, by NCI Staff

An inherited condition called neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is linked to the development of more types of cancer than previously realized, according to results from a new study. People with NF1 also have a greater chance of dying from some cancer types than people without the condition, the study found. These include some rare types of sarcoma, as well as ovarian cancer and melanoma.

The hallmark of NF1 is the development of neurofibromas, which are tumors that develop from the cells and tissues that cover nerves. While neurofibromas are usually benign—that is, they tend not to spread to other places in the body—they can cause serious health problems as they grow, including pain and damage to surrounding tissues.

People with NF1 are also known to have a higher risk of cancerous tumors, including a sarcoma called malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST), brain cancer, and breast cancer, than people without the condition. Researchers have estimated that such malignant cancers decrease the life expectancy of people with NF1 by an average of 10 to 15 years. But because NF1 itself is relatively rare, researchers have struggled to assemble a comprehensive picture of these cancer risks.

“We’ve known that people with NF1 are at a greater risk of developing certain cancers, and that they have a genetic predisposition to developing these cancers earlier [in life],” said Brigitte Widemann, M.D., chief of NCI’s Pediatric Oncology Branch, who was not involved with the study.

“This study shows that there are some other cancers that we didn’t know are associated with NF1, and also that the outcomes of these cancers may be worse” than in people without the condition, Dr. Widemann added. “This is important for patients to know.”

“These findings won’t change the way patients with NF1 are treated for any cancers they may develop, but they emphasize the importance of preventive measures and early diagnosis,” said Keila Torres, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, who led the research. “We strongly recommend that patients with a diagnosis of NF1 be referred to a neurofibromatosis specialist or neurologist” who would know about their increased cancer risk, she added.

Results from the new study, which was funded in part by NCI, were published March 18 in JAMA Network Open.

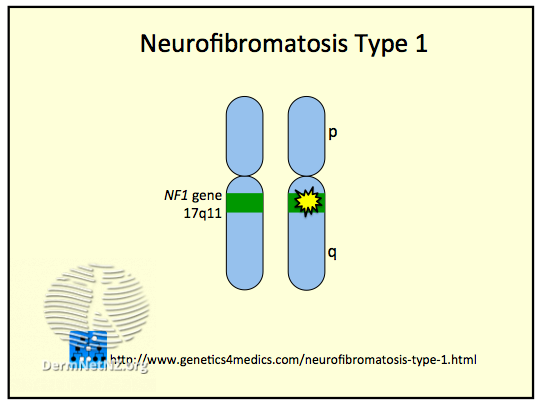

One Gene, Many Changes

NF1 is caused by inherited changes in the NF1 gene, which provides instructions for making a protein called neurofibromin. The symptoms and the course of NF1 can vary widely. Most people with NF1 are diagnosed within their first few years of life, while others might not know they have the condition until they reach their 20s, 30s, or even later.

In addition to developing neurofibromas, people with NF1 often develop coffee-colored skin spots and benign skin tumors, freckling of the skin that is not exposed to the sun, and abnormalities in the bones and central nervous system.

Because NF1 is relatively rare—around 1 in 2,500 to 3,000 people are thought to be living with the condition—it is unlikely for any one hospital or clinic to come across more than a handful of individuals with NF1.

The size of MD Anderson provided an opportunity to analyze data from a large number of people with NF1 who have been treated there over more than 3 decades to provide a clearer picture of the link between NF1 and different cancer types.

More Cancers Associated with NF1 Than Previously Known

Dr. Torres and her colleagues collected data on about 1,600 people with NF1 treated at MD Anderson between 1985 and 2020. They compared cancer diagnoses and disease-specific survival for each cancer type in people with NF1 with estimates for the general population taken from NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program database.

The median age of those with NF1 at their first visit to MD Anderson was 19 years and ranged from 1 month to 83 years. Overall, people with NF1 were almost 10 times more likely to develop any type of cancer during their lifetime than the general population.

