We’ve all seen the headlines.

Whether it’s ‘Waiting lists for cancer treatment soar’ in the Express, the Mail talking about ‘Record NHS waiting lists’ or the Guardian reporting ‘Waiting times for cancer care in England longest on record’, the pressure on NHS cancer services is hard to miss.

But why are cancer waiting times so important? And, looking beyond the news stories, what do they mean for people affected by cancer?

Setting a target

Cancer waiting times are a way to look at how well NHS cancer services are performing. They outline the maximum time most patients should expect to wait for cancer diagnosis and treatment and come with an associated set of targets.

They’re important because waiting for results, or to start cancer treatment, is a stressful and anxious time for patients and their families. Not only this, but cancer that’s diagnosed and treated at an early stage, when it isn’t too large and hasn’t spread, is more likely to be treated successfully. Prompt diagnosis and treatment underpin this.

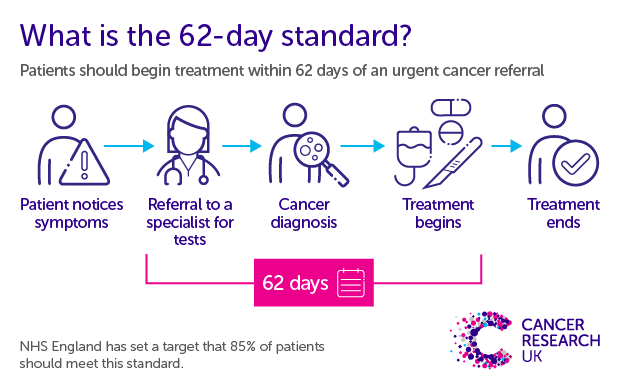

One important cancer waiting time target in England is the 62-day target. This advises that 85% of patients should begin treatment within 62 days (2 months) of an urgent suspected cancer referral.

What’s been happening to waiting times?

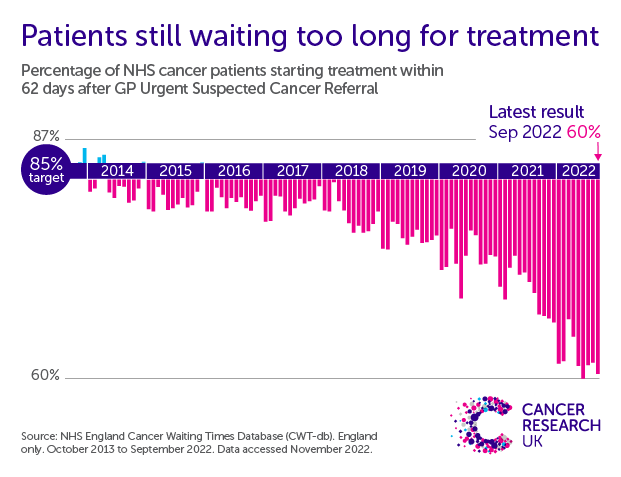

In the most recent data for England, for September 2022, the NHS only met the 62-day standard for 60% of patients, well below the target of 85%, and the second worst performance on record. That means that around 6,000 people who started cancer treatment in September waited longer than 62 days.

And when was the last time the target was met?

December 2015. Nearly seven years ago.

Performance was declining even before COVID, but the pandemic saw things quickly get even worse. This is not a crisis brought on by COVID, but it has been accelerated by the pandemic.

Even more shockingly, for some specific cancer sites, performance is particularly poor. For example, for lower gastrointestinal (GI) cancers, less than 40% of patients start their treatment within 2 months of their urgent referral.

Why is performance declining?

We spoke to Professor Michael Lind, a consultant oncologist based in Hull, and Professor Chris Cunningham, a consultant colorectal surgeon in Oxford, to understand more about what is driving these trends.

They told us there are many reasons behind the decline, but pressure on diagnostic services, such as radiology, is a major factor.

Cunningham explains: “It’s not just access to diagnostic services, but access to getting an appropriate opinion and a report from that in a timely fashion.”

And it’s not just radiology causing a bottleneck. From staff to do scans and biopsies, to pathologists with the skills to review blood samples and cells, from doctors who can manage patients to teams who handle the admin – the NHS is short of people. “There are major staffing issues in the medical and healthcare professions, including fewer oncologists than there were,” Lind says.

Meanwhile, an ageing and growing population means the number of people being referred for cancer investigations is increasing. So, despite the tireless work of NHS staff, they are facing an ever-growing challenge. There are more people to diagnose and treat than ever before, and the NHS needs more staff to keep up.

“The whole system is more sophisticated now. There is much more we need to know about our patients and there are many more tests to do,” Lind says.

