, by NCI Staff

Cancer researchers are exploring all kinds of new and creative approaches to immunotherapy, treatments that help the immune system fight cancer. The latest involves nanoparticles that trains immune cells to attack cancer.

The nanoparticles, which are made mostly of substances found in the human body, slowed the growth of melanoma in mice, the NCI-funded study showed.

The human immune system is split into two branches. The innate branch, which is the body’s first line of defense, launches a quick and general response to all kinds of germs. The adaptive branch, which includes T cells and antibodies, kicks in later and has a long-lasting and more specific response to germs.

Most immunotherapies in use today engage the adaptive immune system. What’s novel about the newly developed nanoparticle is that it alters the innate immune system, pushing it into a temporary state known as trained immunity.

Trained innate immune cells are “more alert, so they respond more efficiently to infections and cancer,” explained lead investigator Willem Mulder, Ph.D., of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

The innate immune system can stay in this trained state for months to years, giving the researchers reason to believe that the anticancer effects of the nanoparticle may last for a while. The study findings were published October 29 in Cell.

“Nanoparticles made from materials foreign to our bodies can cause unwanted side effects or unintended accumulation and damage to vital organs. But this nanoparticle is biologically friendly,” said Christina Liu, Ph.D., of NCI’s Nanodelivery Systems and Devices Branch, who was not involved in the study.

Dr. Mulder and his colleagues are hoping to start a clinical trial to test the nanoparticles in the near future. They are currently working on follow-up studies needed to gain approval for human studies.

Engineering a Nanoparticle

In 2016, Dr. Mulder sat in the office of Mihai Netea, Ph.D., of Radboud University Medical Center in the Netherlands, and sketched an idea on a piece of paper.

The pair had recently developed a nanoparticle therapy that inhibits trained immunity. In mice, the nanoparticles prevented the immune system from rejecting an organ transplant.

This time, Dr. Mulder recalled, “Dr. Netea essentially asked me to do the opposite” and design a nanoparticle that triggers trained immunity. The scientists reasoned that such a nanoparticle could potentially be used to treat cancer.

Dr. Mulder, who is a biomedical engineer, looked to nature for inspiration. It turns out that the tuberculosis vaccine, also known as the BCG vaccine, can elicit trained immunity. The vaccine, which is based on a weakened version of the bacteria that causes tuberculosis, is also used as a treatment for bladder cancer.

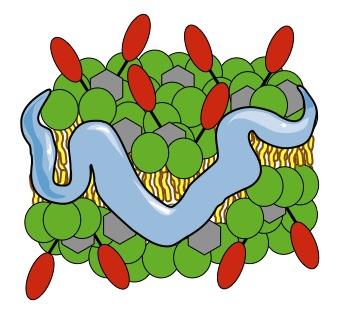

The team engineered a set of nanoparticles using fragments of BCG as well as lipids and proteins from human cells. These proteins help the nanoparticles get to the bone marrow, where innate immune cells are formed. The team refers to nanoparticles made of lipids and these proteins as “nanobiologics.”

Nanoparticles are extremely small—between ten and a thousand times smaller than a single bacterium. Due to their small size, they behave differently in the human body than other chemicals or drugs, Dr. Liu said.

For example, nanoparticles last longer in blood and, depending on their size, accumulate in tumors or certain organs, she explained. And, she added, using natural materials makes the nanoparticle less likely to cause any harsh side effects.

Through a series of lab tests, the researchers identified a specific nanoparticle design that was the best at training innate immune cells grown in dishes. It also had other desired characteristics, such as accumulating in the bone marrow.

Training Immune Cells to Kill Cancer Cells

Next, the team tested those nanoparticle in lab animals, including mice and monkeys.

As intended, the nanoparticle was soaked up by innate immune cells in the bone marrow and spleens of both mice and monkeys. The immune cells then showed several hallmarks of trained immunity. For instance, they divided rapidly, responded quickly to threats, and produced certain chemicals (called cytokines) that ramp up the immune system.

The researchers also tested the nanoparticles in mice with melanoma. These melanoma tumors typically have more procancer immune cells than cancer-killing immune cells—what’s known as an immunosuppressive microenvironment.

But in mice treated with the nanoparticles, the trained immune cells reversed that pattern, leading to more cancer-killing immune cells and fewer procancer immune cells in the tumors.

The treatment ultimately slowed the growth of tumors in the mice, the team found. But they wondered if they could do even better by combining the nanoparticles with another immunotherapy.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are the most commonly used cancer immunotherapy, but they don’t work for every person who gets them. One reason they may not work is if a patient’s tumor has an immunosuppressive microenvironment, Dr. Mulder explained.

“We thought, ‘let’s see if we can induce trained immunity to rebalance the immune system to make it more susceptible to checkpoint inhibitor therapy,’” he said.

As expected, treatment with either of two immune checkpoint inhibitors alone had little to no effect on melanoma tumor growth in mice. However, combining both immune checkpoint inhibitors with the nanoparticle therapy slowed tumor growth much more than any of the checkpoint inhibitors alone.

The nanoparticles also appeared to be safe. They didn’t cause any harsh side effects in either mice or monkeys. Knowing that the treatment was safe in monkeys will make it easier to transition to clinical studies in people, Dr. Mulder said.

Now a biotechnology startup founded by Drs. Mulder and Netea is performing further studies of the nanoparticle that are needed to bring it into human studies. Dr. Mulder and his colleagues are also investigating whether the nanoparticle works for other types of cancer in lab studies.