“It’s a huge achievement by lots and lots of people. It’s nice to think that this next generation will probably never really have to worry about cervical cancer in this country.”

Last year, a monumental moment on a cold November day saw the publication of a long-awaited study.

The results of that study, published in the Lancet, and carried out by our researchers, found that the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine was shown to dramatically reduce cervical cancer rates by almost 90% in women in their 20s who were offered it at ages 12 to 13.

Professor Peter Sasieni

Professor Peter Sasieni

Peter Sasieni, lead author on the paper and based at Kings College London, has been researching cervical cancer for the majority of his career.

“My immediate reaction was that we better check this – it’s too good to be true,” he says, when reflecting on the outcome of the study. “I thought that we might be reducing cases of cancer by 50%. And then to see over 80% reduction is just stunning.”

This year, to celebrate 20 years of Cancer Research UK and 120 years of lifesaving research, we’ve been looking back in time and digging into the archives to explore some of the impact we’ve had in cancer research.

From helping to strengthen the understanding of the link between HPV and cervical cancer, to working towards reducing cervical cancer to the point where almost no one develops it, our history with this particular disease goes way back.

Looking for a link

The first suggestion that cervical cancer was linked to HPV flew in the face of dogma at the time. The discovery caused a stir because, at that point, most scientists didn’t think any common cancers could be caused by a virus.

German virologist Harold zur Hausen had read reports from doctors about women with genital warts also developing cervical cancer, and had also heard about the work of US researcher Richard Shope from the 1930s, showing that infection with a type of papillomavirus could cause warts and cancers in rabbits. He figured that a similar virus might be responsible for human cancers and set out to find it.

After testing cervical cancer samples for HPV, it became apparent that there were many different types of the virus (in fact, there are over 100 variations). In the early 1980s, zur Hausen and his team continued their search and discovered HPV-16, which their small studies detected in about half of cervical cancers samples (35-61%), then HPV-18, present in around one in five cervical cancer samples (15-25%), although there was some variation between countries.

100vw, 200px”></p>

<p class=) Electron microscopy image of HPV Credit: Dr Graham Beards, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Electron microscopy image of HPV Credit: Dr Graham Beards, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

It was coming into sharp focus that infection with these 2 types of HPV was closely linked to cervical cancer – a discovery that eventually won zur Hausen a Nobel Prize in 2008.

This work demonstrated that HPV is a ‘necessary but not sufficient cause’ for cervical cancer – meaning the cancer cannot develop in the absence of HPV, though having HPV does not mean cancer will definitely develop. And to this day, the relationship between cervical cancer and HPV is unique – no other risk factors have been identified as a necessary cause of cancer.

But despite zur Hausen’s discovery, it wasn’t always smooth sailing, and it took decades of work and researchers from all over the world to eventually reach the pivotal moment we saw just last year.

Building a body of evidence

About a decade after the link between HPV and cervical cancer had first been established, Sasieni found himself in an unusual situation.

“I was giving a talk at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, as a young researcher, to a fairly big audience for me at that age, and the person chairing it, I think, just to be provocative, said, ‘Okay, let’s take a vote. How many people believe Peter, that HPV is a cause of cervical cancer’ And the majority of the audience voted to say that they didn’t believe HPV caused cervical cancer,” he recalls.

“These were gynaecologist seeing patients with cervical cancer regularly. And they weren’t convinced by the evidence at that point.”

But things were changing behind the scenes as a body of evidence was mounting.

Between 1987 to 1995 Professor Karen Vousden, our former chief scientist, led the HPV group at the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research in Oxford. Her work pinpointed the specific viral molecules required by HPV-16 to enable cells to continually reproduce and cause cancer.

Around the same time, the International Biological Study on Cervical Cancer group (part funded by our predecessor Cancer Research Campaign) was set up to look at cervical cancer on a global scale. Using samples from 22 countries, they found HPV in more than 9 out of every 10 cervical cancer samples – 93% – and this figure was similar across the globe.

But even this number turned out to be an underestimate.

There is one paper in particular, published in 1999, that Sasieni cites as having a huge impact. A group which included one of our scientists, Julian Peto, diligently dissected nearly 1000 cervical cancer samples collected from around the world.

