June 7, 2019, by NCI Staff

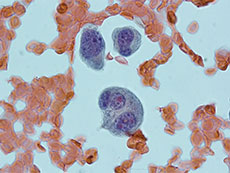

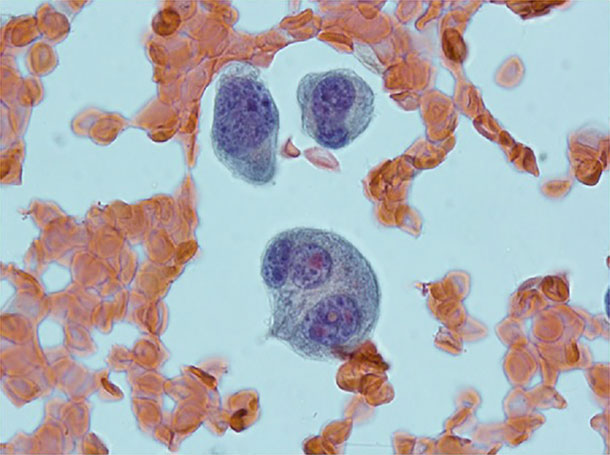

Smoldering myeloma is a slow-growing type of multiple myeloma, a form of cancer in which abnormal plasma cells (purple) make too much of a single type of antibody.

Credit: Case Rep Oncol Med. Nov. 2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/257814. CC BY 3.0 US.

The drug lenalidomide (Revlimid) may delay the development of multiple myeloma in individuals with smoldering myeloma that is at high risk of progressing to cancer, according to preliminary results from a clinical trial.

Smoldering myeloma is a precancerous condition that alters certain proteins in blood and/or increases plasma cells in bone marrow, but it does not cause symptoms of disease. About half of those diagnosed with the condition, however, will develop multiple myeloma within 5 years.

Because there are no approved treatments for smoldering myeloma, doctors have long adopted a “watch and wait” approach, closely monitoring individuals for evidence of progression to active (symptomatic) multiple myeloma, such as damage to certain organs.

But by the time symptoms of multiple myeloma appear, the disease may have caused painful and debilitating health problems, including bone fractures and kidney failure.

In the NCI-supported clinical trial, researchers found that lenalidomide—which is already used to treat multiple myeloma—may delay or slow the progression of smoldering myeloma.

Individuals who received the drug had a reduced risk of developing multiple myeloma within 3 years, compared with individuals who were observed for symptoms of cancer during the same period, according to Sagar Lonial, M.D., chief medical officer at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University, who led the trial.

More than half of the participants in the trial who were receiving the drug stopped taking it because of side effects, such as fatigue. In most of these patients, the side effects were treatable, noted Dr. Lonial.

He discussed the findings May 15 during a press briefing that featured studies to be presented at the upcoming annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) in Chicago.

The new results, together with findings from previous studies, point to the potential for using therapies like lenalidomide in individuals with smoldering myeloma who are at high risk of progressing to cancer, Dr. Lonial said.

Focusing More on Cancer Prevention

Researchers have long sought to identify individuals with smoldering myeloma who are at greatest risk of developing cancer and find ways to delay or even prevent this progression.

The development of drugs such as lenalidomide that have fewer side effects than chemotherapy has enabled researchers to test this strategy. Lenalidomide may enhance the ability of immune cells to kill abnormal cells that lead to multiple myeloma.

In 2013, Spanish researchers reported results from a clinical trial showing that the combination of lenalidomide and dexamethasone delayed the progression to multiple myeloma in individuals with smoldering myeloma who were at high risk of disease progression. Individuals who received the combination therapy also lived longer than those randomly assigned to observation.

In a follow-up study a few years later, the researchers noted that some individuals with high-risk smoldering myeloma may have weakened immune systems compared with healthy individuals. Furthermore, the researchers proposed, lenalidomide might help to “reactivate” certain immune cells that can kill any cells that become cancerous.

When a person is diagnosed with smoldering myeloma, doctors can assess various clinical factors, such as changes in blood proteins, to determine whether the person has a high, intermediate, or low risk of developing multiple myeloma within 2–3 years.

