, by Carmen Phillips

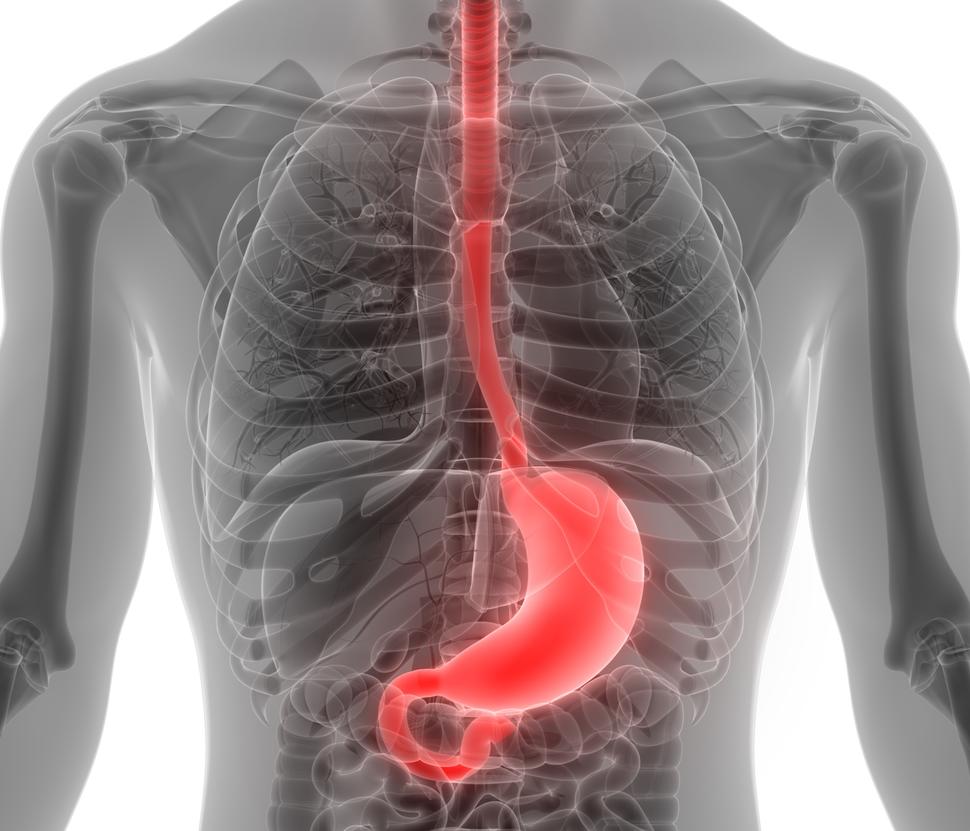

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has amended its 2021 accelerated approval of the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab (Keytruda) as part of treatment for some people with advanced stomach cancer and gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) cancer.

The initial approval covered the use of pembrolizumab along with trastuzumab (Herceptin) and chemotherapy for people with advanced HER2-positive stomach (or gastric) or GEJ cancer, meaning that their tumors produced high levels of the protein HER2.

Under the updated approval, announced on November 9, pembrolizumab can now only be used for people with these cancers whose tumors also have high levels of another protein, PD-L1. Levels of PD-L1 are determined using something called a combined positive score (CPS), and the amended approval is for people whose tumors have a PD-L1 CPS of 1 or greater.

The decision to change the initial approval was based on updated results from a large clinical trial, called KEYNOTE-811, which showed that pembrolizumb was effective only in participants whose tumors had elevated PD-L1 levels (PD-L1–positive). About 85% of the trial’s participants had PD-L1–positive tumors.

Although adding pembrolizumab to trastuzumab and chemotherapy improved how long patients lived without their disease getting worse, a measure known as progression-free survival, the improvement was driven solely by participants whose tumors were PD-L1–positive.

In fact, trial participants treated with pembrolizumab whose tumors had no or very little PD-L1 appeared to have worse outcomes than those treated with only trastuzumab and chemotherapy. The updated KEYNOTE-811 results were presented October 20 at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) annual meeting in Madrid and published the same day in The Lancet.

The findings represent the first meaningful improvements for people with HER2-positive stomach and GEJ cancer in more than a decade, said the trial’s lead investigator, Yelena Janjigian, M.D., from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York, at the ESMO meeting.

Seeing the survival improvements “is very satisfying,” Dr. Janjigian said. Adding pembrolizumab to trastuzumab and chemotherapy “will transform some patients’ lives,” she continued.

After HER2, the biology points to PD-L1

Although trastuzumab and other drugs that target HER2 are commonly used to treat breast cancer, over the past decade researchers have found that HER2 is elevated in other cancers as well, including stomach cancer and GEJ cancer (which develops at the junction where the esophagus meets the stomach). About 15% of people with advanced stomach cancer and 30% of people with advanced GEJ cancer have HER2-positive tumors.