These results showed that HPV was present in 99.7.% of the samples that could be analysed.

HPV and cervical cancer – the basics

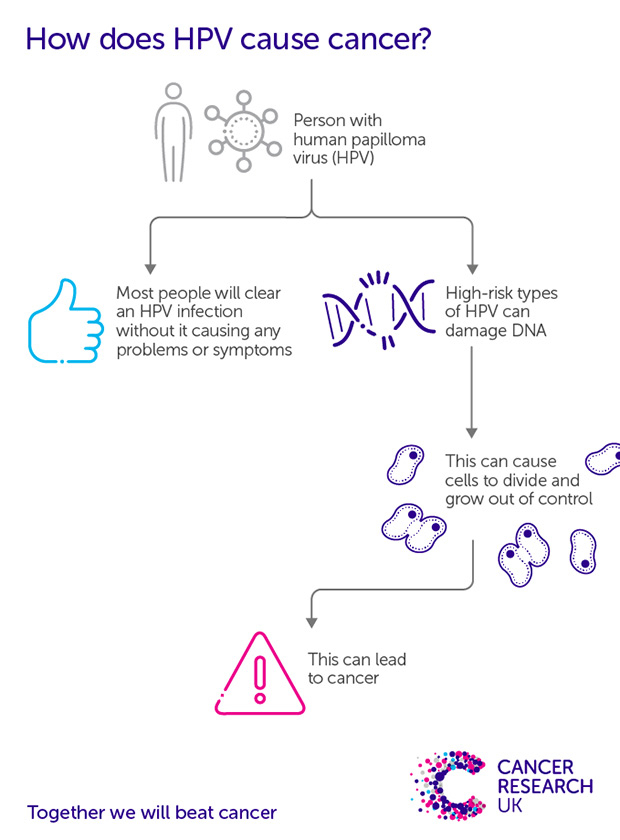

HPV is extremely common, infecting the skin and the cells lining the inside of the body. Most people will have an HPV infection in their lifetime, but most of the time HPV infection doesn’t cause any problems and clears up by itself.

It’s only when certain types, or strains, of the virus can’t be fought off by the body’s immune system that they can cause damage that can lead to cancer.

HPV 16 and 18 cause at least 7 in 10 cervical cancer cases in every country in the world. HPV infection has been linked to other cancers too, including anal, penile, vaginal and vulval cancers, and some mouth and throat cancers.

Copy this link to share our graphic. Credit: Cancer Research UK

“Things changed in the lifetime of a lot of people, certainly in the medical community, if not the scientific community. People went from not being convinced that HPV was a cause of cervical cancer, to establishing beyond any doubt that it’s a cause.

“But people always say that the ultimate test of whether something is a cause is that if you then take that factor away, do you see a reduction?”

So, whilst the link between HPV and cancer had been validated, the next question was whether a vaccine to prevent HPV, and in turn cervical cancer, would be possible.

Underpinning research into the HPV vaccine

The UK first introduced HPV vaccination in 2008, with girls aged 11-13 offered the vaccine in a schools-based programme. Since September 2019, boys of the same age can also get the vaccine, and a catch-up programme is now available to women up to their 25th birthday.

In addition to the schools-based programme, the HPV vaccine programme has also been available to men who have sex with men aged 18-45 through sexual health and HIV clinics since 2016. This has since been extended to cover some trans and non-binary people.

The development of the HPV vaccine was ultimately led by pharmaceutical companies, but the groundwork and scientific theory behind the vaccines was laid by scientists and clinicians, including many of our own.

The vaccine against HPV had unusual beginnings. In the 1950s, vets were looking for a vaccine for cattle to protect them from bovine papillomavirus, which can cause tumours in cows.

This research turned out to be relevant to human disease too – our researchers in the Beatson Institute in Glasgow proved that a vaccine containing a molecule very similar to one made by HPV 16 protected calves from infection, providing solid grounds for investigating a human vaccine.

The two scientists widely credited with developing the HPV vaccine are Professor Ian Frazer and Dr Jian Zhou, although others also carried out pivotal research in this area. The pair came up with the basis of the vaccine in Queensland, Australia, but they met and began their studies on an HPV vaccine in Cambridge while they were working in Professor Lionel Crawford’s lab. Crawford was a Cancer Research UK scientist and an expert on cancer and virology (most famous for his partnership with Professor David Lane and their discovery of p53, the “guardian of the genome”).

