Scientists have discovered that cells from different parts of kidney tumours behave differently and those in the centre are the most dangerous – in a “critical” step towards understanding how to target cancer spread.

Cancer can move from one part of the body to another to form secondary tumours. Known as metastasis, this spreading makes the disease much harder to treat.

Now a new study by researchers from the Francis Crick Institute, Royal Marsden, UCL and Cruces University Hospital, funded in part by Cancer Research UK and published in Nature Ecology and Evolution, has unearthed fresh information about cancer migration that could lead to new treatments.

“These findings are a critical foundation for considering how we target or even prevent distinct populations of cells that pose the biggest threat.” – Dr Samra Turajlic, chief investigator of TRACERx Renal

Central cells more likely to spread

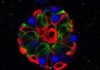

scientists led by the Litchfield lab at UCL and the Turajlic, Swanton, and Bates labs at the Crick analysed 756 kidney cancer biopsy samples from different regions within tumours, taken from the TRACERx Renal study.

They discovered cells at the centre of tumours have a less stable genome – which includes all the genetic material of an organism – and are more likely to spread to other areas of the body. In comparison, cells at the edge of the tumour lower rates of growth and genetic damage.

Samra Turajlic, chief investigator of TRACERx Renal, explained that cancer spread is one of the “biggest barriers to improving survival rates”.

“In the context of the TRACERx Renal Study we previously resolved the genetic make up of different tumour areas, but until now, there has been no understanding of how these differences relate spatially,” she said. “The most critical question is the part of the tumour from which cancer cells break away and migrate making cancer incurable.”

A ‘critical foundation’ for tackling aggressive cancer

The new discoveries have exposed the tumour’s centre as the key to locating its most aggressive cells. This, study authors say, has highlighted the need to develop treatments that target the unique environmental conditions found within the tumour core in order to eliminate them.

Kevin Litchfield, paper author and group leader at the UCL Cancer Institute, said: “Cancer cells in the central zone of the tumour face harsh environmental conditions, as there’s a lack of blood supply and oxygen.”

He pointed out this also means they are more likely to successfully evolve into cells that can spread widely and take hold in distant organs.

Samra Turajlic added: “Our observations shed light on the sort of environmental conditions that would foster emergence of aggressive behaviour. These findings are a critical foundation for considering how we target or even prevent distinct populations of cells that pose the biggest threat.”

Delving even deeper

The scientists also studied how genetically different populations of cancer cells grow within a tumour. By using a unique map building tool to reconstruct the growth of tumour cells, they were able to make another surprising discovery.

Although most tumours follow a pattern where populations of cells grow in the local area, such as a plant growing up and outwards, they found two cases with a “jumping” pattern. It appeared as though these cells had taken hold in a new part of the tumour by jumping over other populations of tumour cells.

The researchers now plan to reconstruct ‘3D tumour maps’ which will allow them to see the spatial patterns within tumours even more clearly.

The study was also funded by the Royal Marsden Renal Unit, Biomedical Research Centre at the Royal Marsden and Institute of Cancer Research, Rosetrees Trust, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation H2020.

References

Zhao, Y et al. (2021) Selection of metastasis competent subclones in the tumour interior. Nature Ecology and Evolution. DOI: 10.1038/s41559-021-01456-6