In 2010, a large clinical trial showed that adding trastuzumab to chemotherapy substantially improved how long people with HER2-positive gastric or GEJ cancer lived—the first study in decades to show an improvement in survival in this cancer. It rapidly became the standard treatment for HER2-positive stomach and GEJ cancer.

Since then, there have been no real advances for treating HER2-positive forms of these cancers, Dr. Janjigian said at the ESMO meeting. But there have been advances in understanding their underlying biology, including how they develop resistance to HER2-targeted treatments.

For example, her group at MSKCC has shown that HER2-positive stomach and GEJ tumors, after prolonged attack by trastuzumab, begin to increase levels of several other proteins, including PD-L1. Part of a family of proteins called immune checkpoints, PD-L1’s primary role in tumors is to protect them from the immune system.

Pembrolizumab is from a family of drugs called immune checkpoint inhibitors. It works by disrupting PD-L1’s ability to block immune cells from attacking cancer cells. The apparent role of PD-L1 in stomach and GEJ cancer spurred the initial clinical trials testing pembrolizumab in people with these cancers, Dr. Janjigian explained.

Initial results from KEYNOTE-811, released several years ago, showed that tumors shrank—and sometimes disappeared entirely—in more than 70% of patients with advanced disease who received pembrolizumab in addition to trastuzumab and chemotherapy. Not long after, FDA announced its original accelerated approval.

PD-L1 levels makes the difference

The nearly 600 participants in KEYNOTE-811 were randomly assigned to receive trastuzumab and chemotherapy (most often a regimen called CAPOX) or to receive those treatments plus pembrolizumab. The majority were White, younger than age 65, male, and had stomach cancer. Merck, which manufactures pembrolizumab, funded the trial.

Based on the participant follow-up to date (a median of nearly 40 months), the improvement in median progression-free survival in the entire group that received pembrolizumab was modest. In participants whose tumors had high PD-L1 levels, however, the improvement with pembrolizumab was more robust. (See the table.)

In addition, although trial participants need to be followed longer to get greater statistical certainty, the findings thus far indicate that those who received pembrolizumab also lived longer overall.

| Outcome | Pembrolizumab + Trastuzumab + Chemo | Trastuzumab + Chemo |

|---|---|---|

| Progression-free survival (whole group) | 10.0 months | 8.1 months |

| Progression-free survival (PD-L1–positive) | 10.9 months | 7.3 months |

| Overall survival (whole group)* | 20.0 months | 16.8 months |

| Overall survival (PD-L1–positive)* | 20.0 months | 15.7 months |

* Overall survival analysis not yet final

The overall survival analysis is still not final, Dr. Janjigian noted. But for people whose tumors had high PD-L1 levels, the trend thus far is promising.

Among trial participants with low PD-L1 levels, by comparison, the most recent data showed that people in the pembrolizumab group had worse survival. The results in people with low PD-L1 levels strongly suggest that adding pembrolizumab may do more harm than good, said Florian Lordick, M.D., of the Leipzig University Cancer Center, in Germany, at the ESMO meeting.

“So don’t … give pembrolizumab to [HER2-positive] patients who are negative for PD-L1,” Dr. Lordick said.

Side effects seen with the addition of pembrolizumab were virtually the same as those usually seen with immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment, Dr. Janjigian said, including immune-related problems like inflammation in the lungs and colon.

Serious side effects were somewhat more common in the pembrolizumab group, and several patients in each treatment group died as a result of treatment-related side effects.

Changing patient care, looking for more answers

In an accompanying editorial in The Lancet, Elizabeth Smyth, M.D., of Cambridge University Hospitals in the United Kingdom and Raghav Sundar, M.D., Ph.D., of the National University Cancer Institute, Singapore, argued that, although the final overall survival results are not yet available, the results to date are convincing.

Overall survival in people whose tumors have high PD-L1 levels was not one of the trial’s primary measures, they acknowledged. But “the sample size [of PD-L1 high patients] and survival advantages are substantial enough to warrant a change in clinical practice for this subgroup of patients.”

Some attendees at the ESMO meeting asked whether drugs like pembrolizumab may be most effective in people whose tumors have even higher PD-L1 levels, as studies in other cancers have suggested. Dr. Janjigian noted that the research team is still analyzing that data in their trial.

Dr. Lodrick agreed that there’s a need for more precise biomarkers to identify patients who should and shouldn’t get pembrolizumab. Nevertheless, he said, a PD-L1 CPS of 1 or greater is “still a biomarker that we should use in this setting.”

Other research being conducted by Dr. Janjigian’s group, she said, suggests that a single marker, at least at a single moment in time or in a patient’s individual tumor, may not be the best way to identify who’s likely to benefit.

“It’s not as simple as just PD-L1 or HER2,” she said. “It’s a little bit more complicated. Stay tuned.”