, by NCI Staff

Until about 10 years ago, most men diagnosed with prostate cancer that has a low risk of causing death had immediate treatment with surgery or radiation. Although both are considered to be cures for low-risk prostate cancer, they can also have serious and lifelong side effects, including urinary problems and erectile dysfunction.

But a recent study confirms findings from earlier studies that found men are increasingly opting against immediate treatment. Instead, they are working with their doctors to carefully monitor the cancer via a process known as active surveillance, holding off on treatment until there are signs of progression.

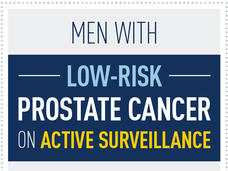

Overall, the study, which included data from 240 urology practices across the country, found that about 60% of US men diagnosed with low-risk prostate cancer are now being managed with active surveillance. In fact, the rates of active surveillance more than doubled between 2014 and 2021, the time period covered by the study.

The finding is encouraging and shows that the use of active surveillance is “headed in the right direction,” said the study’s lead investigator, Matt Cooperberg, M.D., of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), who reported the findings on May 15 at the American Urological Association’s (AUA) 2022 annual meeting. “But they are still not where they need to be.”

Of particular concern, Dr. Cooperberg noted, is the finding that in some urology practices only a small percentage of patients with low-risk prostate cancer are on active surveillance. There were urologists in some practices who did not have a single patient with low-risk disease on active surveillance.

Those findings fly in the face of recommendations from leading medical groups that say active surveillance is the preferred approach for men diagnosed with low-risk prostate cancer.

“Those [doctors] are doing their patients a disservice,” said Howard Parnes, M.D., chief of the Prostate and Urologic Cancer Research Group in NCI’s Division of Cancer Prevention, who was not involved in the study. “If a patient meets the criteria for low-risk disease, active surveillance needs to be a central part of the conversation.”

Reconsidering immediate treatment

Most prostate cancers diagnosed with PSA-based screening, which became widespread in the United States starting in the early 1990s, are low-risk. Generally speaking, that means they are small, confined to the prostate, and not considered to be aggressive according to a common grading system known as the Gleason score.

Nevertheless, throughout the 1990s and well into the 2010s, many men diagnosed with low-risk prostate cancer had immediate treatment with surgery or radiation.

According to the most recent guidelines from the AUA and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), low-risk prostate cancers are those that meet these criteria:

- PSA level of less than 10

- Gleason grade group 1 (Gleason score 3 + 3)

- Clinical stage T1‒T2a

Learn more about PSA testing, Gleason grade groups, and clinical staging.

(NCCN also has a very-low-risk category, for which active surveillance is also recommended.)

But even in the early days of widespread PSA screening, questions were raised about whether these “screen-detected” cancers were actually dangerous. Studies followed that echoed those concerns, concluding that many of these cancers would likely never grow to the point where they would even cause symptoms, let alone become life-threatening.

Another alternative to immediate treatment is “watchful waiting,” simply waiting for symptoms before pursuing any further testing or treatment.

But because prostate cancer can be deadly once it spreads beyond the prostate, use of watchful waiting in men with low-risk prostate cancer has been limited.

Protocols for active surveillance were first proposed in the mid-1990s and have since been studied and implemented in various forms. It’s only fairly recently that leading medical organizations felt the data on the safety of active surveillance were strong enough to formally recommend it as the preferred approach for men with low-risk disease.

How is active surveillance done?

Although the protocol can vary, recommendations for active surveillance generally call for routine PSA tests and prostate biopsies to check for any indication that the cancer might be growing.

For example, patients at Montefiore Health System in New York City get a PSA test every 3‒6 months, at least initially, and an MRI-guided biopsy a year after diagnosis, said Kara Watts, M.D., a urologist at the hospital who specializes in treating prostate cancer but was not involved in the study.

After the initial PSA tests and biopsy, how often they are performed depends largely on the patient’s particular situation, Dr. Watts explained.

“We have a flexible protocol, particularly for people at both ends of the [age] spectrum,” she continued. For a man in his 70s and a life expectancy of 5‒10 years (based on other health conditions and other factors), she said, additional PSA tests or biopsies may only be conducted every few years or only if he has symptoms. An otherwise healthy man in his 50s, on the other hand, will usually continue to have PSA tests and MRI-guided biopsies on a schedule similar to the initial protocol.

