, by NCI Staff

A type of radiation treatment called proton beam radiation therapy may be safer and just as effective as traditional radiation therapy for adults with advanced cancer. That finding comes from a study that used existing patient data to compare the two types of radiation.

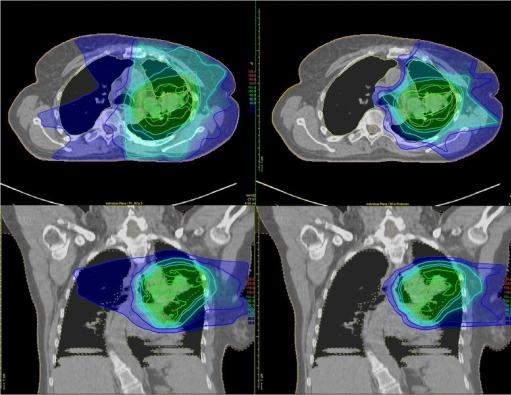

Traditional radiation delivers x-rays, or beams of photons, to the tumor and beyond it. This can damage nearby healthy tissues and can cause significant side effects.

By contrast, proton therapy delivers a beam of proton particles that stops at the tumor, so it’s less likely to damage nearby healthy tissues. Some experts believe that proton therapy is safer than traditional radiation, but there is limited research comparing the two treatments.

Plus, proton therapy is more expensive than traditional radiation, and not all insurance companies cover the cost of the treatment, given the limited evidence of its benefits. Nevertheless, 31 hospitals across the country have spent millions of dollars building proton therapy centers, and many advertise the potential, but unproven, advantages of the treatment.

In the new study, patients treated with proton therapy were much less likely to experience severe side effects than patients treated with traditional radiation therapy. There was no difference in how long the patients lived, however. The results were published December 26 in JAMA Oncology.

“These results support the whole rationale for proton therapy,” said the study’s lead investigator, Brian Baumann, M.D., of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the University of Pennsylvania.

But key aspects of the study limit how broadly the findings can be interpreted, said Jeffrey Buchsbaum, M.D., Ph.D., of NCI’s Radiation Research Program, who was not involved in the study.

Because of those limitations, “the evidence needed to truly justify the expenses of proton therapy … will need to come from phase 3 randomized clinical trials,” wrote Henry Park, M.D., and James Yu, M.D., of Yale School of Medicine, in an accompanying editorial.

Several NCI-funded randomized clinical trials comparing proton and traditional radiation therapy are currently ongoing. (See the box below.)

Safety and Efficacy of Proton Therapy

Many people with locally advanced cancers are treated with a combination of chemotherapy and either traditional or proton radiation. For patients getting chemotherapy and radiation at the same time, finding ways to limit side effects without making the treatment less effective is a high priority, Dr. Baumann said.

He and his colleagues analyzed data from nearly 1,500 adults with 11 different types of cancer. All participants had received simultaneous chemotherapy plus radiation at the University of Pennsylvania Health System between 2011 and 2016 and had been followed to track side effects and cancer outcomes, including survival. Almost 400 had received proton therapy and the rest received traditional radiation.

Those who received proton therapy experienced far fewer serious side effects than those who received traditional radiation, the researchers found. Within 90 days of starting treatment, 45 patients (12%) in the proton therapy group and 301 patients (28%) in the traditional radiation group experienced a severe side effect—that is, an effect severe enough to warrant hospitalization.

In addition, proton therapy didn’t affect people’s abilities to perform routine activities like housework as much as traditional radiation. Over the course of treatment, performance status scores were half as likely to decline for patients treated with proton therapy as for those who received traditional radiation.

And proton therapy appeared to work as well as traditional radiation therapy to treat cancer and preserve life. After 3 years, 46% of patients in the proton therapy group and 49% of those in the traditional radiation therapy group were cancer free. Fifty-six percent of people who received proton therapy and 58% of those who received traditional radiation were still alive after 3 years.

Limitations of the Study’s Design

The study leaders and other experts noted several limitations to the study’s design.

For instance, this observational study can’t establish a cause-and-effect relationship between proton therapy and fewer side effects. In addition, all of the study participants were treated at a single institution, which can make it difficult to generalize the findings to a larger population.

“Those are very significant limitations that shouldn’t be understated,” Dr. Buchsbaum emphasized.

Although single-institution studies have inherent limitations, Dr. Baumann noted, all patients in this study received high-quality treatment at a large academic medical center, regardless of whether it was proton or traditional radiation therapy, “which suggests that the benefit of proton therapy that we saw is meaningful.”

Also, because patients were not randomly assigned to treatment groups, there were differences between patients who got proton and traditional radiation, and that may have skewed the results.

For instance, patients who received proton therapy were, on average, older (likely because Medicare typically covers the cost of proton therapy) and had more health issues.

The proton therapy group may also have included more patients from “privileged backgrounds,” Drs. Park and Yu noted. Socioeconomic status and social support can affect treatment outcomes, they wrote.

In addition, fewer people with head and neck cancer—who are more likely to suffer from radiation-associated side effects—were included in the proton therapy group, the editorialists added.

In their analysis, the investigators used complex statistical techniques to try to account for these differences as much as possible.

Ideas for Future Studies of Proton Therapy

Despite the study’s limitations, these “intriguing findings raise questions that should inform future prospective phase 3 trials,” Dr. Buchsbaum said, although there are barriers to large studies of proton therapy.

For instance, it “is particularly encouraging” that proton therapy appeared to be safer in a group of older and sicker patients who typically experience more side effects, Dr. Baumann noted.

Dr. Buchsbaum agreed that proton therapy may be especially helpful for older and sicker patients, but he noted that ongoing phase 3 trials were not designed to analyze this group of patients.

And because proton therapy may cause fewer side effects, future trials could also explore whether combining proton therapy with chemotherapy might be more tolerable for patients, the authors wrote.

For example, both chemotherapy and traditional radiation for lung cancer can irritate the esophagus, making it painful and difficult for patients to eat. But proton therapy might limit damage to the esophagus, making it easier for a patient to tolerate the combination, Dr. Baumann explained.

Future studies could also explore whether combining proton therapy with higher doses of chemotherapy might increase cures without causing more side effects, he added.

The study findings also raise “the tantalizing possibility that the higher up-front cost of proton therapy may be offset by cost savings from reduced hospitalizations and enhanced productivity from patients and caregivers,” the study researchers wrote.

Dr. Buchsbaum agreed, saying that it would be worthwhile to explore this possibility. “Just asking the question: ‘Is [proton therapy] more effective?’ might not be giving it a fair opportunity to demonstrate its benefit to society,” he said.

Dr. Baumann and his colleagues are currently studying the cost effectiveness of proton therapy, considering aspects like the costs of treating side effects and the value of preserved quality of life.