As part of our partnership with ScottishPower, our chief clinician headed to the world’s most important climate change conference to talk about the links between pollution and lung cancer in never smokers. There is definite shift in how we think about the disease says Professor Charles Swanton, but we have a long way to go. Here we chat with him and his lab on what we know, what we need to know and how we’ll get there…

In-person scientific conferences, it’s fair to say, have been thin on the ground over the past two years. And, as Cancer Research UK’s chief clinician, Professor Charles Swanton was eager to get them back in his diary.

It came as something of a surprise, then, when his first in all that time wasn’t exactly what he imagined.

“Who would have guessed that my first meeting in over 18 months would be a climate change conference!” He says. “But that really is a reflection of how important this is.”

The event was one of the many satellite meetings that took place during the recent UN Climate Change Conference, COP26, and was an opportunity brought to CRUK by our longstanding corporate partner in the renewable energy sector, ScottishPower, who were a Principal Partner of the summit. So, why was it so important that Swanton speak to the great and the good of environmental science as they gathered in Glasgow?

The answer lay in the growing number of lung cancer cases in patients who have never smoked.

“We’ve got a situation where lung cancer in never smokers is a significant proportion of lung cancer cases. I’d estimate we’re probably talking about 3,000-6,000 deaths a year in the UK,” says Swanton. “So that that’s equivalent to melanoma or renal cancer. It’s a lot of deaths.”

Indeed, if lung cancer in never smokers were considered a separate disease, it would be the eighth most prevalent cause of cancer death in the UK. While it’s not yet fully clear if this increase simply reflects increasing numbers of people who have never smoked combined with an ageing population, what is known well is the association between lung cancer and pollution. As such, Swanton, who is co-director of the Cancer Research UK Lung Cancer Centre of Excellence, found himself eager to be speaking at the Air Pollution and Cancer event hosted by ScottishPower.

Moving beyond an association

Outside of smoking tobacco, exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and workplace carcinogens are the two most important risk factors for lung cancer. However, a history of either is absent in more than a third of lung cancer cases in never smokers.

“These are never smokers without any obvious risk factors,” says Swanton. “And the key question is, what is driving this?” Various causes have been suggested including germline risk, radon exposure, and even exposure to hot cooking oils. “But, it’s air pollution that me and my lab are most interested in,” he says.

And when you examine the numbers behind never smoker lung cancer it’s clear to see why it’s becoming a greater focus for Swanton and his lab. In 2017 a US study looking at 12,103 lung cancer patients from three hospitals concluded that from 1990–95, 8% of those patients were never smokers. From 2011–13, partly because of a reduction in smoking associated lung cancers, that rose to 14.9%.

Another study from 2017, this time based in the UK, showed an equally worrying trend. After studying 2,170 lung cancer patients from 2008 to 2014, it suggests the annual frequency of developing lung cancer in never smokers more than doubles from 13% to 28%.

A complete understanding of why is yet to be grasped, but the link between particulate air pollution and lung cancer is not a new one. However, says Dr Emilia Lim – a bioinformatician working on never smoker lung cancer in Swanton’s lab – recognising an association is not enough. “It’s been long known that air pollution is associated with lung cancer, people have been studying this for many years,” she says. “We now need to describe how this actually happens.”

It was back in 2013 that the WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), announced it was classifying air pollution as a class 1 carcinogen. That was an important moment, but there was – and still is – a lack of biological understanding says Dr William Hill, a postdoctoral researcher in Swanton’s lab. “If you read the IARC report, it’s largely based on epidemiological data. And there has been some fantastic epidemiological studies looking at the association of pollution and lung cancer,” he says. “But we need to improve our understanding and really see if we can find the biology behind this.”

And that need is a pressing one says Swanton. “People across the globe are exposed daily to toxic pollutants that get right to the distal areas of the lung and, for reasons we don’t understand, cause cancer. Many have no choice – they have to work, and they have to live in polluted cities.”

Dr William Hill and Dr Emilia Lim at the recent UN Climate Change Conference, COP26

This message certainly found a receptive audience at the ScottishPower event. “We have an absolute commitment to renewable power generation” says Andrew Ward, ScottishPower’s CEO of UK Retail. “As one of the Principal Partners for COP26, we have been able to support CRUK in highlighting that our aim of helping the world decarbonize is also key to achieving the goal of reducing cancers related to air pollution.”

Separate entity

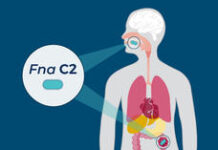

So what, exactly, are these toxic pollutants?

Largely they are the fine particulate matter that result from combustion – be that burning fuel for transport or energy production. Submicron combustion-related particulate matter under 2.5µm in diameter, known as PM2.5, is of particular concern. It can penetrate deeper into the lung than the larger particles generated by natural processes – such as pollen, sand and soil – and is thought to have caused around 265,000 (14%) of global lung cancer deaths in 2017.

“These particulates are a likely key cause of lung cancer in never smokers,” says Swanton. So, is it time to start thinking of never smoker lung cancer as a completely separate disease?

