, by NCI Staff

A type of cancer therapy that delivers radiation directly to cancer cells may represent the newest advance in the treatment of prostate cancer, according to results from a large clinical trial. The trial included participants with a hard-to-treat form of advanced prostate cancer, called metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, that had gotten worse despite treatment with standard therapies.

In the study, participants who received the drug, called 177Lu-PSMA-617, along with other standard treatments lived longer than those who received only standard therapies: a median of 15.3 months versus 11.3 months.

Treatment with 177Lu-PSMA-617—one of an emerging group of cancer therapies called radiopharmaceuticals—did lead to more side effects. In addition, several deaths were attributed to treatment with the radiopharmaceutical. However, the researchers reported that the most common side effects, such as fatigue and dry mouth, were rarely serious and that participants generally appeared to handle the side effects well.

The results from the trial, called VISION, were presented on June 6 at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and published June 23 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study’s findings support making 177Lu-PSMA-617 a “new treatment option for this patient population,” said the trial’s lead investigator, Michael Morris, M.D., of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, during a press briefing at the ASCO meeting.

Several other experts on treating prostate cancer agreed.

Mary-Ellen Taplin, M.D., who specializes in treating prostate cancer at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, called VISION “a very positive trial” and said she believes there will be strong interest among patients and clinicians for 177Lu-PSMA-617.

However, Dr. Taplin, who was an investigator on the trial, also said she was disappointed that adding 177Lu-PSMA-617 to treatment only improved patient survival by several months. “I had hoped for more,” she said.

177Lu-PSMA-617 is not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but Novartis, which manufactures the drug and funded the VISION trial, said that it plans to submit an approval application to the agency later this year.

Targeting PSMA: Not Just for Imaging

Like a number of other radiopharmaceuticals, 177Lu-PSMA-617 has two components: a drug that delivers the therapy to cancer cells and a radioactive particle. In the case of 177Lu-PSMA-617, the delivery vehicle is PSMA-617, a drug that latches onto a protein called PSMA that is often found at high levels on the surface of prostate cancer cells. The radioactive component is lutetium-177, which is being tested as a part of multiple radiopharmaceutical drugs.

As Dr. Morris explained, PSMA-617 is extremely adept at finding and locking on to the PSMA protein on cells. Once it binds to PSMA on a cancer cell, “the whole molecule is internalized by the cell and the cell is exposed to a lethal dose of radiation” from lutetium-177, he said.

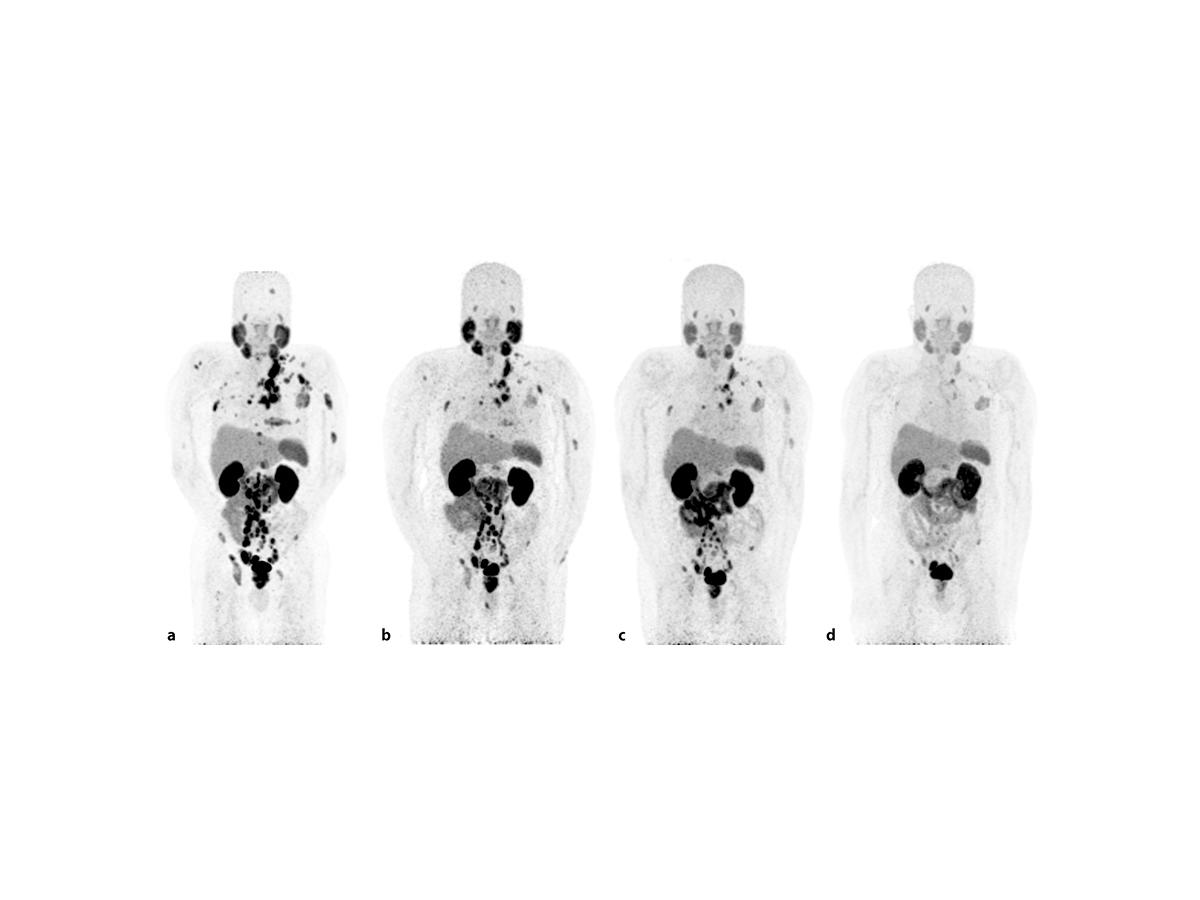

The PSMA protein is also at the heart of a new type of imaging procedure called PSMA PET. This form of PET imaging is just starting to be used in men with prostate cancer to determine whether their cancer has spread, or metastasized, beyond the prostate. In the last several months, FDA has approved two such drugs, known as radiotracers, for PSMA PET imaging. (See box.)