The rise of long-waiters

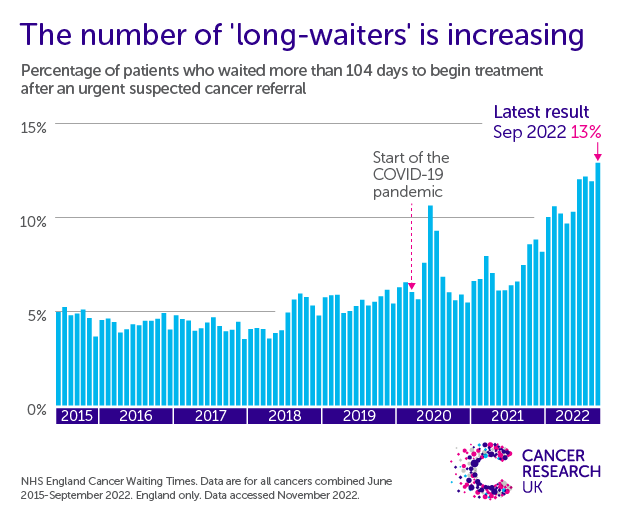

Some people face extremely long waits to get diagnosed and begin treatment after referral.

These ‘long waiters’ are people who wait more than 104 days (that’s nearly 3 and a half months) to begin treatment after an urgent referral. There is no official target related to long-waiters, but generally waits of this length of time should not occur. This is why clinicians have to review all cases where this happens, to see whether there were any avoidable delays.

Worryingly, we’re seeing an increase in the number of long-waiters.

Before 2018, the number of long waiters was quite stable at less than 5% of people diagnosed after an urgent referral. But then this started to creep higher. Since 2020, the numbers have increased even more rapidly. We’re now seeing the highest levels of long waiters on record.

In September 2022, more than 1 in 10 (13%) patients waited more than 104 days from their urgent referral to begin treatment. More than 10,000 people in the last six months have been long-waiters, which is more than triple the number from the same months in 2017. For a country that aims to lead the world in cancer care, this is unacceptable.

The picture varies across cancer types. Some types of cancers which can be difficult to diagnose, or which are facing particularly harsh pressures, are showing even more concerning trends. For example, in the most recent data for lower GI cancers, more than 2 in 10 (21%) people diagnosed with cancer after an urgent suspected cancer referral were long-waiters.

“It’s been really tough over the COVID period because there’s lots more short-term rearrangement of appointments – patients are cancelling or staff are ill,” says Cunningham. “I sense that there’s a bit of a tipping point with pathways and infrastructure and admin particularly, where things just become overwhelmed.”

Lind explained that the team of health professionals that plans treatments for people with cancer sometimes needs more information before making a decision about what course of action is best. That might mean requesting more tests or scans. This back and forth between different teams takes time and delays for tests can add up. “Getting reports and scans for things is becoming a real issue,” says Lind, “Sometimes it can take several months.”

Pressure on diagnostic services is playing an important role in both 62-day target performance and the rise of long-waiters. And if people are waiting longer for a diagnosis or decision on what treatment is needed, they’re waiting longer to start that treatment, too.

What do long waiting times mean for people affected by cancer?

People affected by cancer have rightly expressed concern about cancer waiting times. In the 2021 Cancer Patient Experience Survey, the length of time taken to start treatment was the most common issue highlighted in interviews. Some people were concerned these delays could impact their prognosis.

“Patients feel like they are sitting on a time bomb. Waiting to do things is very difficult,” says Lind.

“It’s a stress for them and a stress for their families,” Cunningham agrees. While he himself hasn’t seen cases where he believes a delay has caused harm, long waits could lead to more aggressive cancers growing or a decline in patient health. “There might be real harm because cancer has got to spread at some point. If your cancer is there for 104 days instead of 62, there will be some patients whose disease progresses to some extent.”

Quantifying the impact of these delays on patient outcomes is difficult as the research is limited. The picture is different for different cancer types – some progress quicker than others – but we know the impact is likely to be negative. One study estimated that a 4-week delay to cancer surgery led to a 6-8% increased risk of dying.

Patients with more aggressive cancers are prioritised for early treatment where possible, but there can be good reasons why someone might experience a long wait for treatment. For example, it can take longer to plan treatments intending to cure someone’s cancer, and sometimes patients need prehabilitation before starting treatment to give them the best chance of recovering well. But big increases in long-waiters means people who need potentially lifesaving cancer treatments are waiting, and worrying, for longer – and that is a big concern.

Clinicians are keen to stress that delays shouldn’t stop people coming forward if they are worried about symptoms. Lind is a lung cancer clinician and he still wants people to talk to their doctor if something doesn’t feel right for them. “If we’ve got a patient who we think may have lung cancer, are going to push things through as quickly as possible”

How do we get back on track?

The clinicians we spoke to were clear that the current situation cannot continue.

“I think a lot of people in the NHS are feeling quite demoralised and don’t see it getting any better. People feel like it’s a brick wall ahead.” Lind says.

“We can’t deliver everything we’re asked to deliver,” Cunningham explains. “Something is going to give.”

The poor performance and long waits that we’re seeing are a reflection of the increasing strain on NHS cancer services. They need more people, more equipment and more resources to cope with the growing demand.

The UK Government has an opportunity to deliver this in their new 10 Year Plan for Cancer. The new government could help take cancer outcomes in England from world lagging to world leading. But if cancer waiting time targets are to meaningfully contribute to the vision to improve cancer outcomes, then the Government must ensure this plan is ambitious, comprehensive and backed up by vital funding. Crucially, that plan has to address the workforce crisis that is contributing to growing waits.

That is the long-term solution to getting people the cancer services they deserve.