100vw, 620px”></p>

<p class=) Syringe containing HPV vaccine Credit: Ted Eytan, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Flicker

Syringe containing HPV vaccine Credit: Ted Eytan, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Flicker

A wave of studies, including a number authored by our scientists, confirmed that HPV vaccination is effective in preventing HPV infection, genital warts, and high-grade precancerous cell changes in the cervix.

But as the vaccine was only introduced in the 2000s, it hasn’t been possible until recently to definitively say that the vaccine also reduces cases of cervical cancer – the ultimate goal of the vaccination program.

One study, coming from research conducted in Sweden, found that HPV vaccination resulted in a 63% lower risk of cervical cancer incidence in vaccinated women by age 30, when compared to unvaccinated women.

It wasn’t until last year that the full scale of England’s vaccination programme success was realised, when Sasieni and colleagues published a paper showing that the bivalent HPV vaccine (which protects against HPV 16 and 18) dramatically reduced cervical cancer rates by almost 90% in women in their 20s who were offered it at age 12 to 13.

But the HPV vaccine on its own wouldn’t be enough to protect generations from cervical cancer. All the while, scientists and clinicians were also developing and adapting a national screening programme.

Cervical cancer screening

People often credit the key paper advocating for cervical screening as Papanicalaou and Traut, who published their study during the Second World War.

“People say it didn’t really have the impact it should have because it was published during the war,” says Sasieni. But fundamentally, that paper was seen as the first to suggest that from a small sample of cells from the cervix, known as a cytology test, we could identify cancer and that there isn’t need for a whole biopsy.

100vw, 200px”></p>

<p class=) Cervical cancer cell

Cervical cancer cell

Cervical screening was formally introduced in England in 1964, but it was rolled out in a ‘haphazard’ way.

“It was not properly organised and there was no quality management,” adds Sasieni, “I don’t think there was any guidance on how to take a smear, and there was probably very little standard on cytology testing and reading cytology.”

The flaws of this approach became apparent in the mid-1980s and led to the creation of the National Health Service Cervical Screening Programme (NHSCSP) in 1988. Almost immediately, cervical cancer mortality rates began to fall and by the end of the 20th century cervical cancer in the UK was about half as common as it had been.

The screening programme for cervical cancer continued to adapt as the evidence continued to evolve, including a critical switch in the type of test used.

Switching to primary HPV testing

Even when cells in the cervix show up as abnormal, it doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll lead to cancer – sometimes, abnormal cells can disappear on their own accord and don’t need treating. So, researchers wondered whether there was a way to predict which abnormal cells were at higher risk of developing into cancer, and which were more likely to disappear untreated.

From the early 2000s onwards, our scientists proved that testing for HPV before testing for cell changes (known as primary HPV testing) could be a more effective warning system for preventing cervical cancer than the traditional cytology test.

100vw, 200px”></p>

<p class=) Liquid based cytology test

Liquid based cytology test

A cytology test looks at cervical cells in the sample first and aims to detect any unusual changes that could be precancerous.

In 2003, a study funded by us and led by Professor Jack Cuzick, suggested that testing for HPV first could be used for primary screening in women older than 30 years old, with cytology then used to triage HPV-positive women.

But implementing change was a slow process.

“Liquid based cytology (instead of the conventional ‘pap smear’) was introduced in 2003 and primary HPV testing wasn’t introduced for another 5 or 6 years. I think it’s because they’ve just had this major upheaval to introduce liquid based cytology, that they then didn’t want to introduce primary HPV testing.”

In 2017, Sasieni himself presented research that showed that the introduction of primary HPV testing into the cervical screening programme could prevent around 24% of current cervical cancer cases in women invited for screening in England. This figure is equivalent to 487 cancers per year, based on 2013 incidence figures.

“That paper highlighted the need to implement things more quickly, calling for that change to happen as soon as possible.”

Early on in 2019, the results of an NHS pilot study, supported by us, to test the feasibility of primary HPV cervical screening in a real-life setting, revealed that a switch to HPV screening is effective.