A goal of the new trial was to see whether lenalidomide, as a single agent, could help prevent the progression of smoldering myeloma to cancer—and the health problems associated with it—in patients at high risk of progressing in a relatively short period of time, according to Dr. Lonial.

“This study addresses an important question: Can we use new drugs to change the natural history of myeloma by treating patients earlier and thereby preventing myeloma-related damage to organs?” said Dickran Kazandjian, M.D., of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research, who studies multiple myeloma but was not involved in the trial.

Although more studies are needed to answer this question, he continued, the lenalidomide trial is an example of where research on smoldering myeloma is headed.

“Testing lenalidomide for smoldering myeloma is a step forward,” Dr. Kazandjian added. “However, the approach is not ready for prime time. It should not be the standard treatment in community settings, and patients should instead be referred to clinical trials.”

Testing Lenalidomide Alone

Dr. Lonial and his colleagues used imaging tools to make sure that participants in the trial did not have undiagnosed multiple myeloma at the time of enrollment. Once enrolled, participants were further classified as being at intermediate risk or high risk for progression to multiple myeloma.

The current study had two components. First, a phase 2 trial evaluated the safety and effectiveness of lenalidomide in 44 patients with smoldering myeloma. That study showed the treatment was safe and may slow the progression of smoldering myeloma in some individuals.

Next, the researchers conducted a phase 3 trial. They randomly assigned 182 individuals with smoldering myeloma to receive the drug or undergo careful observation.

After 3 years, smoldering myeloma had not progressed to multiple myeloma in 91% of patients receiving lenalidomide, compared with 66% of people who did not receive the drug and were observed for signs of progression to cancer, according to results from the randomized phase 3 trial.

In the phase 2 study, 78% of the group had not experienced progression to myeloma after a median follow-up of more than 5 years, said Dr. Lonial. Based on previous studies, one would expect that about 50% to 60% of the patients would have developed multiple myeloma in that time frame, he noted.

“These results suggest that we have prevented the development of organ damage and symptomatic myeloma in a large fraction of patients,” said Dr. Lonial.

Dr. Kazandjian cautioned, however, that longer follow-up “is needed before we can draw conclusions about this treatment approach for patients.” One of the unanswered questions, he noted, is whether individuals who receive lenalidomide will live longer than those who do not receive this drug.

Side effects, such as fatigue and neutropenia, led many participants to stop taking the drug, including 80% of those in the phase 2 study and 51% of individuals in the phase 3 study.

Dr. Lonial noted, however, that the side effects in most patients were reversible.

The fact that some participants stopped taking lenalidomide early due to side effects has allowed the researchers to assess whether less than a full course of treatment might benefit some patients.

Preliminary results suggest the answer might be yes. Patients who stopped taking the drug “didn’t immediately progress, suggesting that the drug’s effects on the immune system may continue even after patients have stopping using the drug,” Dr. Lonial said.

Future Research

More research is needed to identify additional risk factors that may predict whether a patient is likely to progress sooner rather than later.

In this trial, both intermediate-risk and high-risk groups “appeared to benefit from early intervention,” said Dr. Lonial, noting that future studies can explore the potential benefits of drugs such as lenalidomide for patients with intermediate-risk smoldering myeloma.

“When you put the results of our trial together with the results of the Spanish trial, I think that many of us would argue that early intervention with a prevention strategy can reduce the risk of progression to symptomatic myeloma,” he went on.

Dr. Kazandjian agreed. “In the near future, doctors may use drugs to try to prevent the progression of smoldering myeloma to cancer,” he said, noting that three-drug combinations might be more effective than single agents.

Three-drug combinations, or triplets, have been more effective than single agents or two-drug combinations in treating patients with multiple myeloma, added Dr. Kazandjian. He expects to learn more about this approach from an NCI-supported clinical trial testing the triplet of carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone in patients with smoldering myeloma.

Dr. Lonial noted that another NCI-supported clinical trial could also provide useful information. The study is testing lenalidomide and dexamethasone with or without daratumumab for high-risk smoldering myeloma.