June 17, 2019, by NCI Staff

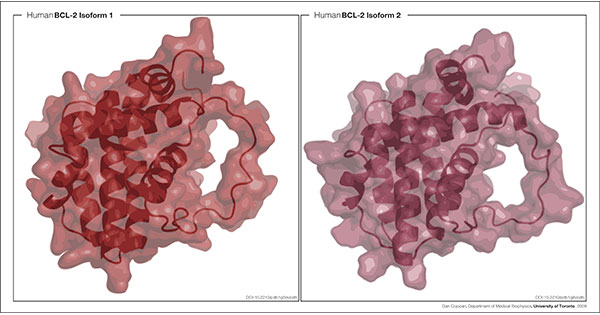

The drug venetoclax works by blocking the action of the BCL2 protein, depicted here.

Credit: Dan Cojocari, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University of Toronto. CC BY 3.0.

Additional coverage: A new study shows that combining venetoclax (Venclexta) with ibrutinib (Imbruvica) may be an effective initial treatment for CLL.

On May 15, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved venetoclax (Venclexta) in combination with obinutuzumab (Gazyva) for the initial treatment of adults with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL).

“This is the second chemotherapy-free regimen now approved for first-line treatment of CLL, and the first such regimen that is given for a limited duration,” said Milos Miljković, M.D., who studies CLL in NCI’s Center for Cancer Research. The combination of venetoclax and obinutuzumab is given in 12 four-week cycles.

The other FDA-approved treatment for CLL and SLL that does not involve chemotherapy is ibrutinib (Imbruvica). Patients receiving this drug take it until the disease progresses or the side effects become unmanageable.

Both CLL and SLL grow slowly. In CLL, the bone marrow makes too many lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell); in SLL, the lymph nodes produce too many lymphocytes.

Venetoclax, a pill, blocks the action of a protein called BCL2, which helps to keep cancer cells alive. Obinutuzumab, a monoclonal antibody that is injected intravenously, targets a protein called CD20, which is frequently found on the surface of tumor cells in patients with certain types of leukemias.

Venetoclax was initially approved by FDA in 2016 to treat individuals with CLL that has a specific genetic alteration, called deletion 17p. In 2018, the agency expanded the drug’s approval to include individuals whose cancers have progressed after receiving at least one previous treatment, regardless of whether their cancer cells have the genetic change.

FDA’s new approval was based on the results of a phase 3 clinical trial comparing the effectiveness and safety of venetoclax in combination with obinutuzumab versus obinutuzumab plus the chemotherapy drug chlorambucil in individuals with CLL or SLL and coexisting medical conditions.

Results from the clinical trial, which was supported by the makers of venetoclax, F. Hoffmann–La Roche and AbbVie, were published in the New England Journal of Medicine on June 6.

Participants who received venetoclax plus obinutuzumab were 67% less likely to have the disease worsen or to die than those who received chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab. The overall response rate was 85% in the venetoclax-plus-obinutuzumab group and 71% in the chlorambucil-plus-obinutuzumab group.

“Neither group had high rates of disease progression or death,” said Dr. Miljković, who was not involved in the trial. More than half of the participants in each group were still alive without the disease worsening at a median follow-up of 28 months after the start of treatment.

The most common side effects among patients in the venetoclax group included low white blood cell count, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, low red blood cell count, and upper respiratory tract infection.

The combination therapy used as a comparison in the trial—obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil—is approved for patients with untreated CLL, but the treatment is rarely used, according to Dr. Miljković.

“A more relevant comparison in the trial would have been between the venetoclax–obinutuzumab combination and ibrutinib,” Dr. Miljković said. Without a study directly comparing these treatments, he predicted that doctors will select treatments based largely on factors such as patient preference and additional health conditions.

For patients, he went on, the choice may come down to whether they prefer a time-limited treatment with obinutuzumab and venetoclax that requires visits to a doctor’s office or clinic or a “straightforward but indefinite treatment with ibrutinib.”

Trial Tests Ibrutinib and Venetoclax Combo in CLL

For some people newly diagnosed with CLL, a combination of ibrutinib and venetoclax has shown promise as an initial treatment for the disease, according to the results of a study at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

The phase 2 clinical trial included 80 previously untreated patients with CLL, most of whom had genetic alterations that put them at high risk of the disease worsening. All participants in the study received the combination therapy (there was no control group).

After a median follow-up of nearly 15 months, 88% of patients had complete remissions, and 61% of patients had complete remissions with no detectable CLL in the bone marrow, according to results published May 30 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“We’re very excited about the responses we’ve seen in patients receiving this combination,” said William Wierda, M.D., Ph.D., who led the study.

“This was a well-tolerated, fixed-duration treatment regimen,” Dr. Wierda continued. “The combination therapy did not increase side effects beyond what is usually seen when these drugs are given as single agents,” he added.

The results compare favorably with previous studies evaluating ibrutinib alone or venetoclax-based therapy for CLL. In those studies, many patients had partial responses, and few patients experienced remissions with no detectable CLL in bone marrow, according to the researchers.

The results are “impressive” for several reasons, wrote Adrian Wiestner, M.D., Ph.D., who studies CLL at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, in an accompanying editorial.

“First, every patient had a response, almost all had a complete response, and in most no residual disease was detected,” Dr. Wiestner continued. “Second, there appears to be no added toxicity from combining the two drugs.”

The treatment regimen included a period in which participants received ibrutinib alone prior to starting venetoclax. Ibrutinib may reduce the size of the tumor and the risk of a side effect seen with venetoclax known as tumor lysis syndrome.

The median follow-up time was less than the duration of treatment itself, which is 2 years, noted Dr. Miljković. “It is therefore unclear whether these responses will be lasting, particularly after the end of treatment,” he said.

Another open question, Dr. Miljković continued, is whether initially combining the treatments would be more effective than giving one drug first for a period, followed by the other.