At the NIH Clinical Center, where Dr. Parnes sees patients, in addition to routine PSA testing, MRI-guided biopsies are used to help inform decisions around whether to pursue active surveillance and as part of the surveillance protocol.

“MRI-guided biopsies have been shown to improve the detection of intermediate- and high-grade prostate cancer, but they aren’t required for active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer,” Dr. Parnes explained. “Many studies using standard ultrasound-guided biopsies have demonstrated the long-term safety of active surveillance in men with low-risk prostate cancer,” he said.

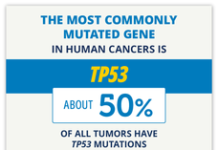

Genetic and molecular testing are also making their way into doctors’ decisions to recommend active surveillance and as part of the surveillance protocol. At NCI, for example, men with a family history of cancer or who are diagnosed with intermediate-risk prostate cancer are recommended to undergo testing for mutations in the BRCA2 gene or other genes involved repairing damaged DNA, Dr. Parnes said.

Finally, regardless of the doctor or hospital where a patient is being treated, if biopsy results suggest that the cancer grade is progressing, men will generally be advised to receive immediate treatment. The number of men on active surveillance who eventually get treated with surgery or radiation varies. In a recent, large observational study involving over 8,000 men, just under half of those on active surveillance received definitive treatment within 5 years.

More active surveillance, but not enough

To conduct their study, Dr. Cooperberg and his colleagues looked at data from all men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer in the AUA Quality Registry. This registry collects real-time data from more than 240 participating US urology practices and more than 2,100 urologists.

Overall, of the more than 84,000 patients covered by the study, 20.3% were diagnosed with low-risk disease. The number of men diagnosed with low-risk disease actually fell during the study period, from about 24.6% in 2014 to 14.0% in 2019. That finding is consistent with other recent studies showing a decline in low-risk diagnoses, which researchers have attributed to fewer men being screened via PSA testing.

But even as diagnoses of low-risk disease have dropped, more men with low-risk disease are opting for active surveillance, Dr. Cooperberg reported. In 2014, 26.5% of men with low-risk prostate cancer chose active surveillance. By the end of 2021, 59.6% did.

Rates of active surveillance also increased among men diagnosed with intermediate-risk prostate cancer, which is considered to have a modestly greater likelihood than low-risk prostate cancer of progressing to the point where it could be fatal.

The steady uptick is welcome news, Dr. Cooperberg said. But he also highlighted the “relatively extreme” variation in the use of active surveillance across the country. The researchers found that rates of active surveillance for men with low-risk prostate cancer “can range from 7% to nearly 80%” by urology practice, he said. “And, depending on which individual doctor’s door you knock on, even within a given practice, rates range from 0% to 100%.”

The variability in the use of active surveillance is alarming, Dr. Parnes said. It likely reflects, at least to some degree, entrenched patterns of care among some urologists. “For some, I suspect their feeling is, ‘I treat cancer, and this is cancer. I’m not having this conversation [about active surveillance],’” he said.

Dr. Watts agreed. It’s likely that some doctors “just aren’t discussing [active surveillance], or they’re portraying it in a way that biases [patients] toward definitive treatment,” she said.

Exceptions and barriers to active surveillance

In his UCSF program, Dr. Cooperberg said, about 95% of men diagnosed with low-risk prostate cancer are put on active surveillance. As an academic center that began implementing and studying active surveillance in the mid-1990s, that’s likely higher than what is typically seen in the United States, he acknowledged.

But a “reasonable target” for the time being is around 80%, he said. That’s consistent with where rates “top out” in countries like Sweden and in other large, integrated health care systems in Europe where active surveillance has long been standard practice.

The bottom line, Dr. Cooperberg said, is that even though the vast majority of men with low-risk prostate cancer should be put on active surveillance, “there will always be exceptions.”

Those exceptions, for example, can include men with a strong family history of prostate cancer or who have urological symptoms related to the disease that immediate treatment can help to alleviate.

There can also be considerations that go beyond clinical or biological factors. For patients in rural areas or those who lack reliable transportation, anything that requires regular visits to the hospital or doctor’s office over a long period could push some men toward choosing immediate treatment, Dr. Watts said.

In addition, she noted, it can be challenging to explain the medical basis for active surveillance. In some patient’s minds, opting for active surveillance means “missing a window of opportunity for cure,” she said.

“The ‘C word’ is scary for a lot of people,” Dr. Watts continued. And in this case, “a lot of the art of medicine is being able to explain … why active surveillance is appropriate.”