, by NCI Staff

The results from a recent study establish a new standard for treating children and young adults newly diagnosed with fast-growing forms of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, including Burkitt lymphoma.

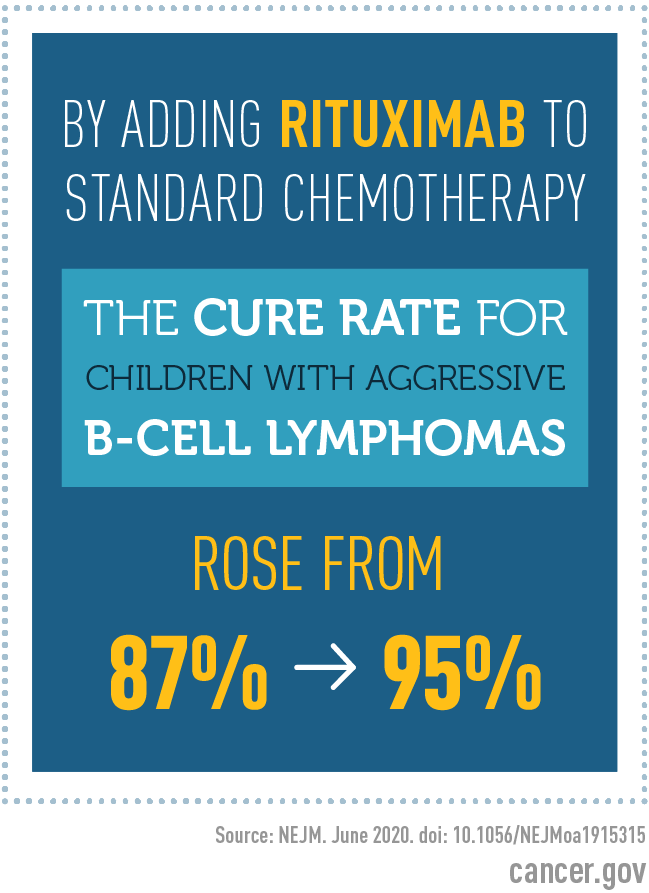

In the study, adding the drug rituximab (Rituxan, Truxima) to standard chemotherapy improved the overall cure rate in these patients from approximately 87% to 95%.

The new treatment regimen “is a remarkably effective therapy for a group of children who have a very aggressive form of lymphoma,” said Malcolm Smith, M.D., Ph.D., of NCI’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, who was not involved in the study.

“To achieve 95% survival for these patients is an outstanding result and a very important accomplishment,” Dr. Smith added.

Findings from the international study, which was led by the NCI-supported Children’s Oncology Group and the European Intergroup for Childhood Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, were published June 4 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Moving the Needle on Survival Rates

Childhood non-Hodgkin lymphoma is a disease in which cancer cells form in the lymph system, which is part of the body’s immune system. B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma begins in white blood cells called B lymphocytes. In children, B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma is often a very aggressive, fast-growing disease, and most cases are Burkitt lymphoma, said Thomas Gross, M.D., Ph.D., of Children’s Hospital Colorado, one of the lead authors on the new study.

The development of intensive chemotherapy regimens for pediatric Burkitt lymphoma, which use high doses of cancer drugs given over several months, increased the cure rate for these relatively rare cancers from about 30% in the 1970s to 85% in the 1990s for children with the most serious cases, Dr. Gross said.

“But to get those kinds of improvements we had to really intensify the chemotherapy,” and any further intensifying could lead to more treatment-related deaths, he continued. So, to further improve treatment outcomes, researchers needed to find and test less-toxic drugs that could be given in addition to chemotherapy.

Rituximab—a type of immunotherapy that targets cancerous B cells as well as normal B cells—was a good candidate because earlier studies showed that adding this drug to chemotherapy helped adults with B-cell lymphoma live longer, Dr. Gross explained.

Benefits of Adding Rituximab Are Clear

To enroll enough children with B-cell lymphomas in the type of large clinical trial needed to rigorously test the potential benefit of adding rituximab to chemotherapy, Dr. Gross and his colleagues forged a collaboration involving a dozen countries in North America, Europe, Asia, New Zealand, and Australia.

Patients ranging from 2 to 17 years old were randomly assigned to receive either the standard regimen of intensive chemotherapy or the same chemotherapy regimen plus six doses of rituximab given over the course of treatment.

Researchers had originally planned to enroll about 600 patients in the study. However, it was stopped early, after enrolling only 328 patients, because a preplanned interim analysis of patient data showed such a clear benefit for rituximab. Halting the trial meant that the randomized part of the trial was stopped and all children who were not receiving rituximab were allowed to receive it, Dr. Smith said.

Of the 328 patients randomly assigned to chemotherapy only or to chemotherapy plus rituximab, 287—or nearly 90%—had Burkitt lymphoma. Three years after starting treatment, the event-free survival rate was 82% with chemotherapy alone and 94% with chemotherapy plus rituximab. Event-free survival means that these patients had not seen any sign of their cancer’s return or progression, developed a second cancer, or died from any cause.

The percentage of patients still living after 3 years (overall survival) was 87% with chemotherapy alone and 95% with rituximab plus chemotherapy. Children with aggressive B-cell lymphoma who survive for 3 years without the disease coming back are generally considered cured, Dr. Smith said.

Most Side Effects Are Temporary

Severe side effects, such as infections and febrile neutropenia, occurred in 24% of patients in the chemotherapy-only group and 33% of patients in the rituximab–chemotherapy group.

Three patients in each group died from treatment-related effects. However, Dr. Smith said, “most children were able to tolerate the treatment, and most of the side effects were reversible.”

“Children who received rituximab had more infections during treatment, but we were able to treat them successfully,” Dr. Gross said. “Because rituximab attacks normal B cells as well as tumor B cells, it will be important to follow these children long term to make sure that their immune systems return to normal function.”

Results from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study published last year show that the intensive chemotherapy regimen used to cure children with aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma does not have many long-term effects that would affect a person’s quality of life, Dr. Gross noted.

Challenges for Treatment in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

Despite the high cure rate achieved by adding rituximab to chemotherapy, Dr. Gross said, “we still need to find treatments for the 5% of patients who aren’t cured with this therapy,” because once the disease comes back there are no good treatment options.

In addition, he noted, only about 10% of all children worldwide who have Burkitt lymphoma and other aggressive B-cell lymphomas live in countries that have sufficient resources to allow them to get potentially curative treatments and the supportive care needed to manage severe side effects of intensive chemotherapy. Burkitt lymphoma has been linked to infection with the Epstein-Barr virus, particularly in Africa, where this virus causes most cases of the disease.

Cure rates for children with aggressive B-cell lymphomas are markedly lower in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) than in high-income countries like the United States, said Monika Metzger, M.D., of the Department of Global Pediatric Medicine at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

In Central America, for example, inadequate supportive care results in more patients dying from treatment-related complications, while others die due to abandonment of therapy or from disease that comes back because the intensive therapy needed for a cure could not be administered, she said.

“It is conceivable that the addition of rituximab could allow for a reduction of [toxic] chemotherapy” in children with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, the study authors wrote. But more data are needed before that possibility can be explored.

“Trials in LMICs, where very intensive chemotherapy is not tolerated and more than 10% of patients die from toxicity, could provide an opportunity to examine which patients can be cured with less intense chemotherapy when rituximab is added,” Dr. Metzger said.

Unfortunately, she noted, rituximab is either not readily available or unaffordable in many LMICs. “This needs to change, so that all children with an otherwise highly curable cancer have access to a potential cure,” she concluded.