, by Carmen Phillips

Immunotherapy is likely to become a much more common treatment for women with advanced endometrial cancer, following the release of results from two large clinical trials.

In both trials, combining drugs known as immune checkpoint inhibitors with standard chemotherapy substantially increased how long some people with endometrial cancer lived without their cancer getting worse, a measure called progression-free survival. The improvement in progression-free survival was greatest in people whose tumors had specific genetic changes called dMMR or MSI-high.

Results from both studies were presented at the 2023 annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) on March 27 and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The trials used different immune checkpoint inhibitors—pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and dostarlimab (Jemperli)—and had some other differences in how they were conducted. But the researchers who led the trials and other experts agreed that the findings should change the treatment for people with advanced endometrial cancer and those who initially had endometrial cancer that came back, or recurred, after treatment.

“Both of these trials hit a home run,” said Rebecca Arend, M.D., who specializes in treating gynecologic cancers at the University of Alabama at Birmingham O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center. “Overall, this is a huge win for our patients,” Dr. Arend added during a session on both trials at the SGO meeting.

Neither drug is yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for this specific use. And some gynecologic cancer researchers stressed that there’s still more to learn about how best to use immune checkpoint inhibitors to treat endometrial cancer.

For example, the trial that tested dostarlimab, called RUBY, hasn’t gone on long enough yet to show whether adding the drug to chemotherapy improves how long participants live overall, cautioned Elise Kohn, M.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, who specializes in treating gynecologic cancers. Dr. Kohn spoke at a different meeting on March 27, a virtual plenary session held by the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) that focused on the RUBY trial results. The same holds true for NRG-GY018, other experts noted.

RUBY’s findings, as well as those from several other recent studies, she continued, also suggest that even dMMR endometrial cancers may have important biological differences that may influence whether and the extent to which immunotherapy will work for them.

Nevertheless, Dr. Kohn said, both trials’ findings have “presented … new opportunities” to improve the treatment of endometrial cancer.

Improving outcomes for advanced endometrial cancer

The number of US women diagnosed each year with endometrial cancer has been steadily growing, and it is the only gynecologic cancer with rising death rates.

The increased incidence has been linked with several factors, including the obesity epidemic, while the increasing death rate has been attributed to more women being diagnosed with aggressive forms of the disease than in the past.

Still, most women are diagnosed with endometrial cancer when it’s still early stage, and about 95% of women diagnosed with early-stage disease will live for at least 5 years.

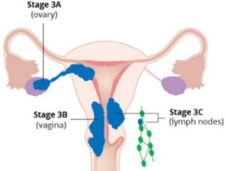

But the long-term outlook for women who are diagnosed with endometrial cancer when it has already spread, or metastasized, beyond the uterus is much less favorable: less than 20% survive for 5 years or more. The long-term prognosis for women with recurrent endometrial cancer is also poor.

The combination of the chemotherapy drugs cisplatin and paclitaxel has long been the standard treatment for women with advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer. But treatment options for these two groups of patients have changed recently, largely because of advances in immunotherapy.

Over the last 2 years, pembrolizumab and dostarlimab were approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat women with advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer whose disease had worsened after initial, or first-line, treatment with chemotherapy.

The results from the clinical trials that led to those approvals set the stage for trials to test whether adding an immune checkpoint inhibitor as part of initial treatment might further extend how long women live without their cancer getting worse and, potentially, overall.

Improved progression-free survival, especially for dMMR tumors

The trial that used pembrolizumab, called NRG-GY018, included more than 800 participants. They were randomly assigned to receive either pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for about 6 months, followed by “maintenance treatment” with pembrolizumab alone for about 21 months or to receive chemotherapy plus a placebo, followed by a placebo alone using the same schedule.

The NRG-GY018 study was supported by NCI, with some funding from Merck, which manufactures pembrolizumab, as part of a formal research agreement.

About 30% of people in NRG-GY018 had dMMR tumors. Among the dMMR group, 74% of participants treated with pembrolizumab were alive without their cancer getting worse 12 months after starting treatment, compared with 38% of those in the placebo group. In the pMMR group, those numbers were 50% and 30%, respectively.

The data were presented by the trial’s lead investigator, Ramez Eskander, M.D., of the John and Rebecca Moores Comprehensive Cancer Center in San Diego.

The RUBY trial included approximately 500 patients, about 23% of whom had dMMR tumors. In the trial, participants were randomly assigned to receive either dostarlimab and chemotherapy for about 6 months, followed by maintenance treatment with dostarlimab alone for up to 3 years, or a placebo plus chemotherapy on the same schedule.

The trial was funded by GlaxoSmithKline, which manufactures dostarlimab.

Patients in RUBY have been followed for much longer than those in the NRG-GY018 trial. In the dMMR group, at 24 months after starting treatment, about 61% of those treated with dostarlimab were still alive without their cancer getting worse, compared with 16% in the placebo group. Although pMMR was not a planned measure (endpoint), in that group, those numbers were 28% and 19%, respectively.

The findings “represent a substantial and unprecedented benefit” in people with dMMR endometrial cancer, said the RUBY trial’s lead investigator, Mansoor Mirza, M.D., of Copenhagen University Hospital in Sweden, at the SGO meeting.

Although more follow-up is needed, Dr. Mirza said, the data for people with dMMR tumors are trending in the direction that indicates that the treatment also improves how long people live overall.

As for safety, neither trial turned up new side effects that haven’t been seen before in people treated with either immunotherapy drug or the two chemotherapy drugs. Nevertheless, people in the immunotherapy groups in both trials had higher rates of side effects, including serious ones. And more people in the immunotherapy groups in both trials had to stop treatment because of side effects.

Both trials also had several deaths in the immunotherapy groups, but most were not considered to be caused by the immunotherapy drug.

Important questions about chemotherapy, biomarkers

Multiple experts on gynecologic cancers agreed that, for people with advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer who have dMMR tumors, adding either pembrolizumab or dostarlimab to chemotherapy should be the new standard first-line treatment.

According to spokespeople for Merck and GlaxoSmithKline, neither company has yet submitted applications to the agency for those approvals.

Although researchers praised the trials’ findings and their potential to improve the care of endometrial cancer, they also identified critical questions that need to be answered moving forward.

These questions include whether chemotherapy is always needed as part of initial treatment and uncertainty about the duration of maintenance treatment.

And although the data are strongest for using immunotherapy as part of first-line treatment for people with dMMR tumors, Dr. Kohn stressed that the findings from both trials strongly suggest that some people with dMMR tumors don’t respond at all to these drugs.

So, finding a molecular marker, or biomarker, in tumors that identifies those that are unlikely to respond will be important, she said. Several recent studies are already providing some important clues along those lines, she added, including studies that suggest that the specific biological mechanism behind faulty DNA mismatch repair in a given patient may affect whether their tumors will respond to immunotherapy.

The flip side of that discussion, and the “elephant in the room,” said Dr. Arend, is “What are we going to do for [pMMR patients]?”

Dr. Mirza pointed out during his presentation at the ESMO session that some pMMR tumors respond very well to immune checkpoint inhibitors. So a biomarker to identify those patients will also be important, he said.

Other ongoing trials are testing other immune checkpoint inhibitors in people with endometrial cancer. Some of those studies are using them in combination with other drugs, including targeted therapies, Dr. Mirza continued.

“This is just the start of the story,” he said, “not the end.”