May 23, 2018, by NCI Staff

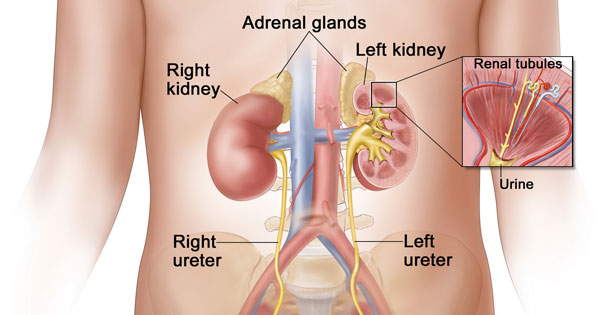

Wilms tumor is the most common type of kidney cancer in children, and accounts for about 5% of all childhood cancers.

Credit: National Cancer Institute

Results from an NCI-sponsored clinical trial suggest that some children with advanced Wilms tumor, a form of kidney cancer, may be able to skip radiation therapy.

The findings from the trial, led by the Children’s Oncology Group (COG), suggest that nearly half of children whose cancer has spread to their lungs can be spared lung radiation therapy without harming their long-term survival. This treatment approach, the study leaders believe, could greatly reduce the risk of some of the common and potentially fatal late effects of radiation therapy, including breast cancer, heart failure, and lung scarring.

The study results were published April 16 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Wilms tumor, the most common type of kidney cancer in children, accounts for about 5% of all childhood cancers, with approximately 650 cases diagnosed in the United States each year. About 10% of Wilms tumor cases are diagnosed as stage IV, where the cancer has spread beyond the kidney, most commonly to the lungs.

Treatment with the combination of surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy has increased 5-year survival rates for children with all stages of Wilms tumor from 40% in the 1950s to nearly 90% today.

“In a way, it’s a luxury that we’ve had such good outcomes with Wilms tumor and, in some cases, can pull back on therapy,” said Nita Seibel, M.D., head of Pediatric Solid Tumor Therapeutics in NCI’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, who helped design and launch the COG study before joining NCI.

“We’re at the point where we want to optimize quality of life, in addition to optimizing survival,” Dr. Seibel continued. “The ultimate goal for these patients is that their quality of life be very similar to someone who never had Wilms tumor.”

Customizing Therapy for Patients with Lung Metastases

When the COG study began in 2007, the standard treatment for patients with stage IV Wilms tumor was chemotherapy and surgery, followed by radiation therapy to the lungs, explained David Dix, M.B., a pediatric oncologist at the British Columbia Children’s Hospital, who led the study.

But results published in 2011 from a clinical trial conducted in Germany showed that Wilms tumor patients whose lung metastases shrank quickly in response to chemotherapy tended to have better outcomes. Those whose lung metastases persisted or grew during initial chemotherapy were at greater risk of dying within 5 years.

“Our approach [in the COG study] was to try to maintain excellent outcomes but de-escalate therapy in a proportion of patients,” Dr. Dix said.

In the nearly 300-patient study, children whose lung lesions were no longer visible on computed tomography (CT) scans after 6 weeks of standard chemotherapy continued treatment with standard chemotherapy only. Patients who still had visible lung lesions after 6 weeks continued standard chemotherapy and also received radiation therapy and two additional drugs, a chemotherapy treatment the researchers called Regimen M.

Both groups of patients had high 4-year survival rates: 96.1% in the chemotherapy-alone group and 95.4% in the group treated with radiation and more intensive chemotherapy. The 4-year rate of event-free survival—defined as lack of cancer recurrence, progression, or death—was 79.5% in the chemotherapy-alone group and 88.5% in the more intensive treatment group.

The worse event-free survival in the chemotherapy-alone group illustrates the difficulty of trying to balance avoiding the late effects of treatment while still achieving excellent long-term survival, Dr. Seibel explained. Although many patients were spared radiation to their lungs and the late effects that can come from that, a small group who had an event then had to get additional chemotherapy and radiation to be cured.

“A challenge that remains is to identify those patients who, at diagnosis, need to get more therapy, including radiation, and those who do not,” she said.

The COG researchers compared the results from their trial with those seen in an earlier clinical trial, called NWTS-5, that used the standard treatment for all patients with stage IV Wilms tumor with lung metastases: surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy to the lungs.

Overall, the 4-year survival rate was 84.0% in the NWTS-5 study and 95.6% in the COG study. The 4-year event-free survival rate was 72.5% in NWTS-5 and 85.4% in the COG study.

The findings suggest that the treatment strategy used in the COG trial substantially improves overall survival and event-free survival. But Andrew Davidoff, M.D., the chair of the surgery department at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, cautioned that the patients in the NWTS-5 and COG trials are not the same. Patients in both trials were supposed to have cancer that had spread to their lungs. But Dr. Davidoff noted that in the COG trial lung lesions were diagnosed only by CT scans rather than chest x-rays and biopsies.

CT scans detect more lesions than chest x-rays, including some that aren’t actually cancer. “A number of studies have shown that many lung nodules seen on CT scans aren’t Wilms tumor,” Dr. Davidoff said.

That’s worrying, he continued, because some patients received more intensive therapy because their lung lesions didn’t disappear, even though the lesions weren’t confirmed to have cancer cells. In fact, in the small subset of patients in the COG study who underwent biopsy of their lung lesions after 6 weeks of chemotherapy, the majority of the lesions biopsied were found not to have cancer cells.

“We strongly recommended that lung lesions be biopsied,” Dr. Dix said, but “the decision to biopsy was determined by treating physicians, and few doctors did.”

Dr. Dix pointed out, however, that the patients who had biopsies aren’t necessarily representative of the overall trial group. Doctors were more likely to take biopsy samples of lesions that were more accessible and generally resisted subjecting children to many invasive procedures, he explained.

It is also worth noting, Dr. Davidoff cautioned, that children whose lung lesions disappeared after 6 weeks of chemotherapy had lower rates of event-free survival in the COG study than in NWTS-5 (79.5% versus 85%). The difference was almost statistically significant.

Still, he said, an increase in the rate of relapse may be an acceptable trade-off because overall survival rates were high. “And you’ve spared a number of patients the complications associated with radiation therapy,” Dr. Davidoff said.

Optimizing Both Survival and Quality of Life

The more intensive treatment with Regimen M has potential risks, Dr. Seibel said. Previous research suggests that one of the additional drugs, cyclophosphamide, increases the risk of infertility , lung scarring, and other cancers, especially when used in combination with radiation therapy. The second added drug, etoposide, appears to increase the risk of developing a form of leukemia that is difficult to treat.

Dr. Seibel agrees with the concern that some patients may have been overtreated.

“It’s good that there’s a group of patients for whom we can decrease treatment, but we need to better define the group that needs more intensive therapy,” she said.

Because so many of the few lung biopsies in the trial were found to be benign, suggesting that some patients were overtreated, COG researchers strongly encourage lung biopsies for patients at the outset of treatment. While doctors understandably don’t want to subject children to more procedures than necessary, minimally invasive procedures can now often be used to perform lung biopsies, Dr. Seibel said.

Overall, Dr. Dix said, “These results are really encouraging. This approach definitely needs finessing, but it has taught us a huge amount.” Although this study used response to chemotherapy after 6 weeks to tailor treatment strategies, Dr. Dix said, “there’s no doubt that, in the future, the tools to stratify patients will rely more on genetic markers.”