5.6 months for sunitinib. Because people in the trial could receive further treatment once their tumors stopped responding to any of the study drugs, it wasn’t possible to tell if there was a difference in how long people lived overall between those who received cabozantinib or sunitinib, Dr. Pal reported at the meeting.

Most patients treated with either drug experienced at least one serious side effect, with high blood pressure being the most common for both. About a quarter of people in both groups stopped treatment due to side effects. One person in the cabozantinib group died of a blood clot within 30 days of their last medication dose.

More Personalization Needed

Currently, no drugs are approved by the Food and Drug Administration specifically for PRCC, Dr. Srinivasan explained. Given the dearth of effective options, cabozantinib is already being widely used for this rare cancer, “but this data formalizes and lends more support for that practice,” he said.

Understanding the wide range of genetic changes that drive PRCC will be vital for designing more personalized combinations of drugs—including targeted drugs and immunotherapies—going forward, he added.

For example, his team recently found that people with one known subtype of hereditary PRCC had strong responses to treatment with the drugs bevacizumab (Avastin) and erlotinib (Tarceva), which target changes specific to that subtype. In that small clinical trial, those patients lived a median of almost 2 years without their disease progressing.

And while the S1500 trial tested three MET inhibitors, the researchers weren’t able to test whether everyone participating actually had tumors that were driven by MET. Using molecular testing to select patients for treatment might have resulted in better results from the MET inhibitors, they wrote in The Lancet.

Scientists who study PRCC were especially surprised that savolitinib—which is a strong MET inhibitor—wasn’t effective in this trial or another trial that was stopped early in 2019, Dr. Berg explained. Researchers are planning on exploring whether patients whose tumors have other molecular markers would benefit from savolitinib, she said.

“Such examples are why I think biomarker testing is going to have a big role as we move forward with these kinds of studies [in PRCC],” said Dr. Srinivasan. “We’re not there yet, but I think that’s the direction in which we should be heading.”

For now, given the disease’s rarity, he recommends that people newly diagnosed with the disease get a referral to work with a kidney cancer specialist whenever possible.

“When you’re dealing with a rare form of cancer, you need an expert,” he said. “People need someone [who can have a discussion] about the various treatment options that are out there, and what might be best for them.”