Some of the results from the new study were similar to those from previous studies. For example, about 40% of the people with NF1 developed tumors other than neurofibromas. The most common were glioma, a type of brain tumor, diagnosed in 295 patients (about 18%) and MPNST, a rare sarcoma, diagnosed in 243 (about 15%). One hundred sixteen people (about 7%) developed more than one type of cancer.

But several cancers found to be associated with NF1 hadn’t been identified in previous studies. These included several rare sarcomas, neuroendocrine tumors, ovarian cancer, and melanoma.

People with NF1 also developed some cancers at an earlier age and were more likely to die from several cancer types compared with the general population. For example, about 33% of people with NF1 who developed melanoma died from that cancer within 5 years of diagnosis, compared with 8% of people diagnosed with melanoma in the general population.

|

Cancers that are more common in people with NF1 |

Cancers occurring at a younger age in people with NF1 |

Cancers that appear to be more deadly in people with NF1 |

|

|

|

|

It’s not known what could be driving worse survival for some cancer types in people with NF1. It may be that people with NF1 receive their cancer diagnosis at a later stage compared to people without NF1, when it is harder to treat, Dr. Widemann explained, or it may also be that treatments are less effective due to different molecular causes of cancer in people with NF1.

If You Feel Something, Say Something

The study “confirms previous notions about cancer in patients with NF1,” wrote Thierry Alcindor, M.D., of McGill University, in an accompanying editorial. It also shows that the number of associated cancers “is broader than previously suspected and that the outcomes of these cancers are worse than those in the general population.”

The poorer prognosis for many cancer types among people with the condition “should trigger special vigilance from clinicians caring for patients with NF1,” Dr. Alcindor added.

Some specialized cancer screening guidelines already exist for people with NF1. For example, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends that women with NF1 start breast cancer screening at age 30 rather than at age 40 for women at average risk. But for most of the cancer types associated with NF1, early detection methods don’t currently exist, explained Dr. Widemann. This makes it especially important for people not to dismiss any new symptoms, she said.

“Many people deal with pain and other problems from their NF1, and I think they’re more prone sometimes to just ignore [it] when something new happens,” said Dr. Widemann. “They may have a new pain, but they always have pain. So I would very much counsel them that, when something changes or there are new symptoms such as pain, to see a doctor early.”

“Patients with neurofibromatosis should see their doctor as soon as possible if they notice any lumps, rapid growths, or pain,” agreed Dr. Torres. They also need rigorous yearly evaluations by a specialist to check for signs of cancer and other complications of NF1, including abnormalities in their blood pressure, skin, nervous system, eyes, spine, and limbs, she added.

“The reason for these annual checks is to detect these cancers early, when more treatment options are available,” Dr. Torres said.

More work is needed to learn whether some types of cancer should be treated differently in people with NF1. Research has already shown that several tumor types in people with NF1, such as a type of sarcoma called gastrointestinal stromal tumor, have a different molecular driver than those that arise in the general population, Dr. Widemann explained.

Such efforts are hampered by NF1’s rarity, but projects are underway to expand the number of people participating in clinical trials, said Dr. Widemann. For example, the Children’s Tumor Foundation has started a registry where people with NF1 can record their interest in joining future studies.

She also recommends that, whenever possible, people with NF1 get their care at a specialty NF1 clinic. “That means [being seen by] a multidisciplinary group that really knows these cancer risks and will evaluate the patient appropriately,” Dr. Widemann said. “Not every doctor has the needed knowledge of NF1.”

If a specialty clinic isn’t available, people with NF1 would benefit from a referral to a health care provider who has experience with the condition, explained Dr. Torres. Specialty care can make a difference for everything from genetic testing for family members to cancer care, she added.

“These cancers are aggressive, and the order and types of treatment used … can determine a patient’s outcome,” she said. “It’s essential for patients with NF1 who develop cancer to discuss all the treatment options [with a specialist] and, if possible, get a second opinion.”