, by NCI Staff

When cancer spreads to the bone, it can cause pain, fractures, and other problems. Clinical guidelines recommend that patients whose cancer has spread to their bones receive regular infusions of a bone-modifying drug, such as zoledronic acid (Zometa), to help manage these complications.

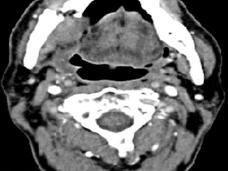

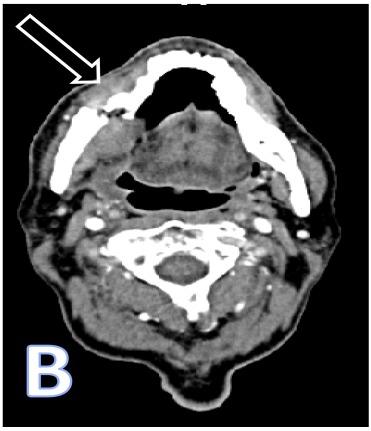

But such drugs can have harmful side effects, including osteonecrosis of the jaw, a rare but potentially debilitating condition in which bone tissue in the jaw is no longer covered by the gums and starts to die.

Until now, doctors didn’t have a clear idea of how often people with cancer taking zoledronic acid developed this condition, with previous estimates ranging from 1% to 15%.

Now, a study of nearly 3,500 people has provided more definitive risk estimates. The risk of zoledronic acid causing osteonecrosis of the jaw in people with cancer in their bones, the study found, is about 1% after a year of being on the drug, 2% after 2 years, and 3% after 3 years.

The NCI-funded study, run by the SWOG Cancer Research Network, also found that poor dental health and smoking were risk factors for developing osteonecrosis of the jaw in these patients.

The study results, published December 17 in JAMA Oncology, also showed that people who received the same dose of zoledronic acid more frequently had a greater risk of developing osteonecrosis of the jaw.

“This is one of the first studies to systematically evaluate dental health and the risk for developing osteonecrosis of the jaw with zoledronic acid,” said Lori Minasian, M.D., deputy director of NCI’s Division of Cancer Prevention, who helped facilitate the study but was not a study investigator. “It goes a long way in helping us understand the harms of zoledronic acid and related drugs and will help us use the drugs better” when treating people with cancer, Dr. Minasian said.

For instance, doctors may consider giving zoledronic acid at less frequent intervals, said Charles Loprinzi, M.D., of the Mayo Clinic, who was not involved with the study. He noted that previous studies have shown that giving zoledronic acid every 12 weeks is as effective in preventing complications of bone metastases as giving the drug every 4 weeks.

And patients can also play a role in reducing the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw, Dr. Minasian said.

“If there’s a message to cancer patients, it’s to take care of your teeth—brush your teeth, go to your dentist, and make sure that your oral health is in good shape,” she said.

A Link between Poor Dental Health and Risk of Osteonecrosis of the Jaw

Zoledronic acid and similar drugs, known as bisphosphonates, interfere with the breakdown of bone tissue that results when cancer cells grow in the bone. But these drugs also interfere with the normal process of breakdown and rebuilding that keeps our bones healthy, Dr. Loprinzi said.

In 2003, oral surgeons first noticed that some patients receiving bisphosphonates were developing osteonecrosis of the jaw—a condition rarely seen before then. The mechanisms by which bisphosphonates cause this condition are not known and it is hard to treat.

To assess the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw in people with cancer, the SWOG study team, which included dental specialists as well as cancer researchers, enrolled 3,491 patients who were planning to receive zoledronic acid for metastatic bone cancer. The most common cancer types among study participants were breast, prostate, and lung cancer and multiple myeloma, a cancer that starts in the bone.

Participants were monitored every 6 months and followed for up to 3 years. A baseline dental checkup was done in 2,263 participants, and patients were recommended to get dental checkups every 6 months.

After 3 years, about 2.8% of patients (90 people) had confirmed osteonecrosis of the jaw, which was defined as having an area of exposed bone in the jaw that had been present for at least 8 weeks.

“At the end of 3 years, we found that if you had started by having poor dental health—missing teeth, dentures, or prior oral surgery, as well as if you were a smoker, you were more likely to develop this complication,” said study investigator Julie Gralow, M.D., of the University of Washington School of Medicine.

Current smokers were about twice as likely to develop osteonecrosis of the jaw as former or never smokers. In addition, patients who received more total doses of zoledronic acid within the first year of treatment (or longer) were more likely to develop osteonecrosis of the jaw than those who received fewer doses.

While the overall rate of osteonecrosis of the jaw was approximately 3% at 3 years, it varied somewhat by cancer type. The rate was highest, for instance, in people with multiple myeloma (4.3%) and lowest in those with breast cancer that had metastasized to the bone (2.4%). Patients with multiple myeloma are likely to receive zoledronic acid at more frequent intervals than patients with breast cancer, Dr. Gralow noted.

Not surprisingly, the development of osteonecrosis of the jaw caused significant problems for patients. They reported “more pain, interference with eating and speech, and worse oral health-related quality of life,” the study investigators wrote.

Over the course of the study, some people also received a different type of drug that interferes with bone breakdown, denosumab (Xgeva), which became available after the study began.

“We were hopeful that denosumab would not be associated with a risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw,” Dr. Gralow said. However, subsequent studies have shown development of osteonecrosis of the jaw during treatment with denosumab, at rates comparable to those seen with zoledronic acid, she said.

Useful Information for Doctors and Patients

This study “provides information that physicians can use when talking to their patients,” Dr. Gralow said. “When we talk about the benefits and harms of giving zoledronic acid, we now have more accurate numbers. And we can also better talk about who might be at higher risk, such as smokers or patients who have dental problems … and can [then take steps] to reduce the risk of side effects,” she continued.

Ultimately, Dr. Gralow said, researchers hope to develop better ways to treat osteonecrosis of the jaw as well as to prevent it.

Some key questions that remain are: How often, and how long, should patients with bone metastases be given zoledronic acid?

Although some experts have suggested that people get the drug for 2 years and then stop, “there is no universal agreement on this because no one has done a definitive study,” Dr. Loprinzi said.

In addition, the study did not provide data on whether the risk of developing osteonecrosis of the jaw continues to rise after more than 3 years on zoledronic acid, said study leader Catherine Van Poznak, M.D., of the University of Michigan in an interview for JAMA Oncology. However, Dr. Poznak expressed concern that the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw will indeed continue to increase with time.