, by NCI Staff

A large study has confirmed that a genetic test can correctly predict how likely it is for recurrent prostate cancer to spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body. The test could help people with prostate cancer and their doctors choose the most appropriate treatment, the researchers concluded.

If a person’s PSA level starts to rise after surgery to remove the entire prostate (radical prostatectomy), that generally means the cancer has come back. The standard treatment for prostate cancer that has come back after prostatectomy is radiation therapy, either alone or with the addition of hormone therapy.

Because hormone therapy can cause distressing side effects—including hot flashes, loss of energy, and loss of sexual desire—the treatment is typically reserved for patients with aggressive cancer that is more likely to spread, explained the study’s lead investigator, Felix Feng, M.D., of the University of California, San Francisco.

Most people with recurrent prostate cancer “don’t want hormone therapy unless they absolutely have to receive it,” he added. But it’s currently challenging to determine which patients have aggressive cancer that may require the addition of hormone therapy.

The new study found that the genetic biomarker test, called Decipher, may have the ability to do just that. Using data from an NCI-sponsored clinical trial, researchers found that people with higher Decipher scores were more likely to have cancer that spread years later and to die from the cancer. The results, published February 11 in JAMA Oncology, also showed that hormone therapy helped people with higher scores live longer but was far less helpful for those with lower scores.

Although the Decipher test was developed nearly a decade ago, the new findings are important because previously there wasn’t enough evidence to recommend its routine use in patient care, explained Sean McGuire, M.D., Ph.D., in an accompanying editorial.

The Need for a Better Biomarker

Doctors currently use certain criteria—like the tumor grade and PSA level—to recommend whether patients with recurrent prostate cancer should get hormone therapy in addition to radiation. But studies have shown that these characteristics aren’t very good at identifying people who truly need the combination treatment.

“A patient could have a rising PSA [level] and die of something else” rather than prostate cancer down the road, explained Adam Sowalsky, Ph.D., head of NCI’s Prostate Cancer Genetics Section, who was not involved in the study.

The Decipher test was developed to address the need for a reliable biomarker, and retrospective studies that looked back in time have shown that it does indeed outperform standard markers like PSA level. The test looks at the activity of 22 genes in prostate tumors and calculates a score from 0 to 1.

For the new study, Dr. Feng and his colleagues set out to see how well the test worked in the context of a clinical trial that had followed participants forward in time. They applied the Decipher test to tumor tissue that was removed during surgery from 352 patients who participated in an earlier clinical trial. Of those patients, 89% were white.

The trial participants—who all had rising PSA levels after surgery—had been randomly assigned to receive radiation alone or in combination with bicalutamide (Casodex), a type of hormone therapy. The participants’ medical outcomes had been tracked for about 13 years.

Assessing the Decipher test in the context of this previous trial allowed the researchers to determine whether the test could predict outcomes in patients who hadn’t yet been treated and whether it could predict how well that treatment would work, Dr. Sowalsky explained.

Decipher Test Scores

After accounting for differences in participants’ ages, races, ethnicities, cancer treatments, and other factors, the researchers found that prostate cancer was more likely to have spread in people with higher Decipher scores than in people with lower scores.

“The remarkable piece is that [testing] these samples predicted the development of metastasis 10 or more years before those metastases developed,” Dr. Sowalsky said.

The test scores were also strongly associated with the risk of dying from prostate cancer and dying overall during the study period, the team found.

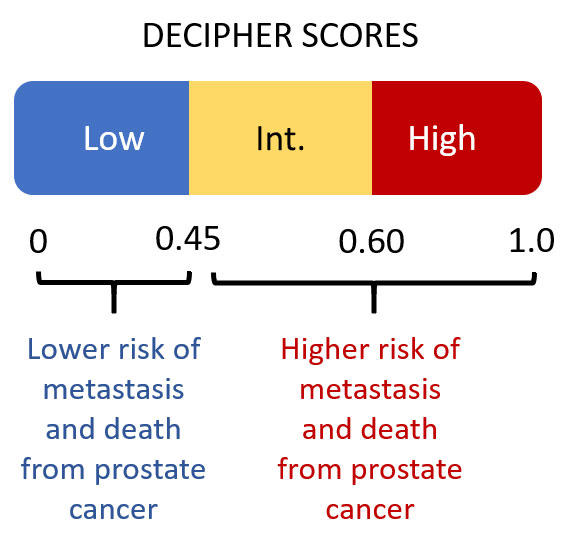

In addition to looking at the scores on a continuous scale from 0 to 1, the researchers also clustered the scores into three previously defined groups: low (scores below 0.45), intermediate, (scores between 0.45 and 0.6), and high (scores above 0.6). Overall, 42% of the men had a low score, 38% an intermediate score, and 20% a high score.

These score groups were also strongly associated with the risk of metastasis, death from prostate cancer, and survival overall, the researchers found. For example, metastasis occurred in 15% of people with high scores but just 6% of people with low scores. And while less than 1% of people with low scores died from prostate cancer, 10% of people with high scores died from the disease.

Having cut-off points for low and high scores can help doctors easily determine the most appropriate treatment, Dr. Feng explained.

Although the study wasn’t designed to detect a relationship between Decipher scores and how well hormone therapy worked, Dr. McGuire noted, the results did suggest that hormone therapy helped people with high and intermediate scores live longer. Hormone therapy also helped people with low scores live longer, but the improvement was minimal compared with what was seen in people with higher scores.

The Decipher test “may identify a subset of patients with a disease [prognosis] that’s so favorable that they don’t need the addition of hormone therapy to radiation,” explained Dr. Feng. Several of the study investigators received fees from or worked for Decipher Biosciences, the company that makes the Decipher test.

Use in Everyday Medical Care

Current guidelines from leading medical organizations (such as the American Society for Clinical Oncology) don’t recommend routine use of the Decipher test. But the new study results should prompt these organizations to reconsider such guidelines “on the basis of the strength of the evidence,” Dr. McGuire wrote. The test’s use in everyday medical practice “should become commonplace,” he added.

The question of whether hormone therapy should be added to radiation for patients with rising PSA after surgery “is a question I see all the time in my practice,” Dr. Feng said. “My patients very much want to know if hormone therapy has a good chance of benefiting them. Tests like this are important because, if we can provide more information to patients and physicians, they can make better choices together.”

Decipher is already available to patients and the cost is covered by many insurance payers, including Medicare, Dr. Feng said. Plus, it doesn’t require an additional procedure if tumor tissue is readily available from the patient’s prostate surgery.

There are still many questions about how to use the Decipher test in different groups of patients with prostate cancer, Dr. McGuire wrote. About 20 ongoing clinical studies are looking to provide some answers.

One area that needs further study is how well the test works in people of color, Dr. Feng noted. Recent evidence has shown that genetic-based tests can be less useful for people of color if there was a lack of diversity among participants in the studies that were done to develop and validate the test.