This eventually led to primary HPV screening being rolled out in Wales in 2018, in England at the end of 2019 and in Scotland in 2020. These changes led to a call for cervical screening intervals to be extended, a recommendation which has already been adopted in Wales and Scotland. Although Northern Ireland has not moved to HPV primary testing, we hope this change will be implemented soon.

Testing for HPV first is a much more effective way of screening. So much so that the same benefits of cervical screening can be delivered even with larger gaps between screens.

This May, a new study which was part funded by Cancer Research UK used real-world data to confirm that HPV testing as the first-line test on cervical samples is more accurate at predicting who is at risk of developing cervical cancer. It found that in women under 50, those who tested negative with HPV testing were significantly less likely to develop abnormal cells or cervical cancer by their second screen than those who tested negative with cytology testing. Alongside previous research, this showed that the time interval between screens can be safely extended for those who test negative for HPV.

Cervical cancer screening – the basics

‘HPV primary testing’, the process used in most of the UK, involves a health professional, usually a practice nurse, taking a sample from the cervix which is then sent off to the lab.

The laboratory will then check for HPV types linked to cancer. If HPV is found, the laboratory will test the sample for abnormal cell changes.

Cervical screening is for anyone with a cervix aged 25 to 64, including some trans and non-binary people. The screen is routinely carried out by a health professional at your GP surgery, a sexual health clinic or other specialist clinics.

Cervical cancer on a global scale

Despite the success of the HPV vaccine, the story is far from finished.

“Between vaccination and various forms of screening, we really do have the tools to tackle cervical cancer globally. And I think it’s imperative that we do,” says Sasieni.

The World Health Organisation’s strategy to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health problem has outlined a powerful case and a range of effective measures for reducing cervical cancer incidence and mortality. But in order to achieve the target of eliminating the disease as a public health problem, financial commitments, political will, and public demand are all essential, and each of these aspects requires a context-specific and culturally relevant approach.

“You can’t just say one size fits all for how you should implement this strategy worldwide. Because there are a whole variety of things that need to be considered, from healthcare priorities, to infrastructure, to international trade” confirms Sasieni.

That’s why we’re researching techniques and methods that could play a role in overcoming some of these obstacles.

The future of preventing cervical cancer

We are supporting research to ensure more people globally are able to be vaccinated against HPV. We are proud to be co-funding — with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the National Cancer Institute — the PRIMAVERA trial in Costa Rica. The trial tests the protective immunity of a single dose of the HPV vaccine, which would largely reduce the cost and streamline the logistics of vaccination programmes globally.

The evidence on a single dose regimen of HPV vaccine is rapidly growing, and it is likely that one dose of the HPV vaccine provides comparable protection against HPV infection and cervical cancer as two doses. Based on this, the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation, who advises UK health departments on immunisation, has recently advised that children taking up the vaccine, and for men who have sex with men up to the age of 25, are given 1 dose rather than 2. A 2-dose schedule has been advised for men who have sex with men over 25, and 3-doses for immunosuppressed individuals and those who are HIV-positive.

On a global scale, moving to a single dose schedule could be a huge step in ensuring equitable access to the HPV vaccine across the world.

We also fund policy research and advocacy in low- and middle-income countries to ensure that, through increased access to and uptake in HPV vaccination, a future in which almost no one develops cervical cancer can be a reality all over the world

Some of our researchers are also looking into the role self-sampling might play. HPV testing of self-collected samples has the potential to overcome several barriers to uptake and may help to reduce inequalities in cervical screening coverage in specific groups of individuals

There’s a whole host of other innovative research going on in the field, explains Sasieni. “Some people are looking at urine samples, others are also looking at whether you could just take a menstrual pad of some sort, and just test the blood there for HPV, so you wouldn’t have to be doing any special sampling,” he says.

“But to implement these, there needs to be a system in place. A large part of screening has got to be that you can actually get the result of the test back to the person who was screened and make treatment available.

“So we need to think about what we can do to see a big reduction in cervical cancer quickly. That means some combination of screening with vaccination because vaccination is if you like, today’s solution for tomorrow. But if we want to see an impact on cervical cancer over the next decade, the next 2 decades, we need to see a combination of vaccination and screening, and of course treatment.”