PSMA is often overproduced by prostate cancer cells but is generally not produced by most normal cells, “making it an excellent target for both PET imaging and targeted systemic radiation therapy” like 177Lu-PSMA-617, Dr. Morris said.

Improved Survival, Largely Safe for Patients

The VISION trial enrolled 831 people with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. All of them had previously been treated with chemotherapy and other standard treatments, such as enzalutamide (Xtandi) and abiraterone (Zytiga). In addition, all participants had PSMA-positive tumors—that is, their tumors overproduced PSMA—as determined by PSMA PET imaging.

Trial participants were randomly assigned to receive treatment with 177Lu-PSMA-617 (up to 6 doses) along with their physician’s choice of treatment, which had to be among several commonly used options for cancers no longer responding to other established treatments, or their physician’s treatment choice alone.

Physicians’ choices of treatment could not include chemotherapy or radium-223 (Xofigo), a radiopharmaceutical specifically used to treat bone metastases in patients with prostate cancer. The typical options included enzalutamide or abiraterone (whichever the patient had not received prior to enrolling in the trial) as well as palliative treatments, like radiation and steroids, Dr. Morris explained in an interview. Under the trial’s design, doctors could adapt treatment as they felt necessary.

“We were trying to mirror [treatment] practices in this particular context,” he said. “If the patient needed a change, they could go from one treatment to another.”

In addition to improving how long patients lived overall, participants treated with 177Lu-PSMA-617 also had improved progression-free survival, which is how long somebody lives without their cancer getting worse: 8.7 months versus 3.4 months.

If approved by FDA, Dr. Morris said, 177Lu-PSMA-617 “should become a standard of care for these patients, because there are so few existing treatments that prolong their lives.”

| Treatment group | Overall survival | Progression-free survival |

| 177Lu-PSMA-617 + standard treatments | 15.3 months | 8.7 months |

| Standard treatments only | 11.3 months | 3.4 months |

Overall, serious side effects were limited among participants treated with 177Lu-PSMA-617. They included nausea and bone marrow effects, the latter of which led to approximately 13% of patients having to receive blood transfusions.

Another common side effect seen with the radiopharmaceutical was dry mouth, or xerostomia. Dry mouth is an expected side effect of 177Lu-PSMA-617 because the salivary glands are one of the normal tissues where PSMA tends to be produced.

Overall, 177Lu-PSMA-617 seems to be a relatively safe treatment, said Frank Lin, M.D., of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research, who is leading several small clinical trials of radiopharmaceuticals. But Dr. Lin noted some concern about the number of patients who had to receive blood transfusions and the five deaths attributed to the treatment.

Those numbers “are definitely higher than I would like,” Dr. Lin said. Nevertheless, the trial results “are good news overall,” he continued. “It’s always good to have more options for patients, especially those who have already received many treatments.”

Potential Accessibility Issues?

There are still some important questions to answer about 177Lu-PSMA-617, including possible hurdles to its use should it receive FDA approval, several researchers said.

One question is how to define whether a patient’s prostate cancer is PSMA positive. For the VISION trial, PSMA positivity was defined as having at least one metastatic tumor detected with PSMA PET imaging. Other trials, including a smaller trial of 177Lu-PSMA-617 conducted in Australia, have also used PSMA PET imaging, but had somewhat more stringent criteria for PSMA-positive disease.

Under the criteria used in VISION, approximately 87% of men who were screened to possibly participate in the trial were considered to have PSMA-positive disease. Such a high positivity rate “begs the question of whether the [PSMA PET] imaging requirement is needed” for men to receive 177Lu-PSMA-617, Dr. Taplin said during a discussion of the trial results at the ASCO meeting.

That’s an important consideration, Dr. Lin said. Although two radiotracers have been approved for PSMA PET imaging, the technology is still not widely available at hospitals across the United States, he explained.

In a statement, Novartis said the company anticipates “that some mention of the importance of PSMA-expressing disease” would be part of an FDA approval of the drug for treating prostate cancer. But the specifics of how PSMA status will be assessed, the company noted, “will be up to regulatory agencies.”

Another factor that could affect access to 177Lu-PSMA-617 is its radioactive component. Under federal regulations, administration of anything containing radioactive material must involve somebody with extensive training in handling such materials—typically staff from a hospital’s nuclear medicine or radiation oncology departments. And many smaller hospitals do not have that expertise in house.

So access issues are likely to be a problem, Dr. Taplin said, although they will be lessened “as centers build capacity to meet increased demand for radiopharmaceutical treatment.”

Dr. Lin agreed that any patient access issues will likely lessen over time. And based on the positive research results with PSMA PET imaging and PSMA-based radiopharmaceuticals, he continued, “there is a lot of support [in the medical community] for the PSMA agents.” That support “should make for a good environment for this agent to become successful.”

Ongoing and planned clinical trials are testing 177Lu-PSMA-617 in patients with earlier stages of prostate cancer, Dr. Morris said, as well as studies testing the drug in combination with other treatments, including targeted therapies like PARP inhibitors and immunotherapy.