Craig A. Portell, MD, is an Associate Professor of Medicine at the University of Virginia and a member of the UVA Cancer Center in Charlottesville, Virginia. Dr. Portell treats patients with lymphomas and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and conducts clinical trials in these areas. View Dr. Portell’s disclosures.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy is a type of immunotherapy that modifies a person with cancer’s immune system so it is more effective at finding and destroying cancer cells. A person’s immune system is very complex and involves many different types of cells and systems throughout the body. One of these cells is called a lymphocyte, which is a type of white blood cell that works to fight infection. There are several types of lymphocytes, one of which is called a T cell. T cells are normally responsible for killing cancerous cells and cells infected by a virus, which is why they are used in CAR T-cell therapy. Cancer cells are known to hide from the normal immune system, but through CAR T-cell therapy, scientists are able to make T cells better equipped to find and kill some cancer cells.

How does CAR T-cell therapy work?

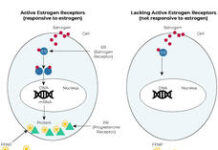

CAR T-cell therapy makes T cells focus their attention toward a substance the body thinks is harmful called an antigen, which is found on the surface of specific cancer cells. In the manufacturing of CAR T cells, a protein is added to the T cell’s surface to help them achieve this focus. This protein is called a chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR. This CAR protein is actually made up of 3 other proteins: 1 protein that recognizes antigens on the cancer cell and 2 proteins that signal the T cell to activate when that first protein attaches to an antigen on the cancer cell. When a T cell has a CAR added to it, it is called a “CAR T cell.” CAR T cells work by floating around the body and looking for cells that carry the antigen programmed into the CAR protein, like certain cancer cells.

When a CAR T cell comes in contact with an antigen on a cancer cell, it activates. Activated CAR T cells multiply and signal to other parts of the immune system to come to the site of the cancer cell. These signaling proteins are called cytokines. All of these cytokines and activated T cells then cause significant inflammation focused at the cancer cell, which causes the cancer cell to die. If all of the cancer cells die, the cancer can become in remission, which means the cancer has disappeared either temporarily or permanently.

What is it like when a person receives CAR T-cell therapy?

First, a person with cancer must be referred to a specialized center for this type of therapy. Then, their T cells need to be collected. It is important to know that T cells are often affected by previous cancer treatments and may not be as healthy because of those treatments. Ideally, T cells are as healthy as possible when they are made into CAR T cells. This often means the collection of a person’s T cells needs to be done during a pause in treatment. This means the doctor must carefully make sure that the cancer will not be too active or cause too many symptoms while treatment is paused, so as many healthy T cells are collected as possible. For some types of cancer, this is the most difficult part of the process, and some people may not be eligible for CAR T-cell therapy because of it.

Once a certain amount of time passes without treatment, the T cells are collected through a process called apheresis. During apheresis, the person’s blood is circulated through a machine that filters out T cells and gives the rest of the blood back to the person. These cells are then sent to a manufacturer to be created into CAR T cells, which typically takes about 3 to 6 weeks. During manufacturing, the person’s normal T cells are activated, multiplied, and infected with a virus, which results in genetic modification that adds the CAR to the T cell. The CAR T cells are then frozen and shipped back to the person with cancer’s doctor. While waiting for manufacturing to be complete, the person’s regular cancer treatment can resume.

Before the doctor infuses the CAR T cells into the person with cancer, a short course of chemotherapy called lymphodepletion is given over 2 to 3 days so the normal immune system does not think the CAR T-cells are abnormal and reject them. Then, the CAR T cells are taken out of the freezer, thawed, and infused through the blood, much like a blood transfusion.

This is when the CAR T cells start their activity. They circulate around the body finding cancer cells, activating, multiplying, using cytokines to call in backup, and killing the cancer.

What are common side effects of CAR T-cell therapy?

Too much activation of the immune system, which is called cytokine release syndrome (CRS), can be very harmful to the person with cancer. CRS is typically seen within a few days to 2 weeks after CAR T-cell infusion and stops within days to weeks. CRS affects people receiving CAR T-cell therapy on a wide spectrum. Some people only experience a high-grade fever, some have low blood pressure and/or low oxygen levels, and others need an intensive care unit (ICU) level of care, which may include needing machines to help keep the person alive. However, doctors have become much better at controlling CRS, so being admitted to the ICU after CAR T-cell therapy is not as common. A drug called tociluzumab, which turns off an important cytokine called IL-6, has improved care for CRS. However, CRS is still a risk of CAR T-cell therapy and can be very serious.

Sometimes during CAR T-cell therapy, the cytokines can also affect the brain, causing a symptom called immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS). ICANS also has a range of symptoms, including mild to severe confusion, shaking, or more rarely, seizures. It can also create memory loss. ICANS is almost always associated with CRS and typically occurs later than CRS, usually within 1 to 4 weeks after CAR T-cell infusion. ICANS is reversible, though some symptoms may take longer to resolve.

After about 2 to 4 weeks following a CAR T-cell infusion, the person with cancer is typically “out of the woods” for more severe complications. However, they must still stay near the treatment center for close observation for a period of time as required by their doctor. After about 3 months, the doctor will check to see if the CAR T cells worked.

It’s important to note that CAR T cells kill all cells against which they are directed, including normal cells. This usually results in a weak immune system for several months following treatment. This may lead to rare types of infections usually seen in people with severe immunodeficiencies. A person receiving CAR T-cell therapy must be particularly cautious in this stage of recovery and report a fever or other symptoms to their doctor.

Which types of cancer is CAR T-cell therapy currently approved for?

Approvals around CAR T-cell therapy are rapidly changing. The types of cancer that are currently treated using CAR T-cell therapy are diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in pediatric and young adult patients up to age 25. As of March 2021, 5 CAR T-cell drugs have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Given the serious side effects around CRS and ICANS, all of these approvals are for people whose cancer has returned after receiving at least 1 previous type of therapy, depending on the indication.

There is so much other research being done around CAR T-cell therapy, including studying the use of current FDA-approved products for new indications or in less treated patients and finding ways to make CAR T-cell therapy safer for patients. As research around CAR T-cell therapy continues, many in the cancer community have a lot of hope around the therapy’s future and what it could mean for people with cancer.