The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has recommended zanubrutinib (Brukinsa) as an option for treating some people with Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinaemia (WM), a rare type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) that develops in white blood cells.

Zanubrutinib is now the first WM drug NICE has recommended for routine NHS use in England. It is likely that the decision will also apply to Wales and Northern Ireland.

After comparing zanubrutinib to the main treatments currently used by NHS England, the NICE committee concluded that it was clinically effective and may help people with WM live longer and have a better quality of life

In making its decision, the committee called the routine use of zanubrutinib a “step-change” in managing WM.

Kruti Shrotri, Head of Policy Development at Cancer Research UK, said: “This decision is good news for people affected by Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinaemia. Current treatment options include chemotherapy and immunotherapy, but these can severely impact people’s quality of life. Patients told NICE they would therefore value more treatment options.”

A different approach to Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinaemia

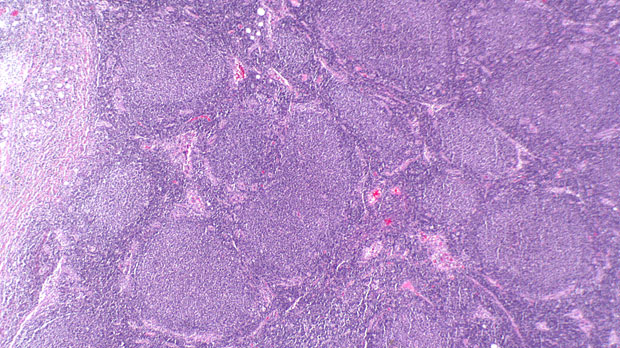

WM (sometimes called lymphoplasmacytic NHL) is an incurable type of low grade NHL. ‘Low grade’ means it grows slowly.

These low grade lymphomas usually affect a type of white blood cell called B cells, which, when healthy, create antibodies that help the immune system fight viruses and bacteria. In WM, abnormal B cells fill up the bone marrow or enlarge the lymph nodes or spleen.

Zanubrutinib is designed to interrupt this process by blocking an enzyme called Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK).

BTK helps B cells, including the cancerous ones in people with WM, grow and survive, so targeting it can stop the cancer from growing.

This is different from the 2 primary treatments currently available on the NHS in England, which kill cancer cells directly or guide the immune system to do so.

Considering the evidence

NICE recommended zanubrutinib after considering the findings of the ASPEN study, a randomised phase 3 clinical trial that compared zanubrutinib with ibrutinib (Imbruvica), an older kinase inhibitor used routinely by the NHS in Scotland.

Those results showed that 28% of people with WM treated with zanubrutinib (29 out of 102) had almost no signs of cancer after 20 months of treatment. This was more than the 19% of people treated with ibrutinib (19 out of 99), but not by enough to be statistically significant.

Nonetheless, the study found that “zanubrutinib treatment was associated with a trend toward better response quality and less toxicity”.

As ibrutinib is not approved by NICE for the treatment of WM, the ASPEN findings were indirectly compared with the results of 2 separate studies. These evaluated the combinations of chemotherapy and immunotherapy most often used by the NHS in England: bendamustine plus rituximab (BR), and dexamethasone plus rituximab and cyclophosphamide (DRC).

Conclusive information on how effectively zanubrutinib can help people with WM over the long term was not available at the time of the decision. Even so, the committee agreed that people with WM may live longer and have a better quality of life with zanubrutinib than with BR or DRC.

The potential for improved quality of life

One of the key reasons for improved quality of life is that zanubrutinib is a pill that people can take without going to the hospital for infusions. It also tends to cause less debilitating side effects than chemoimmunotherapy.

A patient expert who spoke to the NICE committee explained that, after significant issues with chemoimmunotherapy, zanubrutinib had enabled him to return to the activities he enjoyed before his WM diagnosis.

NICE recommends that the drug should now be a treatment option for people with WM who have had at least 1 previous therapy and are also suitable for treatment with BR.

The Welsh government has directed the NHS in Wales to make medicines available within 2 months of NICE recommendations. As such, an estimated 300 people with WM across England and Wales should soon be eligible to receive zanubrutinib.

NICE decisions are also usually adopted in Northern Ireland. The Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC), which fulfils a similar role to NICE for the NHS in Scotland, recently decided not to recommend zanubrutinib for use there, concluding that the drug’s potential health benefits were outweighed by its costs.