May 16, 2019, by NCI Staff

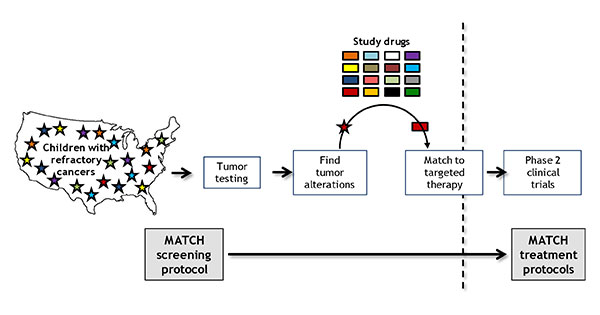

In Pediatric MATCH, a patient’s tumor is screened for genetic alterations that match one of the targeted drugs being tested in the trial.

Credit: D. Williams Parsons, M.D., Ph.D. / Baylor College of Medicine

An early report from a large precision medicine trial of children, adolescents, and young adults with advanced cancer shows that 24% of young patients who had their tumors tested for genetic changes were eligible to receive one of the targeted therapies being tested—much higher than the 10% scientists had projected.

The nationwide trial, known as NCI–COG Pediatric MATCH, is treating patients on the basis of the genetic alterations in their tumors, rather than the type of cancer or cancer site.

Launched in 2017, Pediatric MATCH is one of the first large pediatric clinical trials to systematically test drugs that target specific genetic changes in cancers occurring in children, adolescents, and young adults, said NCI study chair Nita Seibel, M.D., of NCI’s Cancer Therapeutics Evaluation Program.

The NCI-funded trial was developed and is led jointly by NCI and the Children’s Oncology Group (COG).

Because pediatric cancers, on average, have fewer genetic changes than adult cancers, researchers were concerned about whether enough changes could be found to make a trial such as Pediatric MATCH feasible, explained COG study chair D. Williams Parsons, M.D., Ph.D., of Baylor College of Medicine.

But, to date, that concern has not been borne out.

“Pediatric MATCH is showing that a precision medicine approach can be studied in the pediatric setting on a large scale,” said Andrew Bukowinski, M.D., of Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, one of about 200 COG sites enrolling patients in the study.

Dr. Parsons presented the findings at a May 15 press briefing ahead of the 2019 annual meeting of the American Clinical Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), being held May 31–June 4 in Chicago.

An Evidence-Based Approach for Matching Patients to Treatments

Pediatric MATCH is enrolling children, adolescents, and young adults 1–21 years old with advanced solid tumors whose cancer has gotten worse while on treatment or has come back, or relapsed, after treatment.

The trial’s initial screening step uses a single test that looks for changes in more than 160 genes associated with cancer that can be targeted by one of the drugs being tested in the study. Researchers plan to screen at least 1,000 to 1,500 pediatric patients for the trial, Dr. Seibel said.

Those patients whose tumors have a genetic change that can be targeted by a drug included in the study may then go on to the second step of the trial, which is to enroll in the treatment group, or arm, for that drug. Ten drugs are being tested now and more will be added as the study continues.

A key feature of the trial, Dr. Seibel noted, is the use of a computer algorithm that considers the strength of available scientific evidence when deciding whether to include a specific drug as part of the study and when matching eligible patients to one of the study drugs.

The drugs being tested in the trial, all but one of which are still experimental for use in children and adolescents, are being donated by pharmaceutical companies that have partnered with NCI.

At the briefing, the researchers reported that, as of the end of 2018, 422 patients, from nearly 100 sites, had enrolled in the screening step of the study, and tumor testing had been completed for 357 patients (92%).

Genetic changes targeted by one of the 10 study treatments were identified in 112 patients (29% of the screened group), and 95 of those patients (24% of the screened group) were found to be eligible for assignment to one of the treatment arms.

The finding that 24% of the patients screened were eligible for assignment to a trial arm was a surprise. The researchers had anticipated that no more than 10% of the screened patients would be eligible, based on experience from genetic analyses of newly diagnosed pediatric cancers.

One possible reason that potentially targetable alterations are being found in more patients than researchers had predicted is that children with cancers that have returned or do not respond to standard therapies may develop more genetic changes than they had at diagnosis, Dr. Parsons said.

Another possibility, he said, is that “the clinicians who enroll patients on Pediatric MATCH may already know whether their patients are likely to have mutations that make them eligible” for one of the study treatments. That’s because genetic testing of tumor samples in children with cancer has become more common, he said.

Continuing to Expand Pediatric MATCH

Of the 95 patients eligible for one of the study’s 10 treatment arms, 39 patients had enrolled in an arm as of the end of 2018. Each treatment arm is testing the safety of, and tumor response to, a single targeted therapy, and researchers plan to enroll at least 20 patients per arm.

For numerous reasons, not all patients who are eligible to be assigned to one of the experimental treatments will actually enroll on a treatment arm, Dr. Seibel said.

For example, the drug may come only in pill form and the patient may not be able to swallow pills. Or the child’s own physician may enroll a patient for the screening step of the trial while that patient is still taking and responding to another treatment.

All patients enrolled in one of the treatment arms can continue to receive the study drug as long as their tumors are getting smaller or not growing.

“If their cancer starts to progress, then they can be re-screened to see if there are any other genetic alterations that match with one of the other treatment arms. If so, they will be offered the option to go on that arm,” Dr. Seibel said.

“We are continuing to expand Pediatric MATCH so that as many children and adolescents as possible will potentially benefit from it, if they’re screened,” she continued. Investigators plan to keep adding new targeted therapies to the trial based on evidence from other research, including studies with adult patients, she added.

Study arms for four additional drugs, which target genetic changes that are less common than those now included in the trial, are already under development, Dr. Seibel said. “And whenever we add a new treatment arm, we screen all the patients who were previously enrolled in the screening step and are still on the study to see if any of them are eligible for the new arm.”

Keeping Expectations Realistic

Pediatric MATCH is also yielding information on the types and range of genetic changes seen in advanced pediatric cancers and the frequency with which those changes occur.

These analyses may reveal genetic alterations in certain tumor types that researchers might not have known about before, Dr. Bukowinski said. It may also “give us a better understanding of some of the genetic changes that are driving these pediatric cancers,” he added.

Although Pediatric MATCH is enrolling only patients whose cancer does not respond to other treatments or has come back, study investigators hope the trial ultimately will lead to the availability of therapies that can be used in pediatric patients with less-advanced disease.

“The initial goal is to figure out which of these targeted therapies can provide some benefit to patients,” said Dr. Parsons. “Then we can further study how they work for individual cancer types or in other scenarios, such as incorporating them as part of combination therapies or as up-front treatment” for children and adolescents newly diagnosed with cancer, he explained.

“We’re very excited about these types of precision medicine approaches, but we’re still figuring out how to make them most useful for pediatric patients,” Dr. Parsons continued. Therefore, he said, “we have a significant obligation to make sure that the expectations of pediatric oncologists, as well as our patients and their families, are as realistic as possible.”