, by NCI Staff

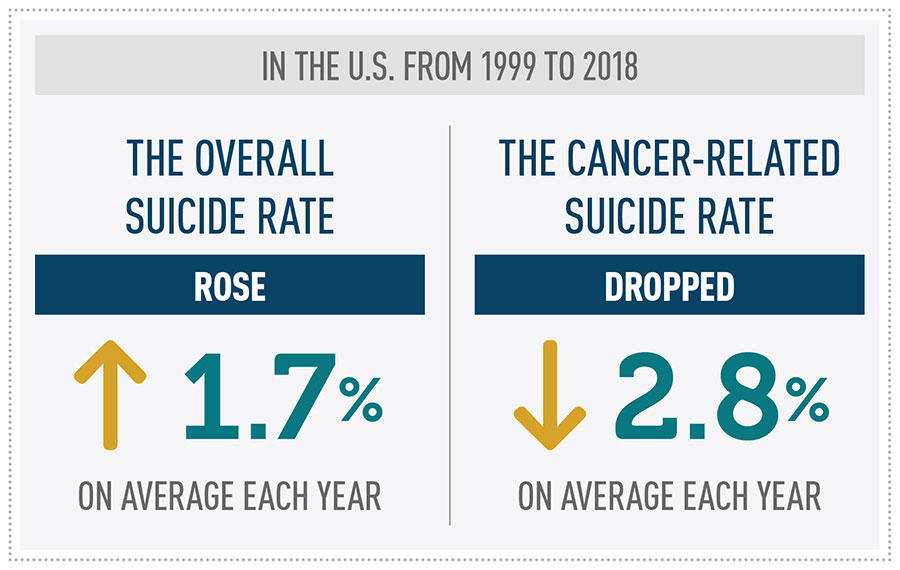

Over the last 2 decades, the suicide rate in the United States has been on a grim, steady march upwards. But a new study highlights an encouraging exception: between 1999 and 2018, the rate of suicide related to cancer decreased.

This drop was greatest among people considered to be at higher suicide risk in general, including men and older adults.

The findings were published January 19 in JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

People with cancer and those who have completed treatment can face a range of daunting challenges, said Emily Tonorezos, M.D., M.P.H., of NCI’s Office of Cancer Survivorship, who was not involved with the study. These can include pain from the cancer, disabling side effects of treatment, and financial distress.

“But we know that there have been tremendous advances in palliative and supportive care, in hospice, in providing mental health care, and in making it easier for survivors to access those types of resources,” Dr. Tonorezos said.

Supportive care is care given to improve the quality of life of patients who have a serious or life-threatening disease. Its goal is to prevent or treat as early as possible the symptoms of a disease, side effects caused by treatment of a disease, and related psychological, social, and spiritual issues.

The new study could not directly link improvements in supportive care to the reduced cancer-related suicide rate, “but this reduction represents something really positive for cancer survivors,” Dr. Tonorezos said.

Better mental health care, palliative care, hospice care, and symptom management for cancer patients and survivors all have the potential to reduce the risk of suicide, explained Xuesong Han, Ph.D., of the American Cancer Society, who led the research. “That’s what motivated us to examine the trends in cancer-related suicide,” she said.

Improvements across Populations

Dr. Han and her colleagues used death certificate data collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention between 1999 and 2018. Among deaths recorded as suicides, a subset were coded as cancer-related suicides. These could have been among either people undergoing cancer treatment or those who had completed treatment, Dr. Han explained.

As seen in previous studies, the overall suicide rate across the United States rose during those 2 decades, by an average of 1.7% a year. But over the same period, cancer-related suicides dipped, by about 2.8% each year. In addition to the large declines among people aged 65 and over and men, substantial drops in such suicides were seen among people in the southern and northeastern United States, in urban areas, and among people with prostate or lung cancers.

However, prostate and lung cancer, as well as colorectal cancer, were still the most common cancers among people who died by suicide. As well as being some of the most common cancer types, “symptoms of these cancers tend to be harsh, and can have a large impact on [that person’s] quality of life,” said Dr. Han.

These three cancer types can also overlap with other risk factors for suicide, she added. For example, gender: Men are at higher risk of suicide overall, and prostate cancer occurs exclusively in men. Men make up a greater proportion of lung cancer patients as well. And people with some pre-existing mental health conditions that increase suicide risk, including depression, are more likely to smoke—the leading cause of lung cancer, she explained.

More Room for Improvement

The sobering flip side of the encouraging decreases seen in the study is that “rates of suicide among cancer patients continue to be higher than [among] the general population, highlighting cancer patients as an at-risk group,” wrote a team led by Tessa Flores, M.D., of Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, in an accompanying editorial.

“Cancer patients experience depression at higher rates than the general population and report high levels of sleep disturbance, post-traumatic stress, anxiety, fear, and worry,” they wrote. These conditions “can get carried” forward beyond the completion of treatment, they explained.

Despite improvements in supportive care, people living with cancer can still be negatively affected by broader trends in health care. For example, efforts to contain the opioid epidemic may be playing a role in declining access to pain medication for patients with cancer. Although doctors are usually very willing to prescribe opioids to help treat cancer-related pain, Dr. Tonorezos noted, cancer patients can be affected by opioid restrictions.

“For example, they may not be able to use a local pharmacy because the pharmacy doesn’t stock the drugs or at the quantities that they need,” she said.

The cost of cancer care can also put immense stress on patients and their families. “It can be catastrophic to go through cancer treatment from a financial perspective,” Dr. Tonorezos continued. This burden now even has its own name: financial toxicity.

“It’s not just medical expenses,” she said. Costs of caregiving, transportation, supplies, childcare, and more can add up, she explained. Financial hardship from cancer treatment has been shown to impact people under the age of 65 in particular.

Reaching More People in Need

The need to comprehensively screen for depression in people with cancer has come into greater focus in recent years. For example, in 2015 the Commission on Cancer, a consortium of cancer-related professional organizations, began directing accredited cancer centers to screen patients for depression and distress.

But screening for depression in cancer patients and survivors can be easier said than done, said Gurvaneet Randhawa, M.D., of NCI’s Healthcare Delivery Research Program, who was not involved with the study. “Everyone wants to get it done. But despite all the good intentions, despite all the alignment of policies and guidelines and evidence, we still have bottlenecks that hinder the diagnosis and treatment of depression in cancer patients,” Dr. Randhawa said.

The bottlenecks can include lack of coordination between oncologists, mental health professionals, and other members of the cancer care team, a shortage of mental health professionals, and lack of follow-up with patients who report depression, he explained.

“The challenge in depression screening is not that we don’t have good instruments to screen and diagnose depression, or that we don’t have good treatments for depression. The challenge is doing [all this] systematically,” he said.

NCI is currently funding research teams who are developing information technology solutions to better integrate screening and treatment for depression into oncology practices.

“If we manage depression better, we should hopefully see an even bigger impact on suicide,” said Dr. Randhawa.

More research is also needed to better target cancer survivors at particularly high risk for suicide. For example, Dr. Han and her colleagues explained, people treated for cancer during childhood are at increased risk of suicide through adulthood. This group is also at risk for other adverse mental health outcomes and may need close mental health follow-up over their lifetime.

And although advances in supportive care, as well as improvements in how long people are living after cancer treatment, have likely fueled the drop in cancer-related suicides, researchers would like to know more about which services provide the greatest reduction in risk and where people are falling through the cracks.

Dr. Han and her team are currently following a large group of patients during and after cancer treatment to look at these questions. Such research is needed “to understand where more improvements are needed, and [how to] ensure equitable access to these services as well,” she concluded.