When we think about cancers, and specifically treating cancers, we tend to think about targeting tumour cells directly with chemo- or radiotherapies.

However, what makes targeting tumour cells even more complicated is that tumours don’t exist in isolation. They are surrounded by what’s called the tumour microenvironment.

The tumour microenvironment is a kind of ecosystem around a tumour, made up of blood vessels, immune cells, enzymes and a variety of other cells the tumour needs to survive, including cells called fibroblasts that are essential in building connective tissue.

A tumour is constantly interacting with its microenvironment, and research suggests that this microenvironment is key to a cancer’s development.

To put it into context, if you think of a tumour as a plant, the microenvironment is its soil, allowing it to grow and spread more quickly.

Now, researchers have found a drug that targets the tumour microenvironment that could improve treatment for certain cancers. But it might not be the kind of drug you expect.

Finding a new target

In some cancers, the tumour microenvironment allows tumours to resist treatment, preventing chemotherapy from having a beneficial effect.

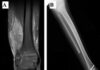

This is the case in oesophageal cancer, cancer that affects the food pipe that connects your mouth to your stomach, which, though rare, currently has poor survival outcomes.

To try to overcome this resistance, a team of researchers funded by us and the Medical Research Council, led by Professor Tim Underwood at the University of Southampton, wanted to identify the cells in the tumour microenvironment that protect the tumour from treatment so they could target them.

“Where targeting cancer cells with one specific treatment can be difficult because they differ between patients, targeting the microenvironment cells may be more likely to have traction because they are similar across patients,” says Underwood, a professor of gastrointestinal surgery.

“Rather than going after the cancer cells, actually, if we take away their ‘soil’ and go after the environment they live in, we might have more success.

“The plants might be different, but if you poison the soil, they’ll all die.”

New uses for old drugs

By examining cells from oesophageal cancers called adenocarcinomas, the team found that levels of an enzyme called PDE5 are higher in these cancer cells than in health oesophageal tissues.

Specifically, the high levels of PDE5 were found in cells called cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs), which are important for tumour growth. They also found that the more PDE5 a tumour contained, the worse the prognosis was, suggesting that PDE5 would be an effective target for treatment.

Luckily, drugs that inhibit the PDE5 enzyme already exist, and whilst the name might sound unfamiliar, there’s one PDE5 inhibitor in particular you’ve probably heard of before.

Drugs like Viagra, used to treat erectile dysfunction, are PDE5 inhibitors.

The researchers discovered that in addition to its usual function of relaxing muscles to allow increased blood flow, PDE5 inhibitors were able to suppress CAF activity, and make them behave like normal fibroblasts again.

Improving treatment safely

Once Underwood’s team had found that PDE5 inhibitors worked, they moved on to the next stage with collaborating researchers at the University of Nottingham.

This team took samples of tumour cells from 15 tissue biopsies from 8 patients and used them to create artificial lab-grown tumours. With these tumours, the researchers could test a combination of PDE5 inhibitions and standard chemotherapy in the lab.

12 of these samples were taken from people whose tumours had shown a poor response to chemotherapy in the clinic. Of these, 9 were made sensitive to chemotherapy following the addition of the PDE5 inhibitor targeting CAFs.

They also tested the treatment on mice implanted with chemotherapy resistant oesophageal tumours and found that there were no adverse side effects to the treatment, and that chemotherapy combined with PDE5 inhibitors shrunk the tumours more than chemotherapy alone.

The benefit of repurposing existing drugs like PDE5 inhibitors is that they’re already proven to be safe and well-tolerated in thousands of patients worldwide, even in the higher doses that would be required for this kind of treatment.

But just to clarify if you’re wondering, the researchers say that giving PDE5 inhibitors to people with oesophageal cancer would be extremely unlikely to cause erections without the appropriate stimulation.

“The chemotherapy resistant properties of oesophageal tumours mean that many patients undergo intensive chemotherapy that won’t work for them,” says Underwood.

“Finding a drug, which is already safely prescribed to people every day, could be a great step forward in tackling this hard-to-treat disease.”

with his son at a Race for Life event</p>

<p> ” data-medium-file=”https://news.cancerresearchuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Terry.jpg” data-large-file=”https://news.cancerresearchuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Terry.jpg” class=” size-full wp-image-24379″ src=”https://34p2k13bwwzx12bgy13rwq8p-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Terry.jpg” alt=”Terry Daly (right) with his son at a Race for Life event” width=”200″ height=”200″ srcset=”https://34p2k13bwwzx12bgy13rwq8p-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Terry.jpg 200w, https://34p2k13bwwzx12bgy13rwq8p-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Terry-150×150.jpg 150w, https://34p2k13bwwzx12bgy13rwq8p-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Terry-96×96.jpg 96w” sizes=”(max-width: 200px) 100vw, 200px”></p>

<p class=) Terry Daly (right) with his son at a Race for Life event

Terry Daly (right) with his son at a Race for Life event

Terry’s story

The new research has been welcomed by Terry Daly, 60 from Aldershot who was diagnosed with oesophageal cancer last October.

Terry said: “I’d been having difficulty swallowing and digesting food for about six months but put it down to indigestion. After a particularly bad incident, I went to the GP who referred me to the hospital where they performed an endoscopy. I knew by the look on the doctor’s face when he was doing the procedure that it wasn’t good news.

“I didn’t tell my wife, Donna, that I thought it was cancer at that point because I worried that she wouldn’t cope. She did come with me to the appointment though when they confirmed that it was cancer.

“It was a shock but my initial reaction was, ‘It is what it is’ and I have always tried to be positive because I believe I can beat this.

“I had chemo to try to shrink the tumour but it only reduced in size by a small amount. Then in April, I had an operation to take the tumour out and to stretch my stomach up to the remaining oesophagus.

“On day eight, my doctor couldn’t believe how well I was recovering but that night I became critically ill. They put me in an induced coma and took me back to surgery because the junction hadn’t taken and they needed to repair it urgently. I was in and out of surgery for several days and spent two weeks in intensive care.

“Now I’ve recovered from the surgery and have just started chemo again followed by radiotherapy.

“I think the new research is brilliant news and perhaps if the drugs had been available alongside my first chemo, it could have shrunk my tumour more before my operation and made that whole process a lot better.

“It’s really reassuring to know that there are people trying to find out so much about this type of cancer and discover better treatments. They’re working tirelessly to make people’s lives better and to help them beat this.

“My son did the Race for Life and raised £3,500 to fund research like this and I couldn’t be prouder. Next year I want to do the Race for Life with him and that’s my goal. It will also be mine and Donna’s 40th wedding anniversary. She is my rock and I want to make sure I am around for her and for my grandchildren.”

Hope for future research

Though oesophageal cancer is rare, the UK has one of the highest rates in the world, with over 9,000 new cases diagnosed every year.

On top of that, oesophageal cancer currently has much poorer outcomes and treatment options compared to other cancers, with around just 1 in 10 patients surviving their disease for 10 years or more.

The resistance to chemotherapy that the tumour’s microenvironment provides to these cancers is a large contributing factor to these poor outcomes, with around 80% of people not responding to the treatment.

Although this is early discovery research, PDE5 inhibitors combined with chemotherapy may be able to shrink some oesophageal tumours more than chemotherapy could alone, tackling chemotherapy resistance, which is one of the major challenges in treating oesophageal cancer.

If further trials are successful, this treatment could help people diagnosed with oesophageal cancer within the next 5 to 10 years.

Jacob