Despite a less than clear picture of the problem, says Lim, there are compelling reasons to do so. “For lung cancer, because most of the emphasis has been on smoking as a cause, we don’t actually know as much about the disease in never smokers,” she says. “What we do know is that it occurs more frequently in women and in Asian people.”

The differences continue at the histological level as well. Squamous carcinomas are highly enriched in smoking associated lung cancer, whereas it’s adenocarcinomas which dominate in never smokers.

There’s variation, too, in the genomics – it’s quite distinct from smoking related lung cancer, says Lim. “There’s a very specific mutational signature that you can attribute to tobacco smoke, but this doesn’t exist in never smokers. So, this is the puzzle that we’re trying to solve here. What we do know is that one gene is frequently mutated in these never smoke lung cancers – the EGFR gene.”

There is also impetus to see this as a separate disease from a clinical perspective. “As fewer people smoke, relatively more cases will be diagnosed in people who have never smoked,” says Swanton. “It’s becoming a much more obvious problem in clinical practice than it was before. We really need more research in this area.”

While the decline in smoking might have only relatively recently revealed never smoker lung cancer as clinically important, there is another reason for the lack of research interest says Hill.

“For lung cancer in general, smoking is the overwhelming risk factor and so for quite a while a lot of research focused on this,” he says. “Lung cancer in never smokers has been a bit of an orphan disease where there is a sort of implicit assumption that lung cancer is a disease brought about by smoking only. That is really changing now.”

An enigmatic disease

As attitudes to never smoker lung cancer change, interest grows in researching the field. Which is clearly a good thing – not only for patients, but also for the scientists taking on the challenge.

“This really is an important problem,” says Swanton. “It’s a very enigmatic disease, that we really have only just begun to understand – there is simply so much for researchers to unpick.”

Not least of which is the very relationship between carcinogens and cancer itself. While there is a clear link between mutation of the EGFR gene and never smoker lung cancer, it’s also the case that compared to many other cancer types – including smoking associated lung cancer – there is a very low mutation rate seen in the disease. So, if not mutation, then how are these environmental particulates causing lung cancer?

It’s exactly this problem that Swanton’s lab is focusing on. “What’s really interesting to me about our recent never smoker lung cancer work is that it could change the way in which we understand how risk factors promote disease,” says Lim.

Early results – largely thanks to Swanton’s work with the TRACERx study – are beginning to paint a picture of how PM2.5 might combine with EGFR mutations to drive lung cancer.

At the moment we simply don’t know the biological mechanism that links air pollution and lung cancer. Something that won’t be helped, thinks Swanton, by entrenched ideas. “To some extent, I think we have been misled by the thinking that all carcinogens cause mutations. We now think it is a lot more complicated than that and so the message is, this is a research field of unmet need. This is an area that deserves more investment and more thought.”

And so, future work on never smoker lung cancer could not only change the way we think about and treat the disease, impacting thousands of patients in the UK alone, but it could also change the very fundamentals of how we think about the relationship between carcinogens and cancer.

ScottishPower and Cancer Research UK, working together for a greener, healthier future

Cancer Research UK’s partnership with ScottishPower began in 2012 and since then it’s raised over £30m. We recently announced that we’re extending this extraordinary partnership for another three years. As ScottishPower now generates only renewable energy, our partnership reflects our shared interest in a greener, healthier future.

Professor Charles Swanton is a clinician scientist, focusing his work on understanding the challenges inherent in the management of metastatic cancer and their drug resistant and incurable nature. He was appointed CRUK senior clinical research fellow in 2008. Charles is the chief investigator of the CRUK TRACERx clinical study to decipher lung cancer evolution and is co-director of the CRUK Lung Cancer Centre of Excellence.

Professor Charles Swanton is a clinician scientist, focusing his work on understanding the challenges inherent in the management of metastatic cancer and their drug resistant and incurable nature. He was appointed CRUK senior clinical research fellow in 2008. Charles is the chief investigator of the CRUK TRACERx clinical study to decipher lung cancer evolution and is co-director of the CRUK Lung Cancer Centre of Excellence.

Dr Emilia Lim is a post-doctoral research fellow in the Cancer Evolution and Genome Instability Laboratory at the Francis Crick Research Institute, where she is a bioinformatician on the TRACERx project.

Dr Emilia Lim is a post-doctoral research fellow in the Cancer Evolution and Genome Instability Laboratory at the Francis Crick Research Institute, where she is a bioinformatician on the TRACERx project.

Dr William Hill joined Professor Charles Swanton’s group in 2019. He is developing novel evolutionary preclinical models of lung cancer that better mimic what is observed in the clinic. This will improve our understanding of tumour evolution trajectories and intratumour heterogeneity.

Dr William Hill joined Professor Charles Swanton’s group in 2019. He is developing novel evolutionary preclinical models of lung cancer that better mimic what is observed in the clinic. This will improve our understanding of tumour evolution trajectories and intratumour heterogeneity.