Maybe you saw the hashtag #DonutTakePAPAway on social media recently? ObGyn physicians and advocates are voicing their disagreement with the American Cancer Society’s (ACS) latest cervical cancer screening guidelines.

You see, this summer while we were worrying about COVID and living during a pandemic, the ACS changed their guidelines for cervical cancer screening. The new guidelines state that cervical cancer screening, beginning at age 25, should be done with a primary human Papillomavirus (HPV) test every 5 years. This eliminated the Pap test from ACS screening recommendations and increased the age to start screening from 21 to 25.

Because the primary HPV tests are not available everywhere yet, they do add that the co-test (which combines HPV and Pap) every 5 years or a Pap test alone every 3 years may be used when the primary test is not available.

Reading that, I thought, this can’t be right! The Pap test has been the driver for drastic reductions in cervical cancer cases and a 70% decline in deaths over the last 50+ years. What is going on here? This sent me on a quest to find out why the change and was it the right thing to do.

Since 2012, the guidelines for screening have been to use Pap testing every 3 years in women ages 21-29 and a “co-test” for women 30-65 every 5 years. The “co-test” combines the traditional Pap test with an HPV test that looks for the 12 types of HPV that are linked to cervical cancer. (More on HPV and cancer on our site) These tests are done at the same time, during the pelvic exam with a speculum. You may not even realize both tests are being done.

The Pap test looks for abnormal cells that can lead to cancer. The problem is that it finds lots of abnormalities that will never become cancer. These findings can lead to additional, anxiety-producing tests (colposcopy being the most common). Because the majority of cervical cancers are caused by HPV, knowing if the woman has a type of HPV that can cause cancer can help decide if more testing is needed.

The new guidelines take things a step further. They use a test called a primary HPV alone, every 5 years, for women 25-65. Studies have found that the HPV test (with or without Pap) does a better job at finding abnormal cells that could turn into cancer. The test can be repeated less frequently (every 5 years instead of every 3 with Pap).

Sounds like a slam dunk – but not so fast. Women’s Health experts have a number of concerns about the changes. The concerns raised include:

- HPV testing alone in younger women could lead to many unnecessary colposcopies due to how common HPV is in younger women.

- Getting a negative HPV result at one time does not guarantee the person will remain negative, even 1 year later. This may give women a false sense of security from a negative result.

- Cervical cancer is rare in women under age 25, but not nonexistent. These cases account for 1% of all cervical cancer cases. This delay in screening may also affect other areas of a young woman’s health that would have been addressed at these visits.

- Shifting to screening every 5 years will likely lead to many women not having other well-women care that would have occurred during an annual visit. This can include breast cancer screening, menstrual health, contraception, fertility and sexuality concerns.

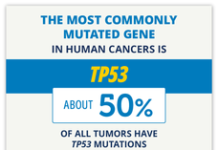

- Remember, not all cervical cancers are caused by HPV. A small number are not – but these would be missed.

The American College of Ob/Gyn Physicians and the USPTF guidelines both still include 3 options for screening, Pap alone every 3 years, co-testing every 5 years, or HPV primary testing every 5 years. Many Ob/Gyn physicians have expressed concern over the change and the risk of missing some cancers.

As a patient, discuss with your provider what test they are doing and what is best for you. You can keep up to date on the debate by following a few women’s health providers on Instagram – there are many, but a few I have found helpful include Jessica Sheperd, MD (@jessicasheperdmd), Kameelah Philips, MD (@drkameelahsays), and Karen Tang, MD (@karenttangmd). You can also check out this petition which outlines the concerns of women’s health providers and the references below to learn more.

References:

National Cancer Institute: ACS’s Updated Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines Explained. September 2020.

ACS Updates Guidelines for Cervical Cancer Screening. Cancer Network. August 4, 2020.

Castanon, A., Landy, R., & Sasieni, P. D. (2016). Is cervical screening preventing adenocarcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma of the cervix?. International journal of cancer, 139(5), 1040-1045.

Flanagan, M. B. (2018). Primary high-risk human Papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening in the United States: is it time?. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, 142(6), 688-692.

Fontham, E. T., Wolf, A. M., Church, T. R., Etzioni, R., Flowers, C. R., Herzig, A., … & Kim, J. J. (2020). Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.

Li, N., Franceschi, S., Howell‐Jones, R., Snijders, P. J., & Clifford, G. M. (2011). Human papillomavirus type distribution in 30,848 invasive cervical cancers worldwide: Variation by geographical region, histological type and year of publication. International journal of cancer, 128(4), 927-935.

Huh, W. K., Ault, K. A., Chelmow, D., Davey, D. D., Goulart, R. A., Garcia, F. A., … & Schiffman, M. (2015). Use of primary high-risk human Papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance.

Austin RM. HPV primary screening: unanswered questions. Cytopathology. 2016;27(1):73–74.

Chenault, C. New cervical cancer screening guidelines ignore past progress. Medcitynews.com. September 30, 2020.

Carolyn Vachani is an oncology advanced practice nurse and the Managing Editor at OncoLink. She has worked in many areas of oncology including BMT, clinical research, radiation therapy and staff development. She serves as the project leader in the development and maintenance of the OncoLife Survivorship Care Plan and has a strong interest in oncology survivorship care. She enjoys discussing just about any cancer topic, as well as gardening, cooking and, of course, her sons.