Our Science Surgery series answers your cancer questions.

Dr Francis Mussai, a Cancer Research UK-funded children’s cancer researcher and consultant oncologist at the Birmingham Children’s Hospital, says that the types of cancers that we see in children are very different to the cancer that we see in adults. “Cancer types that we frequently hear about in adults, such as breast, prostate, bowel, melanoma and lung cancer, are extremely rare in children.

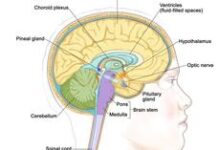

“Instead, it’s more common to see leukaemia’s, brain cancers, and cancers in developing structures, like muscle, nerve tissue and kidney,” Mussai explains.

But that’s not to say that children’s cancers themselves are common. Thankfully, the number of cancer cases in children and young people (aged 0-24) make up less than 1% of the total number of cancer cases diagnosed each year in the UK.

In children, leukaemia is the most commonly diagnosed cancer, accounting for almost a third of all cases in Great Britain. Brain and other central nervous system and intracranial tumours account for more than a quarter of all children’s cancers and lymphomas (a type of blood cancer) around a tenth. But it’s not just the types of cancers that differ, it’s also the biology.

Copy this link and share our graphic. Credit: Cancer Research UK.

Why do children get cancer?

“Adult cancers, on the whole, develop because of some sort of wear and tear or due to impacts of our lifestyle,” says Mussai, “which damage our DNA, and leads to a cell becoming abnormal and cancerous.”

The biggest cancer risk factor in adults is age. The older someone is, the more their cells will have divided, increasing the chances that DNA errors will occur. And as life goes on, people are also exposed to other factors that can damage their DNA – like alcohol, tobacco smoke and excess body weight.

Understanding why children get cancer is a huge task and extremely complex. Generally, the cause of these changes to DNA that can result in childhood cancers are unknown, but many are likely to arise as a single random event that takes place inside a growing cell, without having an outside, or environmental source. And because of this, there is sadly no successful way to prevent childhood cancers from happening.

Mussai explains, “research points to cancers in children developing from DNA errors that have occurred either during development in the womb, or because of infection or inflammation in early life leads to a second level of damage in the cells, which may cause cells to become abnormal and trigger the cancer process.”

Awareness is key

It’s not just the biology of the cancer that is different, but different circumstances mean that adults and children can be diagnosed in different ways.

Mussai explains how there’s a lack of awareness of children’s cancers, particularly with symptoms. With 1 in 2 adults getting cancer in their lifetime, “people are aware that cancer as an adult is possible and often know what the associated symptoms are. If an adult has an abnormal lump or coloration on the skin, they will, hopefully, seek their GP’s attention,” says Mussai.

But children’s cancers are very rare diseases. “People aren’t usually aware that symptoms in a child such as a lump, headaches, or bone pain could be cancer.” More often than not it isn’t, but it can affect how people initially go hospital.

Mussai explains that young children might not be able to clearly articulate their symptoms, such as a lump or pain. This means a child’s diagnosis can often be discovered by accident, “such as when a child’s being washed or when they fall over in a game of football and get an X ray”.

Teenagers and young adults have different challenges. “They often have fears about what they have found. A lump might be something bad and this leads to difficulties in communicating something may be wrong to their parents or GP.”

A different and dedicated approach

From the first conversations between a doctor and patient, caring for children with cancer needs a different and dedicated approach.

“With an adult, when we make the diagnosis, we have a detailed discussion with the patient around what a specific treatment entails, what the chances are of getting better and what the side effects are,” says Mussai. “The adult can then make a conscious decision about whether they really want that therapy or not. A young child can’t say, I don’t want treatment A or treatment B.

“The golden outcome, of course, whether you’re treating an adult or a child with cancer is for the cancer to be cured,” explains Mussai. “But for children, we are acutely aware we are trying to achieve a truly long-term cure so that that a child can grow up to be an adult and live 30, 40, 50 years or longer.”

This difference creates a different set of challenges for doctors in creating new treatments for children.

“When drugs are approved for adults with cancer, the benefit can be sometimes marginal in terms of overall survival. And that is a success. But in children, we need a much longer success. We need, years, decades.”

Life after cancer

Today, more children and young people are surviving cancer than ever before, with 8 in 10 children living for 5 years or more after their cancer diagnosis.

There’s a lot to celebrate. Since the 1950s, pioneering children’s cancer specialists have made fantastic strides in improving the outlook for children with cancer. “We would say that the majority of childhood cancers can be cured,” says Mussai.

“In the 1950s, almost everyone with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia died from it. Now, over 90% of patients are cured.”

But for these children, there needs to be an emphasis on life after cancer. And we know that survivors can experience serious long-term side effects.

“People forget the price for the patients that survive,” says Mussai. We’ve blogged before about the side effects of children’s cancer treatments, which can include heart conditions or effects on their growth.

And while 8 in 10 children surviving their cancer for more than 5 years represents huge progress, it’s not good enough. That’s where research comes in.

The journey doesn’t end there

There’s a lot of work still to be done to increase our understanding of children’s cancers. “By understanding the biology better, we will be able to design better treatment approaches that lead to really good long–term outcomes with low toxicity for our young patients.,” says Mussai.

“And that underlies everything that we’re really trying to do”.

We’re dedicated to raising awareness of childhood cancers and to developing a strong, long-lasting community of doctors, nurses and scientists to develop new treatments for children and young people with cancer.

“Showing that cancer in children exists is important, although they’re rare, all of us may know a family who has been affected by childhood cancers,” Mussai concludes.

Sheona Scales is Cancer Research UK’s paediatric lead